With the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising upon us, a curious piece of memorabilia printed 150 years ago reminds us that the Rising was not the only bid for Irish independence. In the possession of Patrick Doherty, a director in the state comptroller’s office for New York, is a Fenian bond dating from 1866. Doherty is an avid collector of Irish artifacts and a well informed interpreter of their meaning and past. This bond, which he recently showed to Irish America, is only one of several such bonds in Doherty’s collection. It tells the story of the Fenian progenitors of 1916.

The tale begins following the calamities that befell Ireland as a result of the Great Famine, when multitudes of Irish immigrants came to the U.S. This migration coincided with the outbreak of the American Civil War, and many of these immigrants quickly enlisted in both the Union and Confederate Armies.

Some signed on simply to make a living, others did so to gain military expertise. The latter were men associated with an Irish revolutionary organization known as the Fenian Brotherhood, founded in the U.S. by John O’Mahony in 1848. The Fenians, also had a sister organization in Ireland called the Irish Revolutionary (later ‘Republican’) Brotherhood or IRB, a forbear of the IRA whose members were instrumental in staging the Easter Rising of 1916.

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, the Fenian veterans decided to move against the British through an invasion of Canada, which at that time was still a colony of the British empire.

But that operation needed to be financed, and so the Fenians started selling bonds.

“The bonds were printed by the continental bank note company in New York, which was a major producer of U.S. government currency,” explains Doherty, who acquired the aforementioned 1866 Fenian bond in the 1990s at a coin and currency show at the World Trade Center.

“The Fenians were smart enough to make a point of going to one of the top bank note companies. In other words, it was very professional. It really looks like a government bond. And that’s what you had to do. You were trying to persuade people to part with their money for just a little piece of paper. You had to impress them that this was something real,” he says.

“The bond had a six percent compounded interest per-annum from 1866. In fact, they were copying the confederates who issued all of their paper money saying ‘payable six months after the signing of the treaty of peace between the confederate states and the United States of America.” So the Fenians figured, ‘that’s a good idea. We’ll do that.’

“The bonds were widely disseminated and sold to the Irish American community. Most of the people who bought them were actually Irish immigrants. There were references made in the American magazines in New York at the time that ‘you’ll find your maids and your cooks and your butlers are spending the money you give them on these bonds.’”

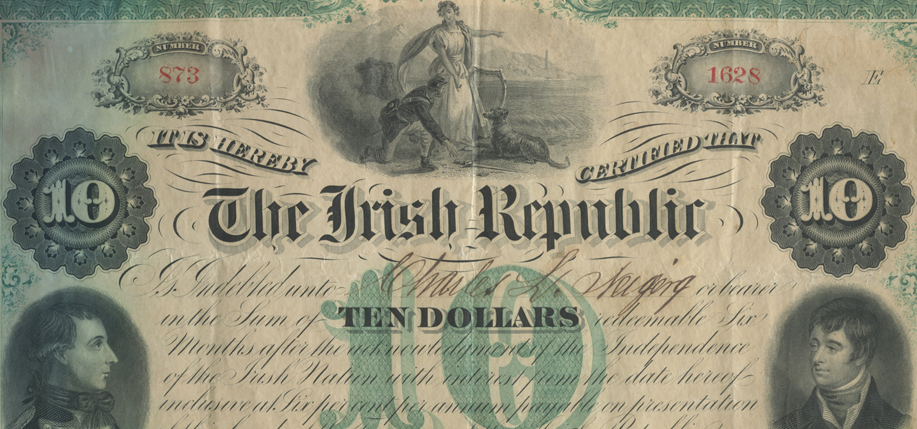

The bonds also feature some very iconic imagery, which Doherty was also able to decode.

“You can see up at the top, the vignette shows Mother Ireland with the hound and the harp – the national symbol. There is a soldier at her feet. He is an Irish veteran of the Civil War. So she is pointing down to the sword, and she is bidding him to pick up the sword again – and then she is pointing across the sea to Ireland. You can see a round tower – that’s Ireland. So she is saying pick up the sword again and fight.”

But the Fenian dream did not end as expected, ultimately rendering the bond useless as Doherty discovered when he attempted to cash it in several years ago. Doherty was in Dublin with a New York City delegation and arranged to meet the man in charge of the Irish treasury, Minister of Finance Brian Cowan (who would later serve as Taoiseach from 2008 to 2011).

“So I went in with that bond and with our delegation and I presented it to him for redemption! I said OK – it’s six percent compounded per-annum from 1866 – I estimated it was worth $22,000,” he says.

“[Cowan] ended up saying, ‘Is this the only one left? Are there others?’ I said, ‘there are others out there’ – and he said, ‘Well, I don’t know about that.’” Needless to say, Doherty didn’t end up cashing in on his $22,000 that day. But he’s optimistic.

He took it back from Cowan and pointed out that it reads “redeemable six months after the acknowledgement of the independence of the Irish nation.”

“One could say that the independence of the Irish nation as envisioned by the Fenians has yet to be achieved,” Doherty acknowledges. Since the Fenians envisioned an island free from British rule, there is the possible technicality that only a united Ireland would qualify.

“So I think I’ll hold on to this for a while, and see about redeeming it a little later.” ♦

Hello,

That is a very nice report. Are there any higher values such as $100 out there and are they scarce?

Yes..there are $100 denomination. I have one

Thank you. How much is a $100 bond to buy?.Were there any $500 or $1000 values ever issued?

yes there were $500’s. Very scarce and worth probable $10,000. & up