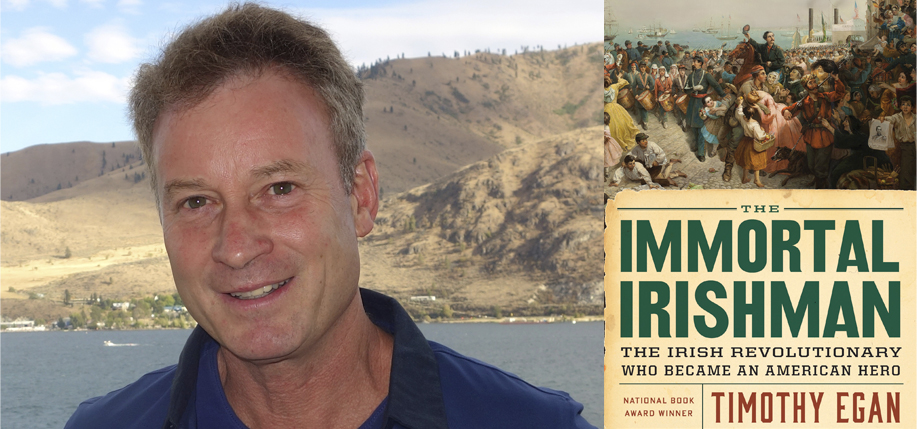

Timothy Egan (born November 8, 1954 in Seattle, Washington) has written eight books including the newly released Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero, about Thomas Francis Meagher. His book, The Worst Hard Time, about people who lived through the Great Depression’s Dust Bowl, won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. A Pulitzer Prize- winning reporter as well as an author, Egan is a New York Times Contributing Op-Ed Writer, covering the environment, the American West and politics.

Tell me about your Irish heritage.

I’m descended from Egans and Lynches. On my mother’s side we can definitively trace to County Waterford, and then to Butte, Montana, where my great-grandfather settled and probably had something to do with the movement to erect a statue of Thomas F. Meagher in 1905. My father lost his dad when he was two years old and was raised by a single mom in Chicago, living above a bar. We haven’t been able to trace those Egans. But from both parents, I got a sense of storytelling, and love of the underdog, and finding joy in the margins. I’m one of seven children.

When did you become interested in Meagher?

I became interested in Meagher after the Montana governor, Brian Schweitzer, showed me the statue outside the capitol at Helena, Montana. I said, “Who the hell’s that guy?” And he said, “You call yourself an Irish-American and you don’t know who Thomas Francis Meagher is?” In fact, I didn’t, but neither do most Irish Americans. To think they had a convict, wanted by the British Empire, as their territorial governor, the Irish General of the Civil War, the Young Ireland rebel – it all defies credulity.

Did you know a lot about Irish history before you started researching?

I knew a fair amount about Irish history because I studied at the University of Washington in Seattle, under the late Dr. Giovanni Costigan, one of the most passionate scholars of our story. His classes were always packed. I was somewhat of a lapsed Irishmen until I took his classes.

Your writing on the Famine era is especially evocative – did researching this period in Irish history leave a lasting impression on you?

The Famine period is something everyone should know. I thank Dr. Christine Kinealy at Quinnipiac for her scholarship on this. But I was stunned at the things I learned, and the fact that a million Irish died during a time of plenty, when there was, in fact, plenty of food on the island.

How long did the book take your to write – from beginning the research to finished manuscript?

It took me about four years to write the book, while doing other topics as well. Once I get the material, I’m a fairly fast writer. Here, it was the research – from Kilmainham Gaol, to the Civil War battlefields, to Fort Benton, Montana – that was so stirring. That where I looked for textural details to make the story come alive.

Did your research take you to Ireland?

Three trips on this book, and I loved sitting in the National Library of Ireland reading all the notes, letters and speeches of the Young Ireland rebels. I went to Meagher’s home in Waterford – now the Granville Hotel, on the River Suir, and you see how proud they are of him for giving Ireland its national flag.

Much of your writing is concerned with environmental issues, where does that interest stem from?

I’ve always loved the outdoors. Meagher was rhapsodic about the land, once he came to Montana, and the National Park Service credits him with being one of the first people to suggest that Yellowstone could be a park – one of many amazing things about a man who lived twelve lives in one, who shaped events on three continents. ♦

Tim, hello my is Terry Egan and I’m from Burlington, Iowa. I am in the process still, of tracing my Egan ancestors. I come from a family of 10 and also I was born in 1954, May 2nd. My great-great-grandfather, John Egan came to America in 1845 and ended up settling in Northeast Iowa in 1860. They had seven children and I’ve been able to trace all with the exception of three sons and only up to around 1890. The three sons were John, Edward and Francis. I was wondering what your grandfather and your father’s names were? By looking at your picture you could easily be mistaken as a brother of mine. Looking forward to hear from you.

Best regards,

Terrance Egan