Robert Schmuhl takes us behind the scenes on a decade-long research project that culminated in his book Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising.

Facts are stubborn things,” John Adams famously remarked. Less known, though, is a clause he added to complete the thought – “and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Mulish facts and elusive evidence have become (metaphorically speaking) my constant companions the past decade. Beginning in 2006, I started doing initial spadework for a research project about the 1916 Easter Rising, probing its American relationships and connections. Now – and just in time for the commemoration – the book has entered the world.

Writing a book, any book, becomes an education. For this one, it meant not only coming to terms with people and events a century ago, but also with the ways those people and events were interpreted during recent decades.

A principal lesson I learned early on was the wisdom of Adams in emphasizing the stubbornness, yet supremacy, of facts. They provide the necessary

evidence and foundation without which an historical account might be inaccurate, even rickety.

A general statement about what scholarly lingo calls factuality is a toddler step toward understanding the actual process of arriving in the vicinity of truth. In many cases, though, what might appear at first as easily retrievable information can involve a forced march through briars and thickets of documents that, alas, don’t prove the point you’re trying to make.

Consider a key figure in my book: John Devoy. Exiled to the U.S. in 1871 after being convicted for treason in Ireland, he provided much of the financial support to launch the Rising. Though Devoy worked in the shadows as a leader of Clan na Gael (the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s American counterpart), he also founded and edited The Gaelic American, a weekly newspaper that promoted physical-force republicanism.

Gag Order

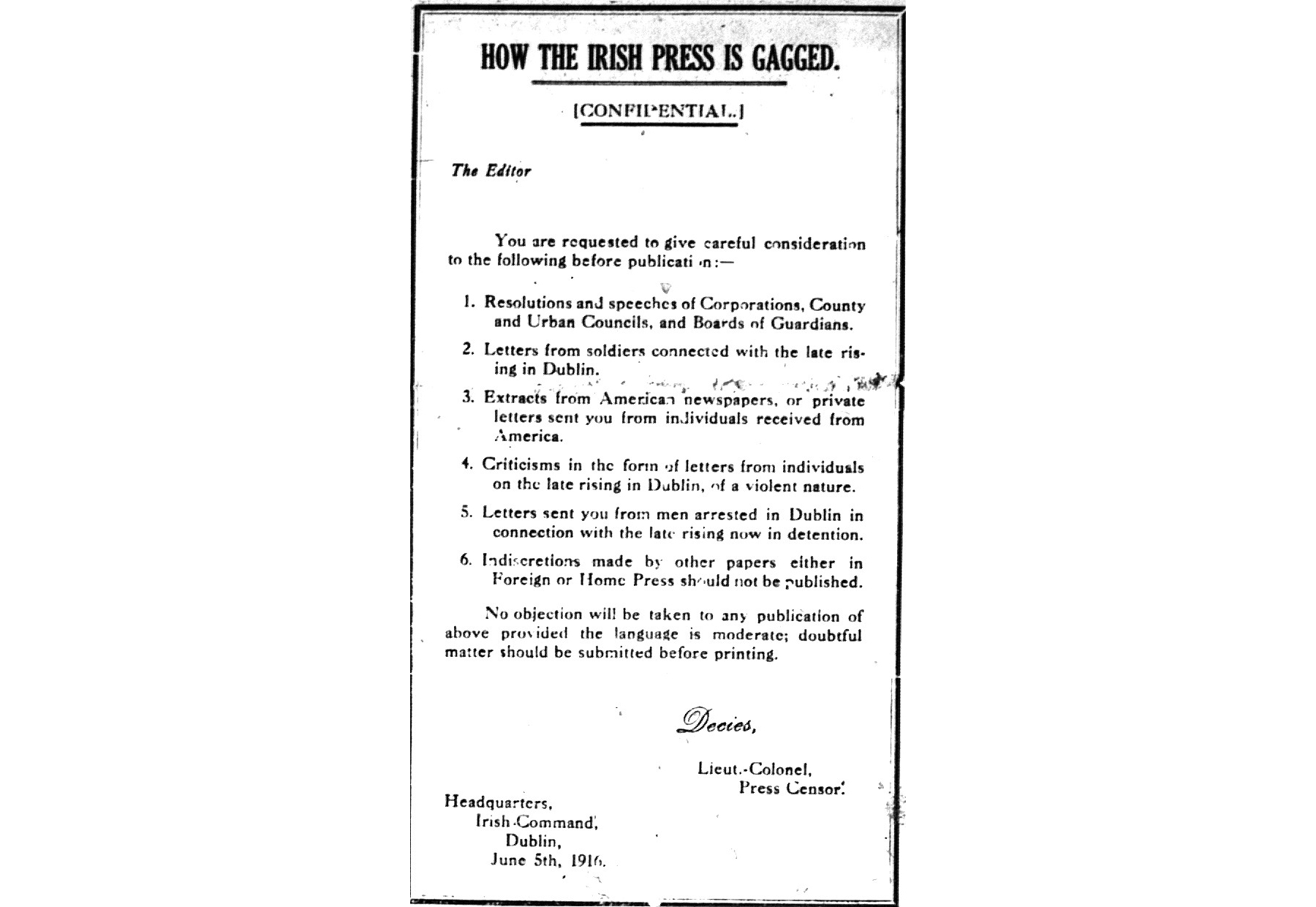

The July 8, 1916 edition of Devoy’s paper published a boxed list – putatively prepared by the British press censor in Dublin – warning editors of Irish publications “to give careful consideration” before printing specific types of information. In the post-Rising environment, the censor’s office (established on June 1) wanted strong control over journalism in Ireland.

The box carried an opinionated headline – “How the Irish Press is Gagged” – and, for my purposes, an intriguing third item: “Extracts from American newspapers, or private letters sent you from individuals received from America.” Were U.S. papers and people reporting news to promote the rebel cause?

Given that The Gaelic American reflected Devoy’s anti-British viewpoint on every page, actual proof that the censor’s document existed and was faithfully reprinted seemed essential if I were going to quote it. But where to turn?

Some rudimentary research in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin went nowhere, so I strolled over to the National Archives and inquired there. A staff member suggested that the “Press Censorship Records, 1916 – 1919” might substantiate the directive’s existence.

Three large boxes comprise this set of official papers, and the files are organized somewhat haphazardly. By “somewhat” I mean that individual folders contain related information – but there is neither rhyme nor reason, let alone chronology, to the ordering of the folders.

It’s as though documents were dumped in one box until it became full, and then the two others were treated with the same random system of stacking. What to do?

Well, for a full day and a half, I sat there methodically working through each folder, losing hope and good cheer by the hour. Finally, during the afternoon of the second day – in box 3 and folder 128 to be exact – Eureka!

The National Archives isn’t an appropriate place to scream or yell, so I just sat there in restrained jubilation, comparing what Devoy ran in his newspaper to the censor’s formal statement. Word-for-word the two matched, ending that particular evidential odyssey.

Name Calling

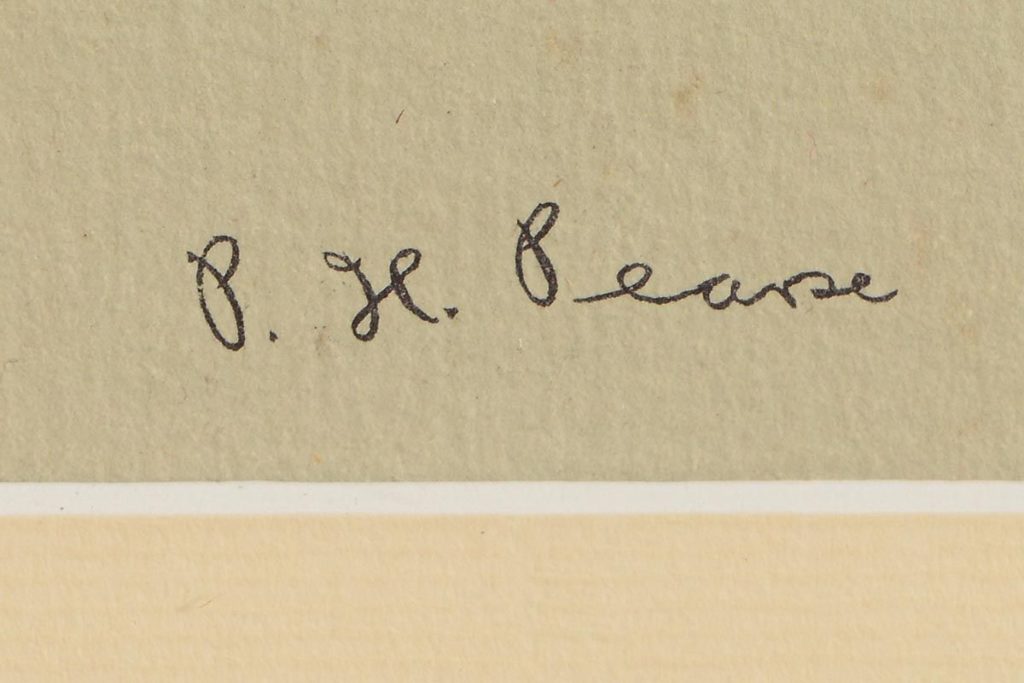

“What’s in a name?” Shakespeare wondered in Romeo and Juliet, and the same question might be asked about P.H. Pearse, the “President of the Provisional Government” who read the Proclamation of the Republic on the steps of Dublin’s General Post Office at the start of the Rising.

The “P” and “H” of Pearse’s name – he used the initials when he signed documents – refer to “Patrick” and “Henry.” For an American, mention of “Patrick Henry” prompts memories of grade-school history, and a much-quoted line of oratory the revolutionary hero from Virginia thundered in 1775. “I know not what course others may take,” he said, “but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

Several books published in the U.S. praise Pearse’s parents for their transatlantic clairvoyance. “His English father,” one author states, “was sufficiently anti-imperialist to name his son Patrick Henry,” while another is even more explicit: “In a prescient gesture, Pádraig – the second of four children – was named not after the patron saint, but after the American patriot Patrick Henry.”

Inspiring as it sounds, it’s not true. In an autobiographical reminiscence about his boyhood, Pearse explains that he was named for a great uncle (Patrick) and his father’s youngest brother (Henry).

And just how “anti-imperialist” was Pearse’s father? According to John J. Horgan, the nationalist politician and writer in his book, Parnell to Pearse (1948), a “friend of mine . . . used to tell how once, having occasion to call on the older Pearse, he found him in his yard practicing with a revolver so that he might be able to defend himself from the Fenians, the Irish revolutionaries of that period, whom he naturally considered a threat to his freedom, but whose example later inspired his son to rebel.”

De Valera’s Escape

Wrestling with sources that provide conflicting information is just one occupational hazard for the writer of any historical narrative. But what do you do with inconsistent accounts from the same source?

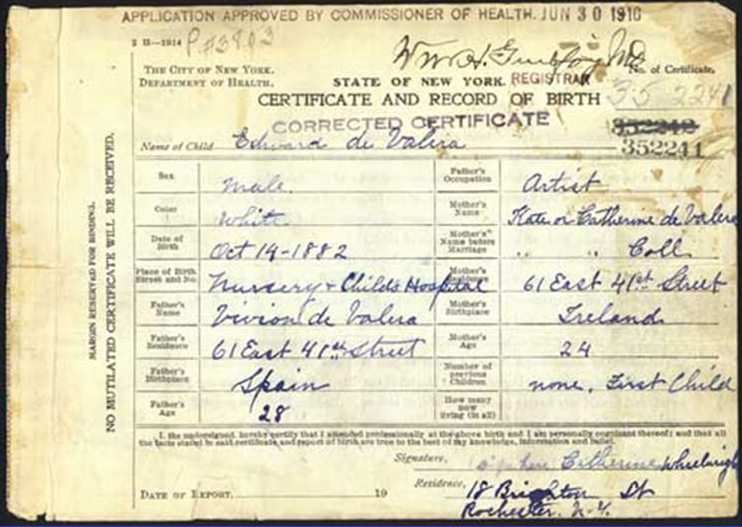

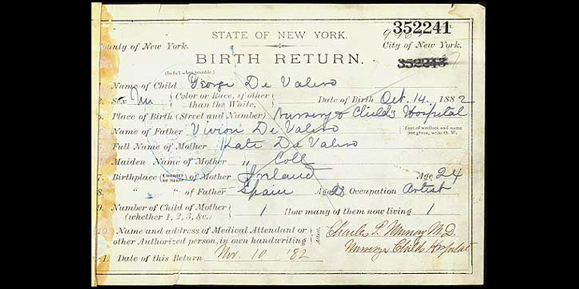

In the Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009), Ronan Fanning, professor of modern history at University College Dublin for many years, provides this telling insight about Éamon de Valera: “. . . what he did in the rising mattered little when set against the iconic stature he acquired in its aftermath as the only surviving commandant, when his sentence of death on 8 May by a military court was commuted to life imprisonment.” Fanning goes on to say de Valera’s “escape owed more to luck” than other factors.

That seems definite enough. But in Fatal Path (2013), a study of British government policy vis-à-vis Ireland from 1910 to 1922, Fanning writes: “Fifteen executions were carried out between 3 and 12 May: all seven signatories of the proclamation and all the Volunteer commandants except one were shot. Éamon de Valera escaped death because of his American birth.”

Confused? Then in Fanning’s new biography Éamon de Valera: A Will to Power (2015), he says, “the mere fact of his [de Valera’s] American birth fuelled a myth that endured.” Now we’re operating in the realm of myth rather than fact about the reprieve.

The historian then seems to return to his judgment in the DIB, saying: “The truth is simpler: de Valera owed his survival more to luck than to [British prime minister Henry] Asquith or America.” However, one paragraph later, we read these words: “. . . Éamon de Valera survived in 1916 because he was unknown.”

Well, what exactly saved de Valera? I suppose if you stretch your thinking you might say being lucky and being unknown can be interpreted in vaguely similar ways. Yet, however you look at these quotations, basic facts seem in dispute – and they’re presented by the same respected source.

One of Seamus Heaney’s most memorable poems, “Digging,” juxtaposes the spade wielded by his father and grandfather – as they cut the sod in search of “the good turf” – with the poet’s “squat pen.”

Finding that “good turf” of accurate historical information requires a different kind of digging from Heaney’s literary art – but (in his phrase) “going down and down” will take another kind of wordsmith closer to the truth of all those stubborn facts and also help explain how they dance together. ♦

Bob,

Very interesting info about a part of history (of which there are many) that I have thought little about and about which I know less. I suspect a lot of history as we know would be a bit different if facts were always deemed essential. Looking forward to the book. Congratulatons.

Mike Englert

I am quite pleased to see more scholarly work being done on DeValera’s family. The pictured birth certificates were my discovery during my tenure as Commissioner of the NYC Dept. of Records, and thus the reason we have these quality scans of the originals. Looking forward to more discussion. Great work.