In 1991, Irish America magazine published one of the first interviews with Gerry Adams. (As far as we can tell, Playboy was the only other American magazine to interview Adams before that.) In March, of that year, as the 75th Anniversary of the 1916 Rising loomed and violence continued on both sides in Northern Ireland, Patricia Harty traveled to West Belfast to interview the Sinn Féin leader. In that interview with Harty, Adams talked about the need for all-party talks and called for Irish American help in ending the conflict.

Twenty-five years on, Adams reflects on the legacy of Irish America, the Rising, the monumental changes that have since taken place in Northern Ireland, and the work that still need to be done.

At the beginning of 1916, James Connolly said: “…opportunities are for those who seize them.”

Twenty-five years ago, in 1991, there did not appear to be too many opportunities to be grasped for peace.On February 7th IRA mortars landed in the back garden of 10 Downing Street. Some years later Martin McGuinness and I were to stand in that same garden looking at the still visible signs of the shrapnel damage on the walls. We were discussing with Tony Blair and Bertie Ahern how we were going to overcome another crisis in the peace process.

1991 was also the year the Birmingham Six were released after decades of campaigning; IRA attacks against British forces continued; as did loyalist attacks against Catholics, many of them involving direct collusion with British state forces. Donegal Sinn Féin Councillor Eddie Fullerton was shot dead, as was Councillor Bernard O’Hagan in south Derry. And over the summer 1,000 additional British troops were sent into South Armagh where they reinforced, rebuilt or constructed new hilltop forts.

A report by the British government’s Fair Employment Commission again showed that Catholics in the north were still two-and-a-half times more likely to be unemployed than Protestants.

Talks involving all of the parties – excluding Sinn Féin – and the two governments, started and ended with no progress.

Kadar Asmal, was the Chairperson of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in Ireland, and a lecturer in law in Dublin. He subsequently became a Minister in the post-apartheid South African government. In a report published that year into British Shoot-to-kill operations in which hundreds died he concluded that “the whole administration of justice is perverted and the vocabulary of dissent itself is prostituted. The use of special courts … the lethal use of firearms to remove people who are embarrassments to the policies of the administration … the United Kingdom is behaving and has behaved in the north in the same way that colonial powers exerted their sovereignty in the old-fashioned empires.”

In July 1991, a year after the back channel between republicans and the British government were secretly reopened, a new British government representative met with the Derry group who were acting as facilitators. I also wrote to the two governments, to other party leaders, church leaders and others seeking open ended discussions on the conflict in the north and arguing for the development of a peace process. But very few, at least publicly, were prepared to stick their necks out to discuss these matters with us. The two governments were talking to us secretly so we shrugged our shoulders each time we heard a Minister from either government attack Sinn Féin and reject discussions with us. Toward the end of the year John Hume, with my approval, privately brought a draft of a joint declaration to be made by the two governments to the Haughey government.

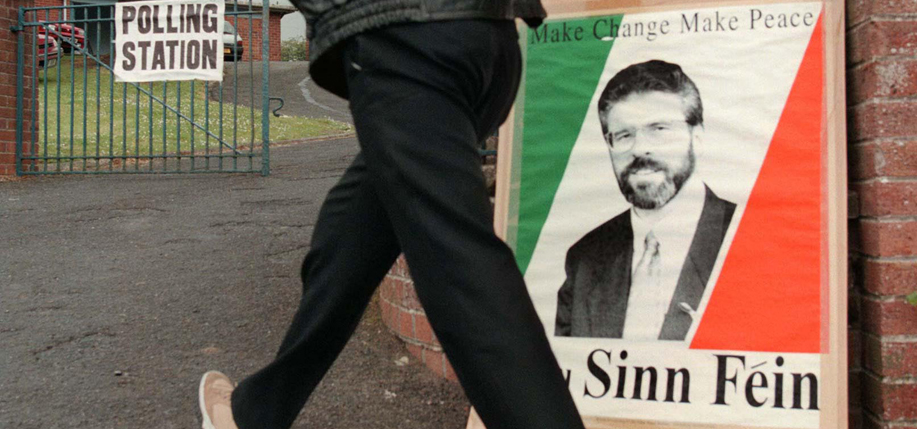

1991 also saw Sinn Féin draw up a peace proposal “Towards a lasting Peace in Ireland” – that was launched at our Árd Fheis (annual party conference) early in 1992.

Twenty-five years ago the war was raging as it had for the previous two decades but under the surface Sinn Féin’s efforts to create the conditions for a peace process were taking shape. The Sinn Féin leadership was now exploring positions secretly with the British, talking privately to John Hume and also dealing indirectly but separately with the Irish government through the Sagart – Fr. Reid.

We had also begun to explore tentatively with supporters and others in the USA what contribution if any could come from that country. For over 100 years Irish America had played a key part in the struggle for freedom and justice in Ireland. From the foundation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and Clann na Gael in the nineteenth century; through the financial support provided for the 1916 Rising and the Black and Tan War, and up to recent decades Irish America was intimately involved in the Irish struggle for freedom.

The 1916 Proclamation explicitly praises the role of the Irish in America; “and, supported by her exiled children in America.”

In the 1970’s Irish America supported oppressed communities in the north. Many children were brought to the USA on holidays designed to provide relief from the reality of conflict and British military occupation. In the 1980’s Irish America was in the frontline of the efforts to end structured political and religious discrimination in employment through the MacBride Principles Campaign.

Irish America also successfully raised justice issues like the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four (who were wrongly accused of pub bombings in Birmingham and Gilford), plastic bullets and internment, and the conditions in the H Blocks.

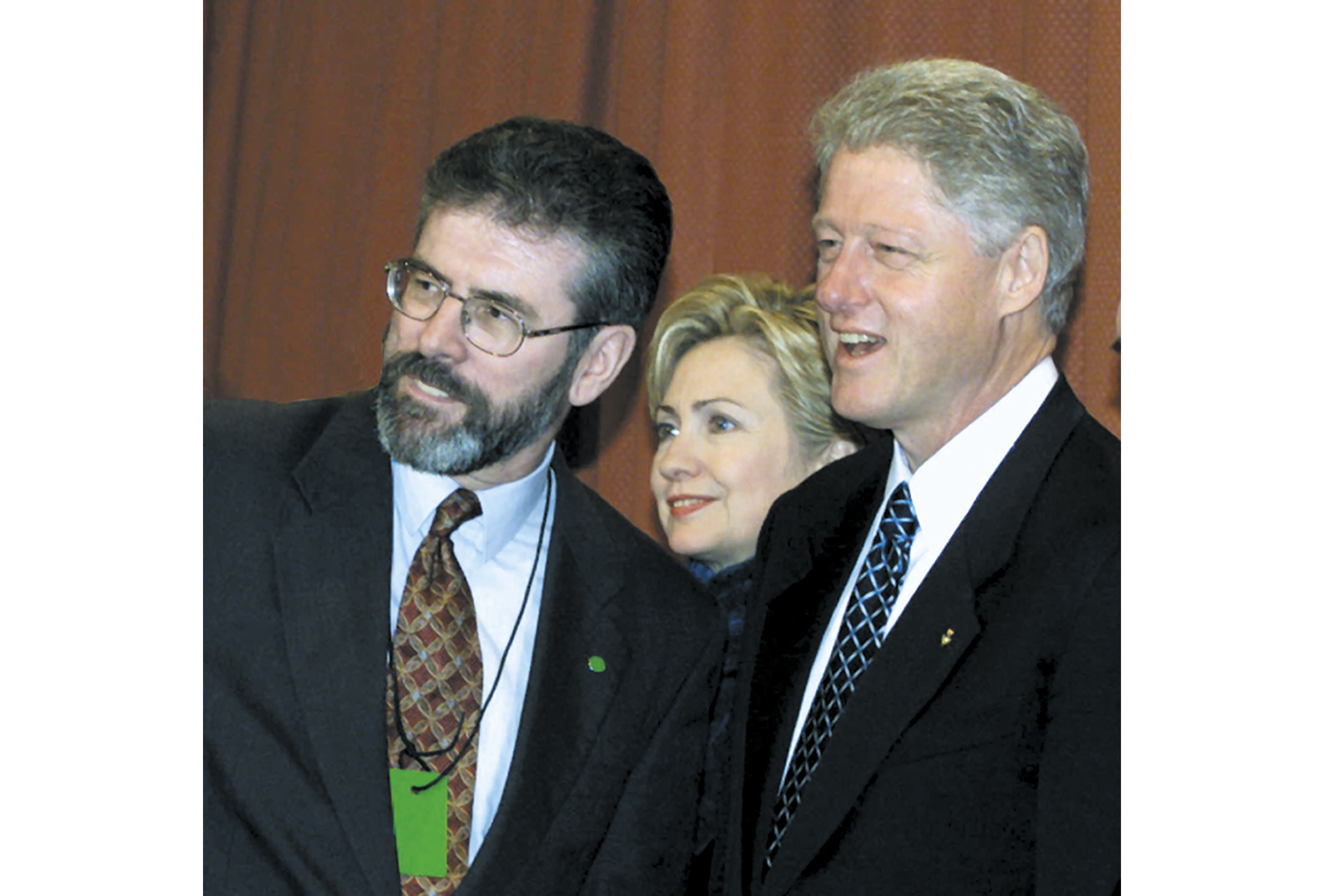

But it was with the development of the peace process that Irish America and others in the Irish diaspora around the globe really played a key part. In the years immediately after 1991 the decision by President Bill Clinton to become involved in the search for peace was down to the valiant efforts of Irish Americans like Niall O’Dowd and Bill Flynn, Bruce Morrison, Joe Jameson, Chuck Feeney and groups like Noraid and Clann na Gael and many others.

Lobbying by Irish America saw Bill Clinton commit to playing a more active role in working to “achieve a just and lasting settlement of the conflict” in Ireland if he was elected. At an event organized by John Dearie he committed his Presidency to the appointment of a special U.S. envoy to the north because he believed that such a move “could be a catalyst in the effort to secure a lasting peace.”

The day after Bill Clinton’s inauguration a British government spokesperson in London told the media that its priority would be to have the idea of the envoy scrapped. But Irish America persevered and President Clinton kept his commitments. The following January, I was given a 48 hour visa for New York to attend a conference organized by the National Committee on Foreign Policy, which was then chaired by Bill Flynn.

The subsequent appointment by President Clinton of George Mitchell and the succeeding U.S. special envoys, all of whom played a positive role, had an important and constructive impact on the peace process.

The rest as they say is history. But it is a history which has a direct bearing on decisions still being taken and ongoing efforts to ensure the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement.

In the years since then Irish America has remained a constant source of support and encouragement for the peace process. It has consistently contributed to the efforts to overcome each of the crises that have bedevilled the process, kept the White House and U.S. political system engaged with the process and has never given up on the democratic imperative of Irish reunification.

And that is the key. One hundred years after the Rising the partition of Ireland and the continued involvement of the British in a part of our island is the unfinished business of 1916.

One hundred years after the Rising many Irish Americans who continue to be involved in the ongoing efforts to ensure the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement and subsequent agreements, will be travelling to Ireland to take part in the centenary celebrations.

It is an exciting time in Ireland. It is a time for fundamental change. A time when the Irish republican goals of unity and equality and peace can take a giant step forward.

Twenty-five years ago the north was a byword for conflict and sectarianism; for violence and division. Today it is a beacon of light in a world riven with war. An example of what is possible if leaders are prepared to take risks for peace.

Life on the ground has been transformed. Young people today have hope. No one born in 1991 will have a memory of British soldiers on our streets or house raids or bombs or fear.

Of course, there is still much work to be done. The peace process cannot – must not – be taken for granted. Crucial parts of the Good Friday and other agreements have still not been implemented. The British government refuses to face up to the legacy issues that scar those who survived the conflict. There are some – a tiny unrepresentative minority – who would like to turn the clock back. They must be opposed.

1916 was a transformative moment in Irish history. Those who took part in the Rising gave their lives and liberty, to deliver the republic enshrined in the proclamation; a republic built on the principles of equality and sovereignty, of human rights and civil liberties, and of unity and nationhood. Principles that remain a challenge to successive governments in the Irish state. 2016 can also be a transformative moment in Irish history. Join us in this great historic endeavor. ♦

Leave a Reply