More than 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo. The vast lot of them got inked by way of an electric tattoo machine. And chances are they have no idea who invented the electric tattoo machine: Samuel O’Reilly.

His rambunctious, enigmatic life began in May 1854 in Waterbury, Connecticut. Both his parents were Irish immigrants, and he was the oldest of five children. At an early age, he – like so many other Waterbury residents of that era – began working in the brass industry (Waterbury is nicknamed “The Brass City”).

As a young adult, he sought to make money in other ways. According to Carmen Nyssen’s biographical essay on the website buzzworthytattoo.com, O’Reilly and two other Irish Americans were busted for burglary of a general store in 1873. For this incident, he served two years of hard labor in the state penitentiary.

Soon following his release, O’Reilly joined the Marine Corps, which he deserted after four months. For whatever reason, it doesn’t seem that he ever suffered any consequences for his desertion, but there would be consequences for other acts.

In April 1877, O’Reilly – along with his mother, father, and two of his four siblings – robbed a store. In the wake of this family outing, O’Reilly, knowing that there were warrants for his arrest, skipped town and headed for Detroit.

The wanted man knocked around Detroit without much of a purpose other than eluding authorities. Evidently, he grew sick of life on the run. The October 25, 1878 issue of the Detroit Free Press tells how O’Reilly, who was having “no luck” in Detroit, turned himself in to a beat officer whom he had befriended. Suspicion was expressed that the fugitive turned himself in to authorities so he could obtain a free ride back to Connecticut.

O’Reilly received his ride and then received five years in state prison. He was now in his mid-twenties, and it seemed that prison would become his way of life. But as it turned out, Samuel O’Reilly had much more to offer this world than common criminality.

It is unknown where O’Reilly ventured right after his second state prison stint. He resurfaces as a tattoo artist in mid-1880s New York City, where he was billing himself as “Professor O’Reilly.” He launched a tattoo studio at 11 Chatham Square, in the Chinatown section of Manhattan’s Bowery.

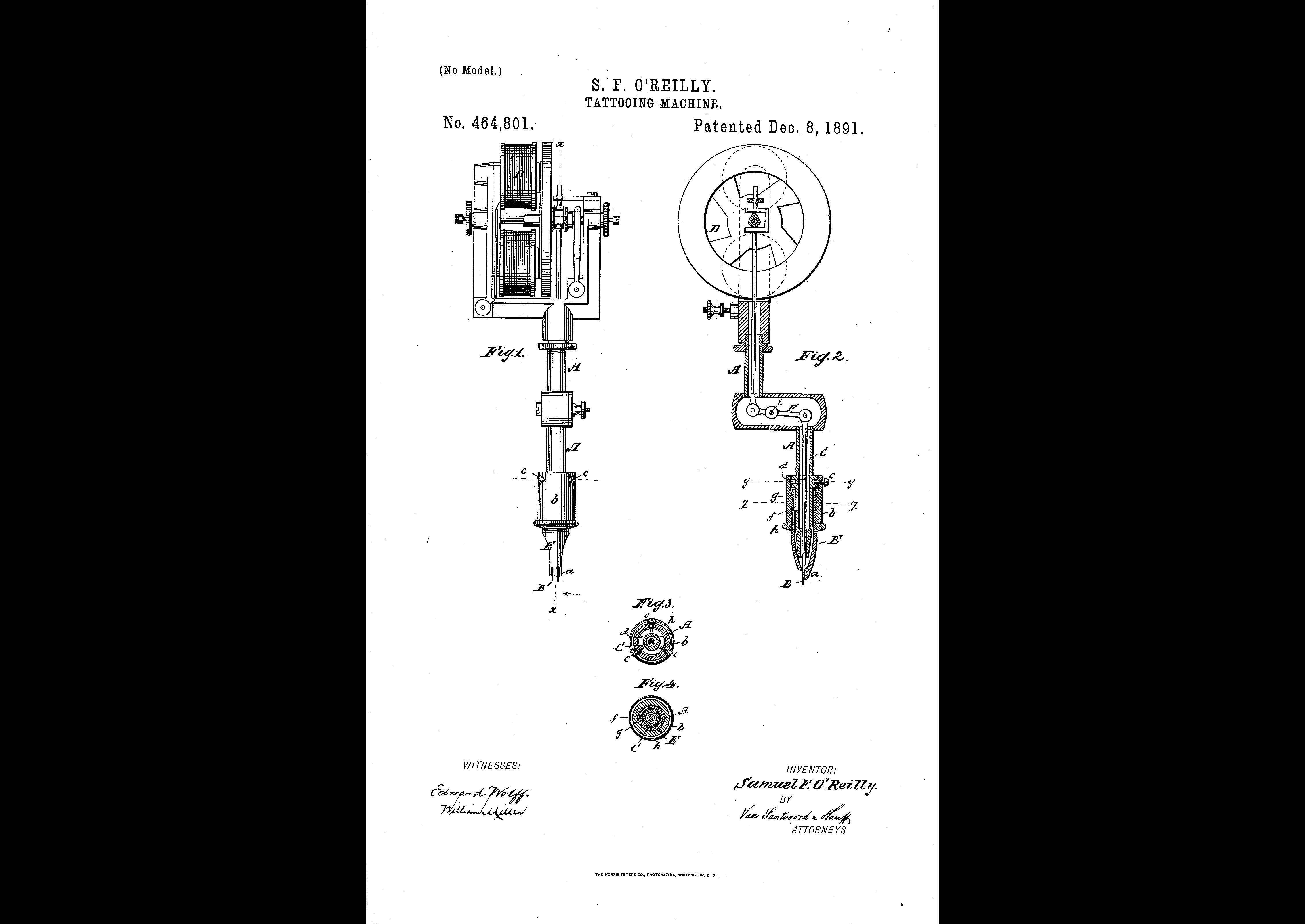

At that time, his tattooing instrument consisted of a set of needles affixed to a wooden handle. He eventually figured there had to be a better way. Knowing that the inventor-extraordinaire Thomas Edison had been tinkering around with pens connected to motors, O’Reilly applied this concept to tattooing, and his patent (No. 464,801) for an electric rotary tattoo machine was issued on December 8, 1891.

The tattoo industry was “revolutionized overnight,” according to Steve Gilbert’s “Tattoo History: A Source Book,” which adds that, “O’Reilly was swamped with orders and made a small fortune within a few years.” His electric machine was capable of making many more punctures per minute, and its puncturing was more precise – resulting in more accurate tattoos and less bleeding for the recipient.

Not only was he an innovative craftsman, but Prof. O’Reilly also would become the leading tattoo artist of his era. Perhaps the ultimate confirmation of his talents was that even circus tattoo-freaks sought out his services so they could revivify their illustrated bodies. But as tattoos became more popular, these circus tattoo-freaks were losing business, as their ink-laden bodies were no longer that rare.

O’Reilly’s steadiest source of clientele was the U.S. Navy. In his view, an American sailor without a tattoo was “not seaworthy,” according to Albert Parry’s Tattoo:

Secrets of a Strange Art. The inventor’s studio often was packed with young men looking to be “seaworthy.”

A shrewd marketer, O’Reilly circulated a pamphlet about tattooed U.S. military members fighting in the Spanish-American War. Part of this pamphlet reads: “Brave fellows! Little fear had they of shot and shell amid the smoke of battle, and after the scrub down they gloried in their tattoos.”

He also tapped into the Irish-American market with his illustrations of Irish and American flags intertwined, frequently accompanied by “Erin Go Bragh.”

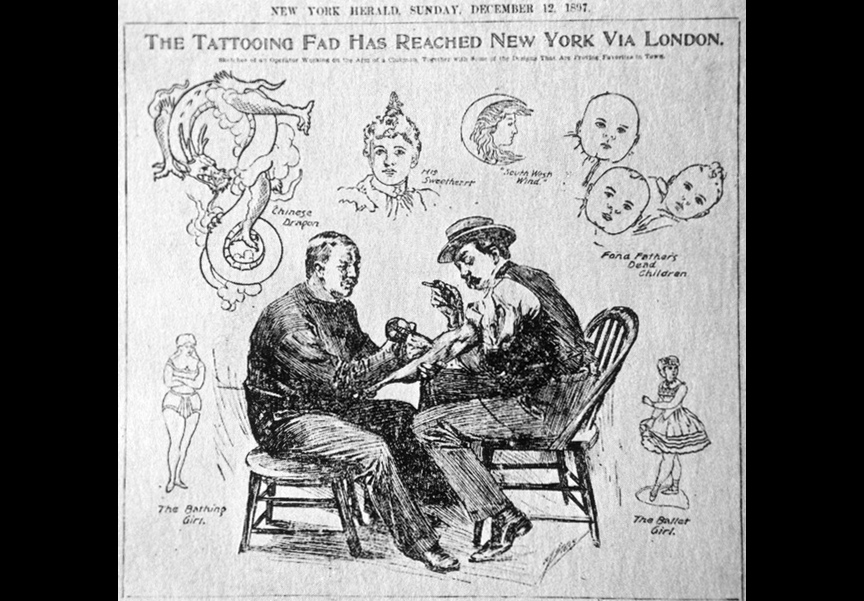

As the 20th century approached, at least one tattoo studio could be found in every major U.S. city. Not everyone was pleased with this phenomenon. Ward McAllister, a self-styled spokesman for New York high society, declared of tattooing: “It is certainly the most vulgar and barbarous habit the eccentric mind of fashion ever invented. It may do for an illiterate seaman, but hardly for an aristocrat.”

However, even the ‘aristocrats’ were getting inked. In fact, a sensationalistic August 1897 report in the New York World said that “three-quarters of the society women in America were tattooed.” This statistic likely was much exaggerated, but people of high society were getting inked. Prof. O’Reilly made house calls (and even was commissioned to travel to other cities) to these patrician types who would not condescend to set foot in his plebian-frequented Bowery studio.

At the beginning of the 20th century, O’Reilly was no longer as prolific as he had been, and much of his energies were devoted to lawsuits against tattoo machine manufacturers who he felt were committing trademark infringement on his patent.

In April 1909, O’Reilly, age 54, was painting his house at 1831 Nostrand Avenue in Brooklyn. Suddenly the scaffolding on which he was working gave way, and the ensuing fall fractured his skull. He was brought to Kings County Hospital, where he succumbed to a brain hemorrhage. His eternal resting place is in Holy Cross Cemetery in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

He left images on so many people, yet we have no certain image of him, as no O’Reilly photographs are known to exist. One indication of his appearance is a slightly flippant Brooklyn Daily Eagle obituary, which describes O’Reilly, a.k.a. “Tattoo Man,” as “one mass of tattoo marks from head to foot.” It seems that, upon coming to New York, he treated others as he wished to be treated. ♦

Leave a Reply