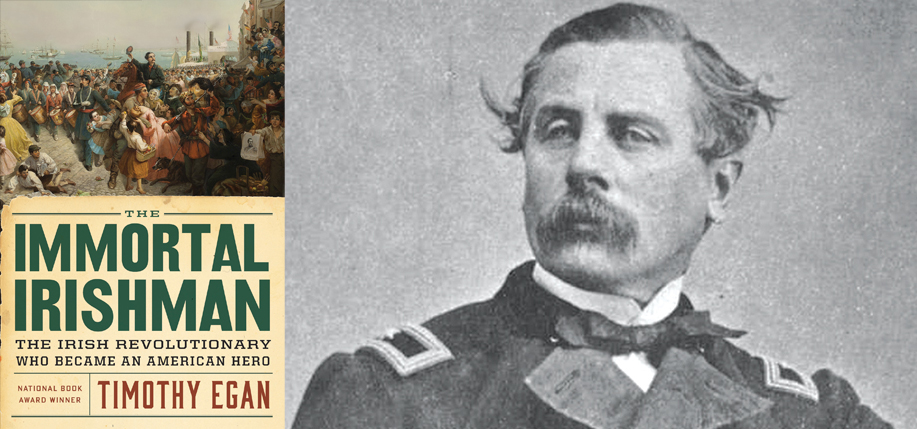

In the following excerpt from Timothy Egan’s new book on Thomas Meagher, the legendary Irishman arrives in New York City having escaped from the Tasmanian prison colony where he had been banished for his part in the failed 1848 rebellion.

He had seen half the world from a ship’s deck, and yet nothing prepared him for how many of the earth’s uprooted strivers had stuffed themselves into New York City in 1852. Carriages dashed and shifted, horses clopped and whinnied, stevedores grunted and cursed, all in waves – not the music of commerce, but the off-key chorus of chaos. Boatmen, ferrymen, porters, carters, stage drivers, washerwomen, predators of immigrants, domestics walking other people’s children, and teenage girls in face paint handing out fliers for the afternoon melodrama on the Bowery. Was that the Teutonic tongue coming from Kleindeutschland, the third-largest German-speaking community in the world? And Yiddish rising from the cluster of rag merchants a few blocks in the other direction? What hybrid of the Queen’s English was this dialect of free blacks working dockside? Surely, a hint of County Kildare clattered from that street-cleaning crew, and his own Munster brogue rolled out of a basement shebeen. All of this in the kinetic claustrophobia of the Lower East Side, nursery of a nation whose people were looking less like those of the mother country by the day. Around one turn, the smells were unpleasant in the late-spring humidity, sweat twined with horseshit, dogshit and pigshit, the piles to be swept into the river by day’s end – 6,000 cartloads a night. A few blocks on, he was hit with a waft from the fresh-cooked offerings of barefoot girls, who enticed customers with this chant: “Hot corn! Here’s your nice hot corn! Smoking hot, smoking hot, just from the pot!” The island of Manhattan was smaller than the prison district where Thomas Meagher had been condemned to spend the rest of his life.

But it held a world of fellow exiles – from Russia’s pogrom-swept villages, from the Rhine’s ruined farms, from Africa’s plundered hamlets, and from ashen-blighted fields abandoned by those strong enough to walk away from the Great Hunger. On May 27, the day Meagher stepped ashore, this New York was home to just under 20,000 Jews, 12,000 African Americans, 60,000 Germans, and at least 160,000 Irish. It was the densest concentration of Irish anywhere: more than one in four New Yorkers in a city of nearly 600,000 had been born in Meagher’s homeland. He walked by City Hall, where men not long from Limerick or Kilkenny held actual power, up Broadway past the booksellers and portrait studios. Onward, toward Canal Street, then right in the direction of the Bowery. On alternate days, bare-knuckle boxing shared space with Shakespeare plays. A scattering of Irish soon became a thicket. They looked worn down and dirty-faced. Their tenements were awful – wooden gaols that could combust in a poof from an untended cigar. Here, flop joints, groggeries, and a row of slouch-roofed boardinghouses anchored a city block. The Bowery itself, once a footpath for the native Lenape, had the distinction of being the only major thoroughfare in New York City never to have a single church built on it. Nearby, a former brewery, converted from making beer to warehousing immigrants, was home to a thousand people, some living in stairwells and doorways. For 37 cents a week, you could sleep in a windowless room on a floor with straw; for 18 cents, just the bare floor, with a bucket for the latrine. Then, south to the center of this stew of start-over people – Five Points. He knew this neighborhood, five blocks in the heart of the Sixth Ward, by reputation. Charles Dickens had come through a few years earlier, notebook in hand, two cops by his side. The novelist was stunned to see the mix of races, Irish and blacks drinking together, dancing in the saloons, a born-in-America toe-and-heel tap that was a blend of Gaelic jig and West African step dance. In darkened corners, mixed-race couples kissed and groped. Where Anthony, Orange and Cross Streets came together, Dickens saw a place “loathsome, drooping and decayed.” No part of London could match the wretchedness of the neighborhood. It was without grass or trees, without a sliver of green. Thereafter, tourists paid armed men to guide them through an evening of slumming among the poor Irish – for a chance to be appalled at “shanties in which the pigs and the Patricks lie down together,” as the New York Times informed a readership accustomed to bedding in clean linen. The curious didn’t come to see the shoemakers and tailors, the fruit sellers and bricklayers. They came for what the great writer called “a world of vice and misery.”

℘℘℘

The Irish did not know it yet, on this last Thursday in May, that one of the most prominent of their political refugees walked among them – an escapee from Tasmania by way of South America. But he was expected. The Boston Pilot had reported in its May 15 edition that the Young Tribune was free. After changing ships in Brazil, from the Elizabeth Thompson to the American-flagged Acorn, he was due to arrive in the city any day, having been at sea for five months. The paper put the stamp of destiny on Meagher before he even saw New York Harbor. “In him, the Irish will find a chief to unite and guide them.” Ignorant of his future burden, Meagher thumbed through Doggett’s Directory in search of familiar names. For one day more, he was a stranger in a new land. Dublin’s loss, following the uprising of 1848, was New York’s gain. Young Ireland’s prominent plotters did not dwell in Five Points. They lived well, as barristers, publishers, journalists and politicians – power brokers many of them, still in their twenties. They joined the company of other Irish who had prospered in the city. Archbishop John Hughes, the son of poor farmers in County Tyrone, was the most influential cleric in the country, signing his letters to the editor, his church edicts and personal notes with his signature cross, which looked like a dagger. And so he was known as Dagger John. Another Tyrone man, Charles P. Daly, would soon be chief justice of the city’s common courts. The district attorney – the law in New York City – was John McKeon. “What he is,” a profile in the weekly Irish American exulted, “any of us might be.” In the Old World, the police were enforcers of a brutal system that kept the natives in their place. In the New World, they were heroic, and many spoke Gaelic. Half the cops in the Sixth Ward were Irish. Meagher’s destination on this day was 39 William Street, in a hive of silk-vested prosperity a few steps from Wall Street. Here were the law offices of Richard O’Gorman and John Blake Dillon – two great friends of Meagher’s, and two men who might have been hanged, drawn, and quartered had they not fled. Dillon, a cofounder of the Nation, had been with Meagher in the shadows during the last days of the uprising. After the Empire put a bounty on his head, he escaped to France and New York. A family friend and schoolboy chum from Clongowes Wood, O’Gorman had joined Meagher in Paris in 1848 for the ill-fated mission to enlist the help of a new French government. After the failure of the revolt, O’Gorman hid out in the wilds of County Clare for a month, the subject of a manhunt aided by a huge reward for his capture. Four years after the debacle in a Tipperary cabbage patch, both rebels were well-compensated, well-connected elites in the fastest-growing city in the world. When the partners greeted the man who walked into their office, they did a double take. The guest was stout, no longer boyish, his face the color of stained walnut. But when Meagher opened his mouth, all doubt dissipated – he was the same sparkler of a man they had known in Dublin, his declarative sentences delivered with customary snap and punch. They embraced and pinched each other’s cheeks as if they were ghosts brought to full-fleshed form. Many other Young Ireland coconspirators were building new lives in New York, Meagher’s mates informed him. Michael Corcoran was living above a tavern at 42 Prince Street. Corcoran had Ireland’s struggles in his blood: his great-great-great-great-grandfather was Patrick Sarsfield, defender of Galway and Limerick against William of Orange in the late seventeenth century. Born to a modest family in County Sligo, Corcoran joined the Royal Irish Constabulary at nineteen but didn’t last long as an enforcer of the Empire. The famine radicalized him. He became a double agent, working for the Crown by day, and undermining it by night. At last, he took off his badge and took up with Young Ireland. Corcoran, O’Gorman, Dillon, and Meagher – all outlaws in Ireland. Here, free men. And get this – we have the run of the city!

_______________

Excerpted from The Immortal Irishman by Timothy Egan. Copyright © 2016 by Timothy Egan. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Note: Following the First Battle of Bull Run, Meagher formed the Irish Brigade in New York and went on to become one of the Civil War’s most renowned generals. After the war he was appointed acting governor of the Montana Territory. He died in 1867 having fallen from a steamboat into the Missouri River. Some believe Meagher was murdered by his political enemies in Montana Territory.

This excerpt was published in the April / May 2016 issue of Irish America. ♦

Only the good Die Young sounds like a lot of fun wish i could have been there.

Great history! BUT, Africans Americans did not exist in the 1850’s. They are a political invention of the late 20th century.