David Neligan, a member of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, acted as a valuable agent for Michael Collins by passing on vital information during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21). He subsequently became Director of Intelligence for the Irish Army after the Irish Civil War (1922–23).

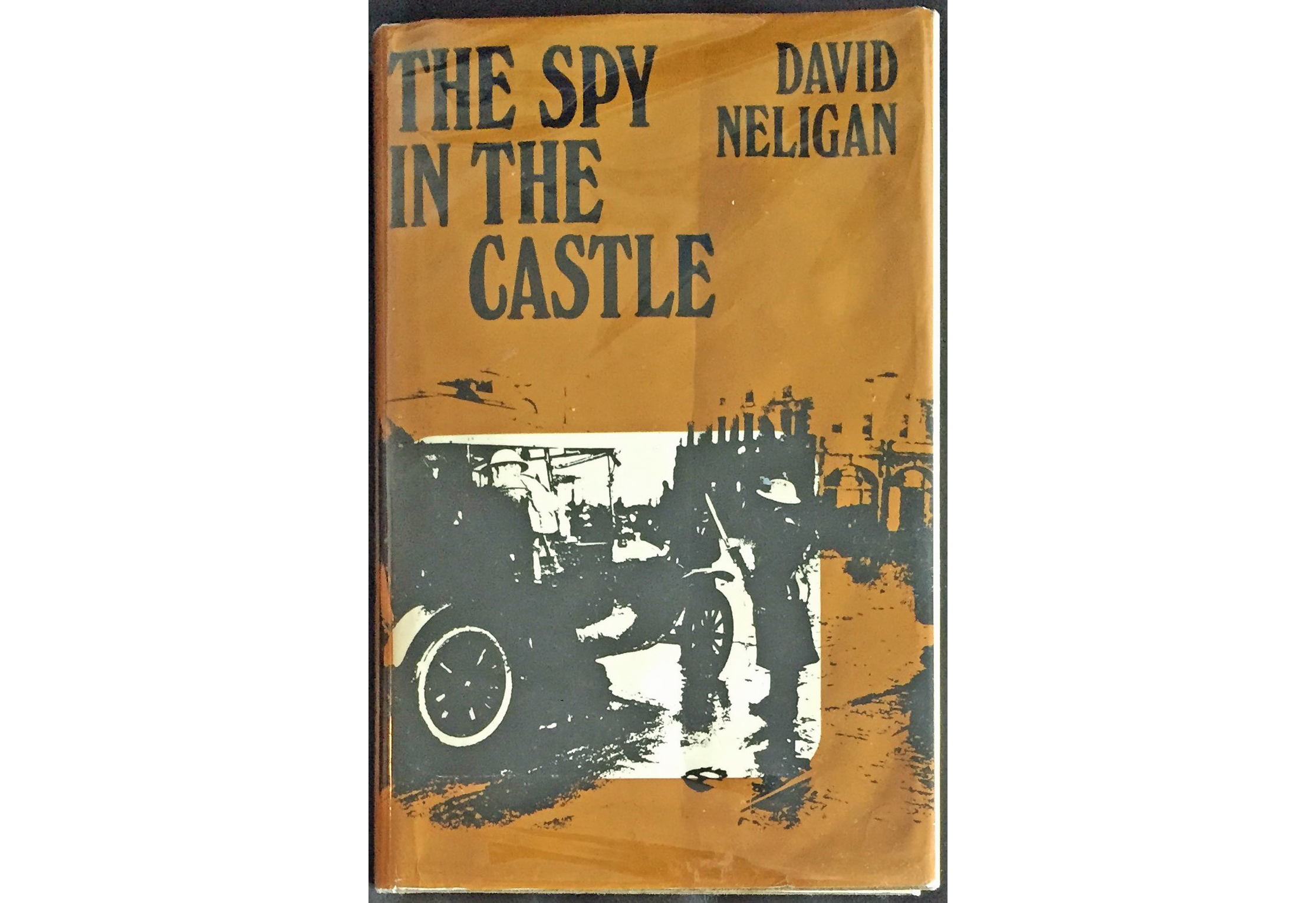

I’m sheepish to admit that I only came to learn of David Neligan through self-interest. Chasing trans-Atlantic cousins in my genealogical quest some years ago, I reached out to renowned heart surgeon and medical pioneer, Maurice Neligan, about our Neligan lines that both led back to the village of Duagh in Co. Kerry. Dr. Neligan was kind enough to swap emails with me and it was he who suggested I read The Spy in the Castle, a book written by and about his uncle, David Neligan. The castle referred in the title is Dublin Castle, which was the United Kingdom’s administrative headquarters and the heart of British espionage in Ireland until 1922.

You probably haven’t heard of David Neligan, but there’s a good chance that you’re familiar with his derring-do. If you’ve ever watched the epic biopic Michael Collins, starring Liam Neeson (whose son, Micheál Neeson, is slated to take on the same role in the upcoming film, The Rising), you may recall a double-agent, Ned Broy, who was portrayed by Stephen Rea. Eamonn “Ned” Broy was real enough, but in the interest of simplifying the story of the Irish War of Independence for audiences around the globe, director and screenwriter, Neil Jordan, took some liberties – one of which was distilling the activities of several spies (Broy, Neligan, James McNamara, and Joe Kavanagh) into the life of this one character. So some of what happens to “Broy” in the film was actually Neligan’s experience, and some of what he accomplished is left out.

Still, when you consider that between 1918 and 1923, Neligan alone served as a policeman with the Dublin Metropolitan Police, a G-Man (a member of the wing of the police department’s G Division devoted to political subversive movements), a Volunteer, an I.R.A. Intelligence Officer, a British Secret Service agent (startling even Collins with his audacity in securing this position in early 1921), a National Army Intelligence Officer, and founded An Garda Síochána (the Irish Police), there’s ample reason for streamlining people and events when trying to convey the whole of the saga. And that’s part of what makes Neligan’s story so compelling.

Aught Actuated by Malice

Written in his later, more mellow and introspective years (he was nearing 70 when it was published), The Spy in the Castle gives the reader a backstage pass to dramatic events many thought they knew so well, but in a voice gently tinged with regret. I was intrigued as soon as I read the opening words: “This is the story of my service with Michael Collins at the time of the Black and Tans. Everything set down is true, nothing has been exaggerated nor aught actuated by malice. To protect innocent people, I have transposed some names and incidents without damaging the truth. Descendants of some persons mentioned live and I have no desire to embarrass them or cause them pain.”

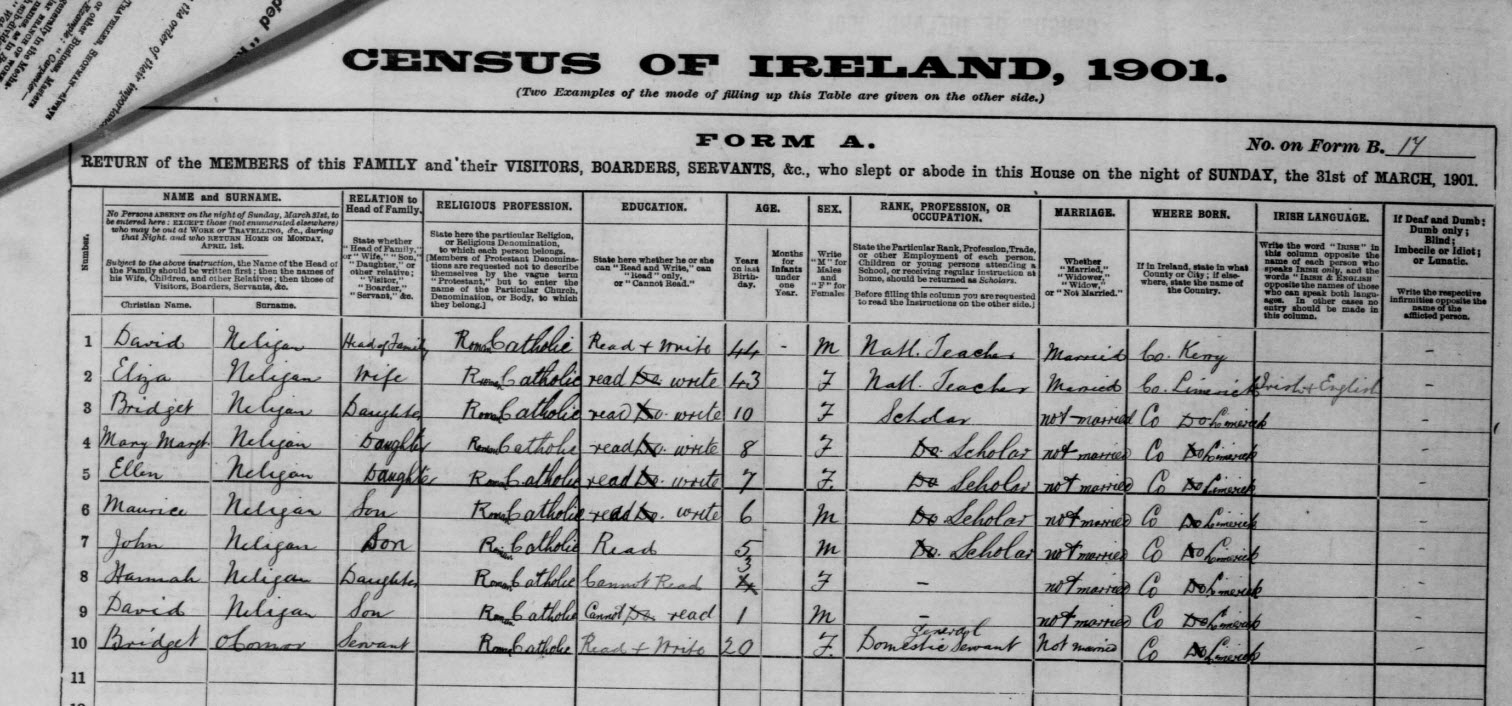

Neligan was born in Templeglantine, Co. Limerick, in 1899, to a pair of school teachers. He spends several chapters reminiscing about his countryside childhood as the youngest of eight, and takes time to share antics or favorite turns of phrase of long-passed locals, which makes it harder to reconcile this grandfatherly quality with the matter-of-fact tone taken as he later succinctly records the deaths of so many he knew personally. Even so, twinges of conscience emerge about a few individuals whom he had respected but deceived, or worse yet, were essentially collateral damage.

Policing was a well-trodden path for rural young men at the time who sported a bit of ambition. It’s what brought him to Dublin, but beyond that, his slipping into a revolutionary role seems almost accidental. Raised on a diet of fictional spies like James Bond and Jason Bourne, one can’t help but marvel at how ordinary Neligan was. And yet, in real life – in genuine espionage – isn’t that what makes an extraordinary spy? He was so nondescript that he passed the entire Irish War of Independence undetected by the British, even while working in the midst of their intelligence operations and routinely meeting Collins – a man for whom he never lost his immense admiration. Indeed, it seems that his total belief in Collins was the source of most of his motivation, conviction, and courage.

To impart a flavor of Neligan, I have his book and want to share a number of quotes and excerpts. While I could recount everything myself, doing so would diminish these vignettes, as his way of telling the tale is one of the best and most revealing aspects of his story.

The Spy Who Almost Wasn’t

One of Neligan’s more striking anecdotes is how he came to work with Collins in the first place. Those who have seen the Jordan movie may remember a scene where Collins, fresh out of prison and picked up at a train station by associates, asks how the G-Men who were waiting for him knew he was coming. He’s told, “They know what we eat for breakfast.” To which he responds, “There’s only one way to beat them then. Find out what they eat for breakfast.” In short, he aimed to outwit the British at their own game, and using what he learned, he put the fear in would-be traitors by killing known collaborators and dried up the pool of potential informants used by the British. To do this, Collins was interested in a wide range of sources, but especially those in a position to serve as double agents.

Neligan had become a G-Man in the autumn of 1919. As he explains, “I applied and was accepted. This was due to no merit on my part as the shootings had made this service unpopular with the general run of the force. In peace times it was difficult to get in but now the opposite was the case. The Castle was faced with a tough situation. Never before had such a determined and lethal attack been made on the British intelligence forces nor one directed with such ruthless efficiency.”

The following year, he approached Paddy Sheehan (a man with whom he had hometown connections), who was on the Dáil staff, and sometimes served as private secretary to Éamon de Valera, to offer his services. According to Neligan, “Sheehan promised to enquire, returned and advised me to resign,” which he did in May of 1920. But shortly thereafter, “A man named Tim Kennedy… told me that Collins wanted to see me, and he wanted me to go back to the G Division to work for him…I suggested to Kennedy that he should arrange for a few threatening letters to be sent to me at home in Limerick, ordering me to clear out, and I could show them to the Castle people. These duly arrived. Curiously enough they were the only samples I’ve ever received, though sending them is a pastime in Ireland. It appeared that Sheehan, who belonged then to the political wing of Sinn Féin, had not realized the implications of my offer. Collins was annoyed that he had not been told.”

It was soon after this that he first met Collins in Dublin: “A tall, handsome man of about thirty who was alone arose from his chair and greeted us… He was about six feet tall. Sturdily built, athletic, broad-shouldered, with a winning smile, a ready laugh and cheerful manner. He had a trick of turning his head swiftly and then the resolute line of his jaw showed. He was a friendly man with the fortunate manners of putting one at ease. He was dressed in an ill-fitting tweed suit which had cycling clips on the pants… Shaking my hand with a firm grip, he said: ‘I know you and your brothers are all right (i.e. friendly to the revolution) – it is too bad about Moss’s death (note: he was referring to David’s brother, Maurice, who had recently died in a motorcycle accident). You shouldn’t have been let resign – there was a misunderstanding. I want you to go back to the castle to work for us.’”

Neligan was reluctant, but allowed himself to be persuaded by Collins when he said, “Listen, Dave, we have plenty of men for columns, but on the other hand no one can fill your place in the castle, for they trust you and we trust you.”

Equipped with the menacing letters he had requested, Neligan was able to get back into the G Division and was soon passing critical intelligence to Collins. It was Neligan, for instance, who told Collins about Alan Bell who was investigating how the revolutionaries were funding their operations. The moment he did so, Bell’s days were numbered.

Collins and the Humble Folk

A theme Neligan often returns to in his book is Collins and his connection with the Irish people. He refers to his “great personal magnetism and generosity,” saying that, “If anyone were ill, depressed or lonely, one person never forgot: Michael Collins… At Christmas time he had Joe O’Reilly run off his feet buying presents for everyone. He gave me a silver cigarette case wrapped in tissue papers. Others got tobacco, cuff-links or some other little gift. In the middle of his myriad tasks, he did not forget these little touches which endeared him to all.”

Neligan also mentions the contributions of specific, under-the-radar individuals who took significant risks, such as the fellow who hosted the weekly sessions Collins had with his double agents: “Broy, McNamara and myself used to meet Collins once a week in the house of Tommy Gay, 8 Haddon Road, Clontarf. This was a quiet, suburban place, several miles from the city. Gay, a tiny Dublin man, with bronchial trouble which made his life a burden, was librarian in Capel Street Municipal Library. Like nearly all the dramatis personae of the revolution, he led a double life; a bookworm openly and also, secretly, a confidential courier for Collins. He was so unobtrusive that neither the library nor his home ever came under suspicion. He and his charming wife were the soul of discretion. Such people were a Godsend to Collins.”

Neligan makes it clear that people like the Gays were key to the revolution: “Waiters, hotel porters, and other humble folk knew Collins, Tobin, Cullen, and other leaders. They never breathed a word whereas they could have commanded a fortune by betraying them. No monument exists to such people. They are never mentioned. History ignores them. They got no pensions, no medals, and no thanks. To my mind they are the most deserving of praise, who by their loyalty and devotion defeated every effort of the enemy. The sort of guerilla struggle that went on in Ireland depends, of course, on the active support of the populace. Where this is not forthcoming, defeat for the weaker side is inevitable.”

Memorable Moments

As one might expect of anyone who was a double agent, Neligan has a number of colorful episodes to share – often a blend of enlightening, scary, and humorous. For example, he details one of the close encounters Collins sporadically had with the British – this one shortly after he and the G-men had finished one of their meetings at Gay’s house. Though Collins generally traveled by bike, he had a tight schedule that night, so a taxi driven by a trusted friend arrived to pick him up, and Collins offered the others a ride back into Dublin. They had only gone about half a mile when, “We were held up by a squad of Tommies across the road. Collins jumped out, suspecting a trap, but we persuaded him to come back in. An English officer came over and asked us who we were. We answered that we were detectives looking for Collins. He said, ‘By Jove, that explains it! Those blighters were waiting for you. They’ve just thrown a bomb at us! If I were you, I’d go back and return some other way.’”

And then there was the time that Neligan was struck by the strangeness of his guarding the Dáil: “The proscribed Dáil or Sinn Féin Parliament, most of whose members were ‘on the run’, was to hold a clandestine meeting in Dublin… Collins asked me to keep a sharp look-out against Castle agents in the vicinity of the meeting… The session lasted two or three days. So I took leave for that period and spent each day patrolling in the vicinity, but saw no suspicious touts about. Truly, truth is stranger than fiction! Here was I, a member of the Castle political police, keeping watch over the rebel parliament, at the behest of Michael Collins, the most hunted man in Ireland… This Dáil which I protected, contained men who afterwards persecuted me and made my life a misery. Such are the turns of fortune’s wheel.”

Yet another instance concerns what actually happened to Ned Broy. He was captured as seen in the film, but not killed (the true Broy living until 1972). Neligan tells how his life was saved: “It was freely rumoured that Broy was to be executed. In the temper of the enemy at the time, it was a distinct possibility. McNamara and I met Collins in Gay’s house… He (Collins) told us he would organize his rescue; the odds meant nothing to him; he revelled in forlorn hopes. … Knowing what his reaction to Broy’s arrest would be, I had been … sizing up the possibilities.” Neligan spelled out the specifics and concluded with, “Anyone who shows his nose near that place will be chatting with his forebears in seconds.” Collins horrified, asked, “What’ll we do so?”

McNamara and Neligan recommended intimidating the man most likely to be assigned to prosecute Broy. They knew him to be the impressionable sort so, “We told Collins to have it conveyed to him that if he went on with the case, the best thing he could do was to pick out a nice shady spot for himself in Mount Jerome Cemetery (coincidentally, where Neligan would eventually be buried in 1983)… Collins was delighted. ‘By God,’ he said, ‘I’ll go up there tonight!’ This meant a ride on the old bicycle of at least ten miles and he cleared off at once.” Neligan further relates that the message was delivered and the recipient cleverly protected himself by informing his superior that both of their lives were at risk. Soon after, the materials that could have been used against Broy were conveniently burned.

Regrets, I’ve Had a Few . . .

In May 1921, Neligan proposed to Collins that he join the British secret service. Collins didn’t initially believe it would be possible, but was excited at the prospect. “Begod,” he said, “if you did it would be wonderful.” Using a cover story that he was fed up with being harassed by Sinn Féiners and that he simply needed more money, Neligan was able to get in. In this capacity, he continued to serve Collins while working with the British secret service. And for reasons he never learned, he was even sent to England during treaty negotiations so that he happened to trip across Collins the very day the “Shinners” were celebrating signing the treaty on the way home.

According the Neligan, on that occasion, “Tobin said, ‘We’ll have to face our die-hards now,’ the first time I’d heard the expression used in Irish politics. We were to hear it often enough afterwards!”

In that remark are the seeds of his later wistfulness. Though the book ends before his controversial career as Director of Intelligence for the National Army during the Irish Civil War and Head of Special Branch of the Garda Síochána, he laments that, “A wonderful spirit of comradeship existed in those terrible days, but sorry I am to say that it did not survive the Truce. Instead we had selfishness, jealousy, and a large number of swollen heads. It is quite true, of course, that the character of some of our best men did not deteriorate, but those who were meant by nature to be small showed their true form; they could not stand success, which to some is more damaging than failure.”

Lest there be any lingering doubt about Neligan’s frame of mind in his later years, he concluded, “If anyone asked me was it worth while; would I go through it again: I should answer No. Certainly I do not regret, and shall always look back with affection on my friendship with Michael Collins whose terrific ability and dynamic energy ended so pitiably with a bullet through the head on the side of the road… It was well said: Revolution devours her own children.” ♦

_______________

Megan Smolenyak is a genealogist and the author of six books, including Trace Your Roots with DNA and Who Do You Think You Are?, a companion to the TV series. She prefers to call herself an incurable genealogist and sometimes author.

Megan

I wanted to ask if you had written the article on David Nelligan and if so what is your Nelliganrelationship.

This is part of my family tree.

Regards

Eoin

I am David Neligan’s daughter , what is your Neligan relationship?

Nice summary. Just ordered the book to read. David spent a number of nights with my grandfather and wife in Athy. Grandfather was Thomas Flood, was captain in burning down the Custom House 1921. David never forgot my grandfather’s role.

i am trying to trace a possible second book by David Neligan

I met a lady in kells who lived near navan and said she was a daughter of David neligan and mentioned an unpublished manuscript

there are aspects of Neligan’s activities among teh secret Service that i would like to hear about

Tim Pat Coogan seems to have interviews him and mentioned a n agent tailing David whh\o shot his tail off Merrion square – that seems to be Purcell Rees Bowan

there is also a mention of an agent killed in dublin mountains which might be Montagu de Belabre

I am author of Murder by the Throat, a study of spying informing and collaboration during the War of Independence

have you ever thought of writing a book about your father?