When the rebellion of 1798 failed, many of The United Irishmen, including Thomas Addis Emmet, came to the United States where their influence was enormous.

You may well wonder why a historian of the United States should presume to write about the United Irishmen of 1798. There are two reasons: one personal, the other historical.

The personal reason is that I had the great good luck to marry an Emmet in the direct line of descent from the Thomas Addis Emmet – an act that has improved me as much as it has enlivened and enriched my life. Also, growing up in Massachusetts, I was plunged from an early age into Irish-American ways, forming lifelong friendships with Edwin O’Connor of The Last Hurrah, with Frances Sweeney of the Irish-American Defense Committee, with Monsignor Frank Lally of the Boston Pilot, with Tip O’Neill, and with a family named Kennedy.

The historical reason is that the fate of the United Irishmen of 1798 has, from the start, been entangled with the fate of the United States of America. For it was the American Revolution that first inspired the United Irishmen in their bid for Irish independence. As John Caldwell, a Presbyterian radical from County Antrim (let us not forget that many of the United Irishmen, including the Emmets, were Protestants), later recalled it, “On the news of the battle of Bunker Hill, my nurse Ann Orr led me to the top of a mount on a midsummer eve, where the young and the aged were assembled before a blazing bonfire to celebrate what they considered the triumph of America over British despotism.”

When John Paul Jones, the dashing American naval commander, sailed his sloop Ranger into Belfast harbor in 1778, he was unopposed and applauded. When the British government, losing the war in America and fearing trouble in Ireland, made the concession in 1782 of an Irish Parliament, one Irishman said, “It was on the plains of America that Ireland obtained her freedom.” The Irish patriot Henry Grattan declared, “The American war was the Irish harvest.”

Grattan’s “revolution of 1782” turned out to be a false dawn. In the next decade the United Irishmen, additionally inspired by the French Revolution, arose to carry forward the struggle. When forced underground, the United Irishmen developed a catechism by which members could recognize one another. It went like this: “What have you got in your hand? – A green bough. – Where did it first grow? – In America. – Where did it bud? – In France. – Where are you going to plant it? – In the crown of Great Britain.” Wolfe Tone, after his capture and condemnation by the English, said (in his speech from the dock), “In the glorious race of patriotism, I have pursued the path chalked out by Washington in America.”

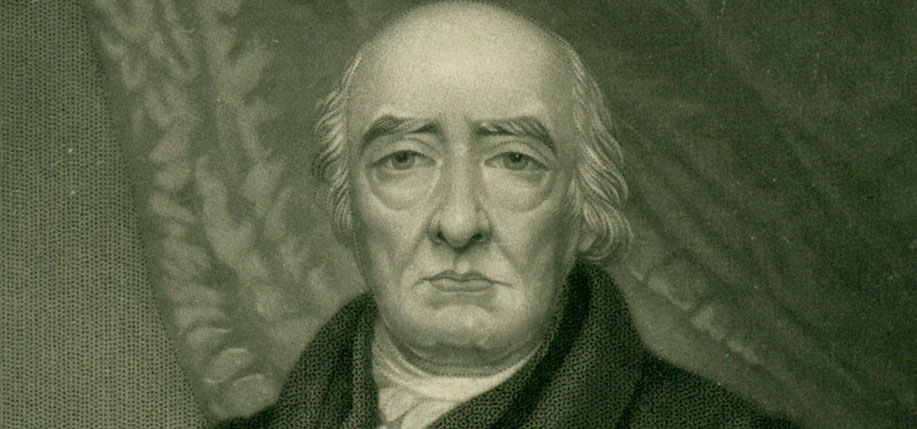

Thomas Addis Emmet was in the center of all this, and his younger brother Robert became the historic martyr to the cause, when he was hanged by the British in 1803. The United Irishmen had, it must be confessed, their own internal fights. “The Irish are a fair people,” as Dr. Johnson said, “they never speak well of one another.” Or, as George Mitchell once put it, “An Irishman will go a hundred miles out of his way to receive an insult.”

The feud between Thomas Addis Emmet and Arthur O’Connor came close to turning the United Irishmen into the Disunited Irishmen. William Drennan, who wrote the original United Irishmen prospectus, described Thomas Addis Emmet as “possessing more eloquence than energy, more caution than action.” But it is not at all clear that Emmet was wrong in doing his best to restrain the firebrands.

Emmet rightly understood that democracy is at bottom an educational process. The great need, he thought, was to instill democratic values in the citizenry in order, as he put it, to “make every man a politician.” In his study of the rebellion of 1798, The Year of Liberty, Thomas Pekenham concludes that Thomas Addis Emmet was “undoubtedly the most talented and level-headed of all the United Irishmen.”

After the collapse of the rebellion and the arrest of its leaders, Emmet and others were put in British jails. Discharged from imprisonment on the understanding that he would go into permanent exile, Emmet decided in 1804 to take his chances on the other side of the Atlantic. This had not been his first thought. Asked in 1798 where he would seek refuge, Emmet replied, “Decidedly not America.” But that was the America of the Federalists, the party that had just passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws appeared to be aimed directly at people like Thomas Addis Emmet, well known as an alien with a fine reputation for sedition.

The election in 1800 of Thomas Jefferson as president portended a different United States. Thomas Addis’s mother wrote him, “Ever since Jefferson has been chosen, I have expected that in America you would reside.” Three days after Emmet disembarked in New York, he applied for naturalization papers. Qualified to practice both medicine and law, he decided on a legal career and rapidly rose to the top of the New York bar. A short eight years after his arrival, he was appointed Attorney General of the state of New York.

In private practice, Emmet argued important cases before the Supreme Court, notably against the great Daniel Webster in the famous 1824 case of Gibbons v. Ogden. Here Emmet did his eloquent best to preserve Robert Fulton’s state-chartered monopoly of steamboat traffic in New York waters, but lost to Daniel Webster’s – and Chief Justice John Marshall’s – expansive reading of the federal commerce power.

An admirer of Thomas Jefferson, Emmet was often engaged in party battles with the Federalists. His Federalist opponents comparing him to a snake, called him “Thomas Adder Emmet.” His first case in an American court was a defense of a fugitive slave, and he remained active in the anti-slavery cause. But he did not have an altogether immaculate liberal record.

When it came to wage slavery, he sided with the employers. In a case involving journeymen shoemakers organizing for higher wages, Emmet argued that they had no right to form a union. In a letter to a friend in Ireland, he complained of what he called “the most crying grievance of America, the badness of servants, of which, and the enormity of wages, you can scarcely form an idea.” His pamphlet of 1816, “Hints to Immigrants,” urged newcomers to behave properly and seek respectability.

Emmet was known for having the most “sarcastic humor” of the American bar. Justice Story called him “the favorite counselor of New York.” David A. Wilson, the historian of the United Irishmen in the United States, wrote that Thomas Addis Emmet “became the most respected Irish American of his generation.”

If the United Irishmen owed something to the United States, the United States owed a great deal to the United Irishmen. More than 2,000 United Irishmen settled in the United States. Emmet; the physician William James MacNeven; Edward Hudson, a pioneer in dental surgery; the lawyer William Sampson; the mathematician Robert Adrain; the horticulturist Bernard McMahon; the architect John Neilson; and the journalist John Daly Burk all left their mark on the infant republic.

The United Irishmen brought more than individual accomplishments. They brought a passionate commitment to a non-sectarian democratic republic based on personal freedom and social justice. They called for a broader political franchise, liberalized naturalization laws, freedom of worship, and reform of the legal system. They also brought political talents and skills that energized the embryonic American democracy. As David Wilson wrote, they “made Irishness synonymous with radical republicanism.”

A Federalist congressman from Pennsylvania observed, after traveling around the stale during the election of 1800, “I have seen many, very many Irishmen, and with a very few exceptions, they are United Irishmen, Free Masons, and the most God-provoking Democrats on this side of Hell.” United Irishmen helped lay the foundation for the election in 1828 of the first Irish president, Andrew Jackson, whose parents came from Carrickfergus in County Antrim.

(I would like to think that descendants of the United Irishmen, as the progeny of notorious rebels and revolutionaries, have remained faithful to the radical politics of their ancestors.)

It was two centuries from the defeat of the United Irishmen in 1798 to the achievement of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The accord – that promises at last to end years of insensate violence and prepare the way for an Ireland united, if not in sovereignty, at least in cooperation, religious tolerance and peace – is very much line with the principles of 1798. ♦

Read also an Irish Patriot Remembered by Patricia Harty.

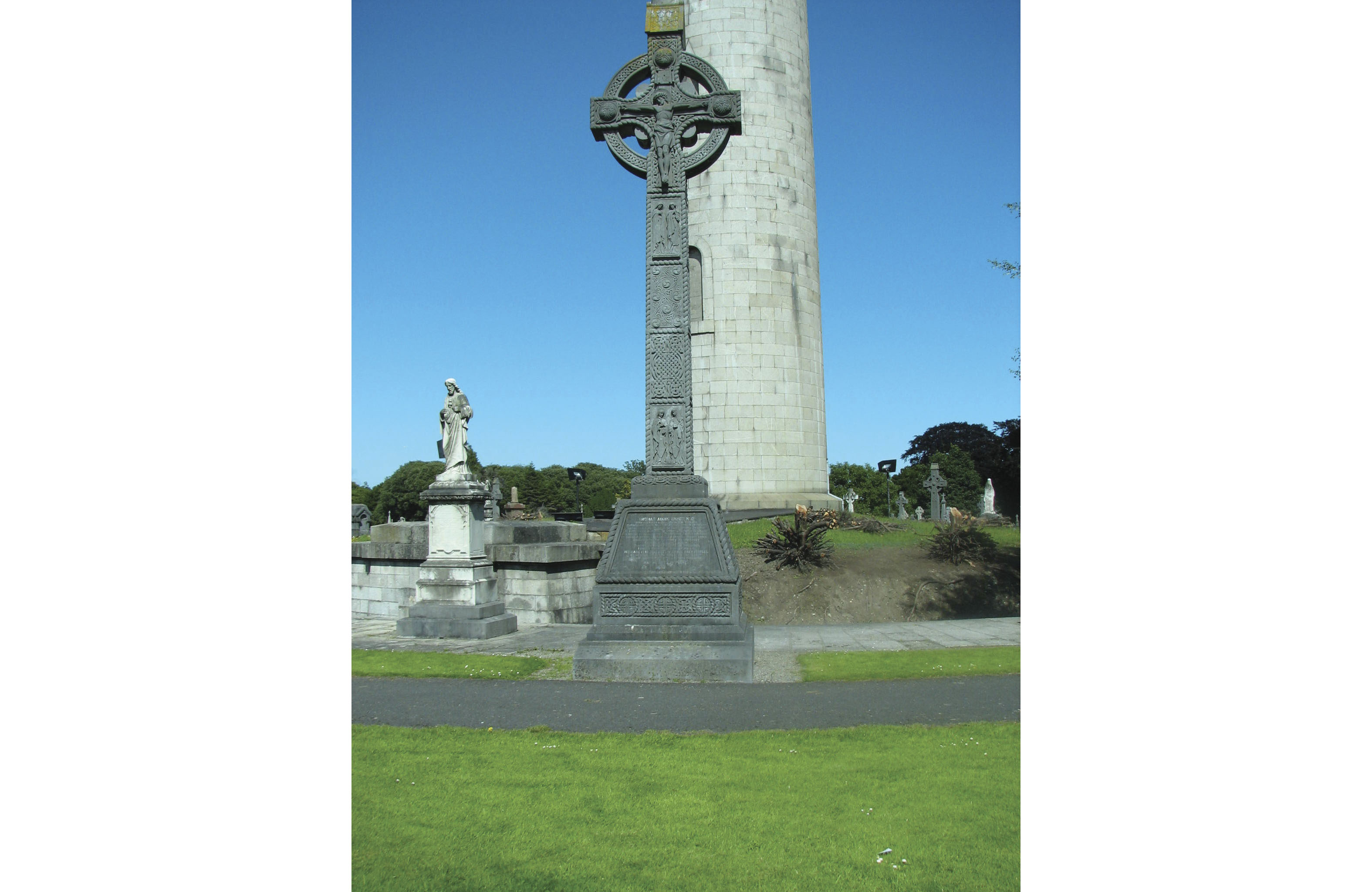

Thomas Addis Emmet died in 1827 and was buried in St Mark’s-in-the-Bowery Churchyard in the East Village, New York City. His grandson, Dr Thomas Addis Emmet, a prominent doctor and Irish American activist, had him reburied in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the final resting place of many of Ireland’s patriots.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., a historian and social critic, was a special assistant to President Kennedy. Married to Alexandra Emmett, he specialized in 20th century American liberalism and authored, among other works, A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. This article originally appeared in the April / May 1999 issue of Irish America. He died in 2007.

Hello,

I would like to have further information about Thomas Emmet and other United irishmen in the U.S.A.

I’m married with one descendent from John Swiney – an United irishmen very close to Robert Emmet that told him that Thomas A. Emmet was death. Swiney settled in France around 1803 but misteriously went to New York around 1807 and came back to France. Why? No idea lol. But I’m working on my family history to understand better our irish roots.

My family are historically connected with yours.

For me, it’s a good idea to keep in touch.

Kind regards,

Denize Swiney

May I point you to this article:

“The significance of the July 4 online discussion, “The Place of the Two American Revolutions: Past, Present and Future”

https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/07/06/pers-j06.html

My great great grandfather was a Douds, do not know first name, who was an officer in the Unitd Irishman’s rebellion of 1798. He later came to Canada and on into Crawford County in PA. Any info you have that might help me recreate this time period in our family history would be welcomed. The family was from County Down.

13th September 2023 will make a special day as I present a talk on The Priory Ruins, in Rathfarnham. This was the home of John Philpot Curran and his daughter Sarah Curran who was the lover of Robert Emmet. After many years of leading a campaign to get South Dublin County Council to maintain the ruins of the original house, this is now completed with a beautiful plaque which memorialises the death of little Gertrude who died aged 12 and is today buried on the green. LEST WE FORGET