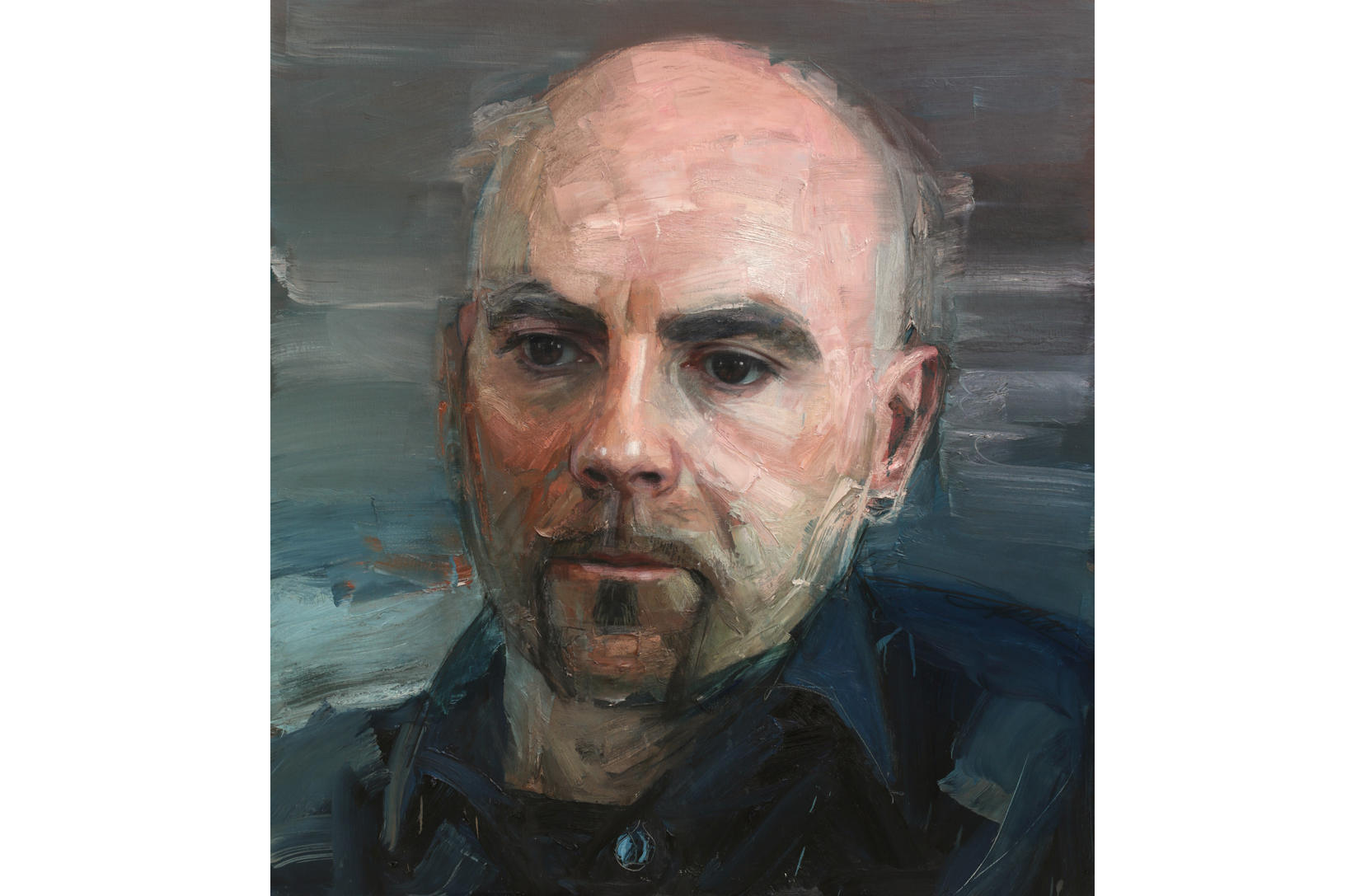

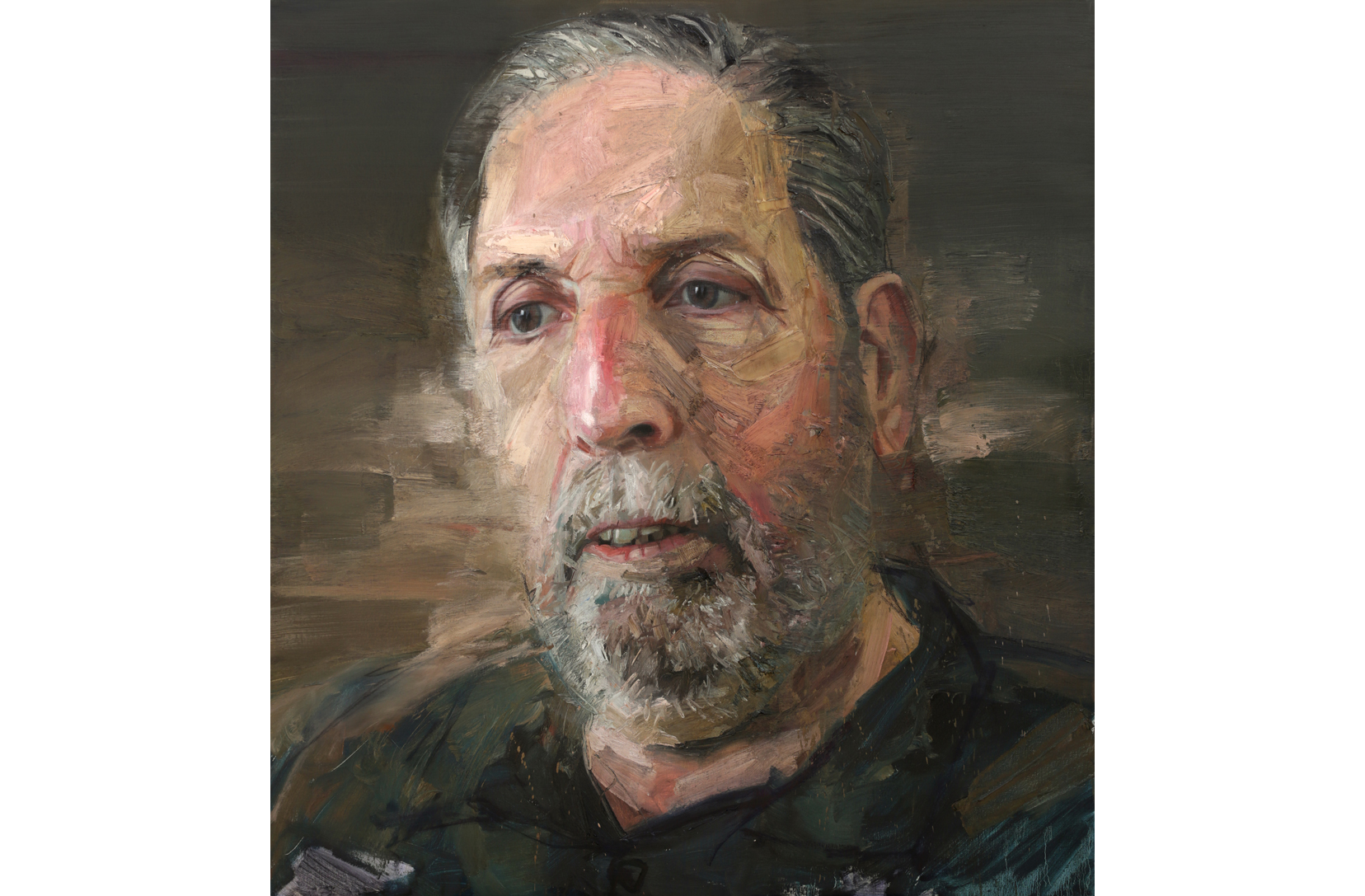

A new series of portrait paintings by Colin Davidson captures the suffering and loss that marked the lives of ordinary people and their families during the period known as the Troubles in his Native Northern Ireland.

℘℘℘

Colin Davidson, 48, is known for his striking large-scale portraits of celebrities such as Brad Pitt (which hangs in the Smithsonian), Liam Neeson, and other well-known figures, including Irish writers Brian Friel and Seamus Heaney.

More recently, his portrait of German leader Angela Merkel, was commissioned by TIME and ran on the magazine’s Person of the Year cover in December 2015.

But it is the artist’s new work, which explores the difficult topic of our past, that has people talking.

Titled “Silent Testimony,” the exhibition, currently on display at the Centre Culturel Irlandais in Paris, features large-scale portraits of 18 people who are connected by their individual experiences of loss and suffering caused by the Troubles, that 30-year period of Irish history in which 3,600 people were killed and many more were injured.

The exhibition showed at the Ulster Museum over several months through January 17, 2016, before moving to Paris. It drew people from across the country in Ireland, who were moved by the emotion Davidson captured in his series.

Born in Belfast in 1968, at the very start of the conflict, Davidson began working on the portraits over a three-year period. “It never started as a theme,” he said in a recent interview, but he recalled thinking, when he first heard of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, “what about all those who suffered losses during the conflict?”

He wanted to do something for “the people who hadn’t had a voice for the story they had to tell. Who had no escape from the grief – or no potential for justice.”

Davidson, who graduated from the University of Ulster in 1991 with a first class honors degree in design, chose to document the stories of his subjects, whom he met through Wave Trauma Centre, a support group for people traumatized as a result of the Troubles, without commenting on their religion.

“It’s human loss. It’s not Protestant loss or Catholic loss. It’s bereavement, full stop,” he said.

Prior to painting their portraits, none of the victims were known to the artists. The first time he met with them was on the day of the sitting. He described how he wanted that first meeting to be “raw.” “Everything I learned about the person I took back to the studio, and my release was to paint and express the horror that their stories brought forth,” he said. “Often it is the silences – the moments between the words, that are the most affecting.”

He added: “They are people who have suffered loss, and who are, in a sense, paying for our peace.”

Jean Caldwell’s husband Cecil, 37, was killed on January 17, 1992, when a land mine was detonated at Teebane Crossroads on the main Omagh to Cookstown Road. He and seven other colleagues died, and many others were injured, when the bomb destroyed their work van as they traveled home for the weekend. Cecil and Jean have two girls.

Damien McNally’s father, Paul, 26, was shot on June 5, 1976, in the Ardoyne district of Belfast. Paul and a friend were crossing Brompton Road after leaving a bookmakers in the early afternoon when two gunmen approached them. Paul died in hospital two days after the attack, knowing his injuries would be fatal. Damien was four months old and his sister, Karen, was four years of age.

Mary Finnis’s son Rory, 21, was shot dead in June 1991. Rory’s body, displaying evidence of torture, was found barefoot and hooded behind shops in the Creggan Estate in Derry. He had last been seen with a close friend in a city-center pub five days before his body was found on June 6, 1991. Mary still lives surrounded by photographs and mementos of her son. Rory’s son was just 18 months old at the time of his death.

Anna Cachart’s father, Patrick, 36, was shot dead on April 1, 1975, at his home in Carrickfergus. Patrick, who was born in India, had married a woman from Belfast and had three children. He was killed at home in front of his wife while his young children were asleep upstairs.

Walter Simon’s son Eugene, 26, disappeared on January 1, 1981. Eugene was a father of three children and had recently remarried following the death of his first wife. He was due to become a father again. Eugene’s body was recovered in May 1984 when a bog in County Louth was drained. His remains were identified by the rose gold Celtic cross, worn round his neck, that had belonged to his first wife.

Flo O’Riordan’s son Sean was killed on March 23, 1972, on Cawnpore Street in West Belfast. Sean received a gunshot wound to the back of the head and died a short time later in hospital. He was thirteen years old and was the second eldest of six children.

Thomas O’Brien was bereaved on Mary 17, 1974. His brother John, 23, sister-in-law Anna, 22, and two nieces, Jacqueline, 17 months, and Anne Marie, 5 months, were killed when a no-warning car bomb exploded as the young family were walking along Parnell Street in Dublin. A total of 33 people lost their lives that day in separate bombings in Dublin and Monaghan.

Emma Anthony’s father Frederick, 38, was killed on May 13, 1994, in his home-town of Lurgan by an under car booby trap bomb. His family was with him in the car. Emma, then three years of age, sustained serious injuries, as she was seated behind her father and was not expected to live. She still lives with the impact of her injuries.

Maureen Reid’s husband, and father of their ten children, James, 44, was killed on January 17, 1976, when a bomb was thrown into the Sheridan Bar in the New Lodge district of Belfast. Maureen never remarried and raised her family on a widow’s pension. Throughout the years, Maureen referred to James as “Daddy.” She passed away on March 25, 2015, with her family by her side. ♦

Leave a Reply