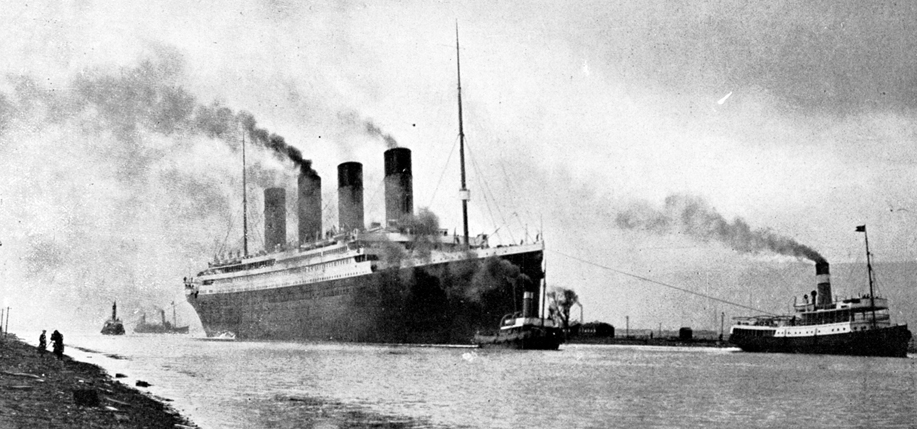

This week marks the 104th anniversary of the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic in the early morning hours of April 15, 1912. With the ship’s final port in Europe in Cobh, Ireland (then called Queenstown,) one does not have to dive too far into the story of the R.M.S. Titanic to find Irish connections.

The ship was designed and built by the Belfast industrial company, Harland and Wolff, and today both Belfast and Cobh are now home to popular museums devoted to the “unsinkable” luxury liner. On board, too, a large number of Titanic passengers were born in Ireland, especially in third class, and much of the crew.

One of the Titanic’s most famous real-life passengers was philanthropist and activist Margaret “Molly” Brown, a first-generation Irish American, born in Hannibal, Missouri to John and Johanna (née Collins) Tobin in 1867. Unlike all of the Titanic’s other famous passengers, however, it was Brown’s actions during the ship’s sinking that cemented her renown, despite having been a vociferous advocate for laborer’s and women’s rights before April of 1912.

Now known as the “Unsinkable Molly Brown” (later the title of a film and a stage musical based on her life), she reportedly led a group of women in commandeering their lifeboat from Quartermaster Robert Hitchens and attempting to return to the wreckage to search for survivors. Like many other legends surrounding the Titanic’s sinking, the story may be an apocryphal one, but Brown’s documented heroism – while perhaps not the stuff of film scripts – made a huge impact. While on board the Carpathia, the ship that rescued the Titanic survivors early the following morning, she organized and chaired the Survivor’s Committee, which raised nearly $10,000 for impoverished survivors of the wreck before even landing in New York.

Many are familiar with the now-famous photographs offering glimpses of life on board the Titanic. The man who snapped them, however, is less well known. Jesuit Fr. Francis Browne was born in Cork in 1880, and following the deaths of his parents, he was raised by his uncle, the Bishop of Cloyne, who encouraged his love of travel and photography. His uncle presented him with not only his first camera, but a first-class ticket from Southampton to Queenstown on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. Both gifts, it seemed, would be instrumental to the legacy of the man that fellow photographer David Davidson later deemed an Irish Cartier-Bresson.

Browne boarded the ship in Southampton (he and the ship’s designer, Belfast-born Thomas Andrews, were among a very small number of Irish among the first class passengers) and befriended a millionaire American couple who offered to pay for his passage from Queenstown to New York in return for his company on the voyage. When Browne telegraphed his superior for permission to undertake the journey, the response from Dublin was direct and ultimately life-saving: “GET OFF THAT SHIP.” He kept a copy of the telegram in his wallet until his death in 1960.

Once news of the tragedy reached him, he realized the numerous photographs he took while on board would be of major interest, and began negotiating sales with various news outlets. Though Browne spent only two days aboard the liner, the photographs he took are the best surviving record of life on the Titanic at sea.

Former New York City City Council Speaker Christine Quinn’s Irish grandmother was a Titanic survivor, one of the few third-class passengers to be rescued. Ellen Shine Callaghan boarded the Titanic when she was in her late teens (the exact age is unknown) in Queenstown, Co. Cork. According to the New York Times, “Nellie Shine had been living in rural Ireland near Newmarket, County Cork, with an elder sister after their parents died. They took in an orphaned infant, making the household crowded, and it was quickly decided that Nellie would clear out and go to America. As it happened, the Titanic’s last port of call was Queenstown, known today as Cobh, about 50 miles from home.”

For more information, Encyclopedia Titanica, which began in 1996, is the most successful attempt at documenting the story of every person – passenger and crew – aboard the Titanic. Their data comes mainly from the ship’s manifests, birth and death records, and interviews or anecdotes from fellow passengers and family. One can even search for passengers and crew by their home country and learn how many Irish-born counted among the 712 survivors and 1496 victims of the disaster. The “home country” list classifies those on board by their listed address, so the majority of the ship’s crew are listed as being from England, despite having been born in Ireland or elsewhere, however. ♦

Leave a Reply