Today world news is immediate but 100 years ago transmission depended on telegraph cables under the Atlantic ocean that were subject to wartime and censorship conditions.

℘℘℘

In April 1916, the front pages of America’s newspapers were dominated by headlines about the war on Europe’s western front, where the German and French armies were battling at Verdun, and by reports of German American opposition to President Wilson’s re-election campaign. Then, on Tuesday morning, the 25th, came news of the capture of a German ship that had tried to land arms on Ireland’s west coast, and the arrest of Sir Roger Casement, a retired diplomat. “Daring Invasion of Ireland by Germans Fails,” screamed the Charlotte Observer in North Carolina. Partisan passions about World War I were running high in the United States, and pro-British papers like The New York Times were quick to circulate the “official” announcement calling Casement “mentally unbalanced,” and the Irish news nothing more than a “madcap adventure.”

The afternoon and evening papers that same day brought the first word of unrest in Dublin: a statement released by Augustine Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland. This was rapidly distributed by the newswires and picked up as far west as San Diego. The Easter Rising was called “a grave disturbance” initiated by “rioters” that “was now well in hand.” The Brooklyn Eagle quoted Matthew Keating, the Irish member of Parliament for South Kilkenny, who called it “an act of folly by political lunatics – old disgruntled cranks and young Sinn Féiners.”

When the Irish writer Mary Colum (who moved to New York in 1914 with her husband, the poet Padraic Colum) opened her newspaper over breakfast in a New York City boardinghouse on the 26th, she “saw that what we knew was going to happen had happened – the Irish once more had taken up arms in a fight for independence; the leaders had seized government buildings and railway stations; the fight was on, the fight Pearse and others had so often spoken of, similar to those our ancestors had vainly engaged in…Tremblingly I looked up; everyone seemed to be talking of the happening.”

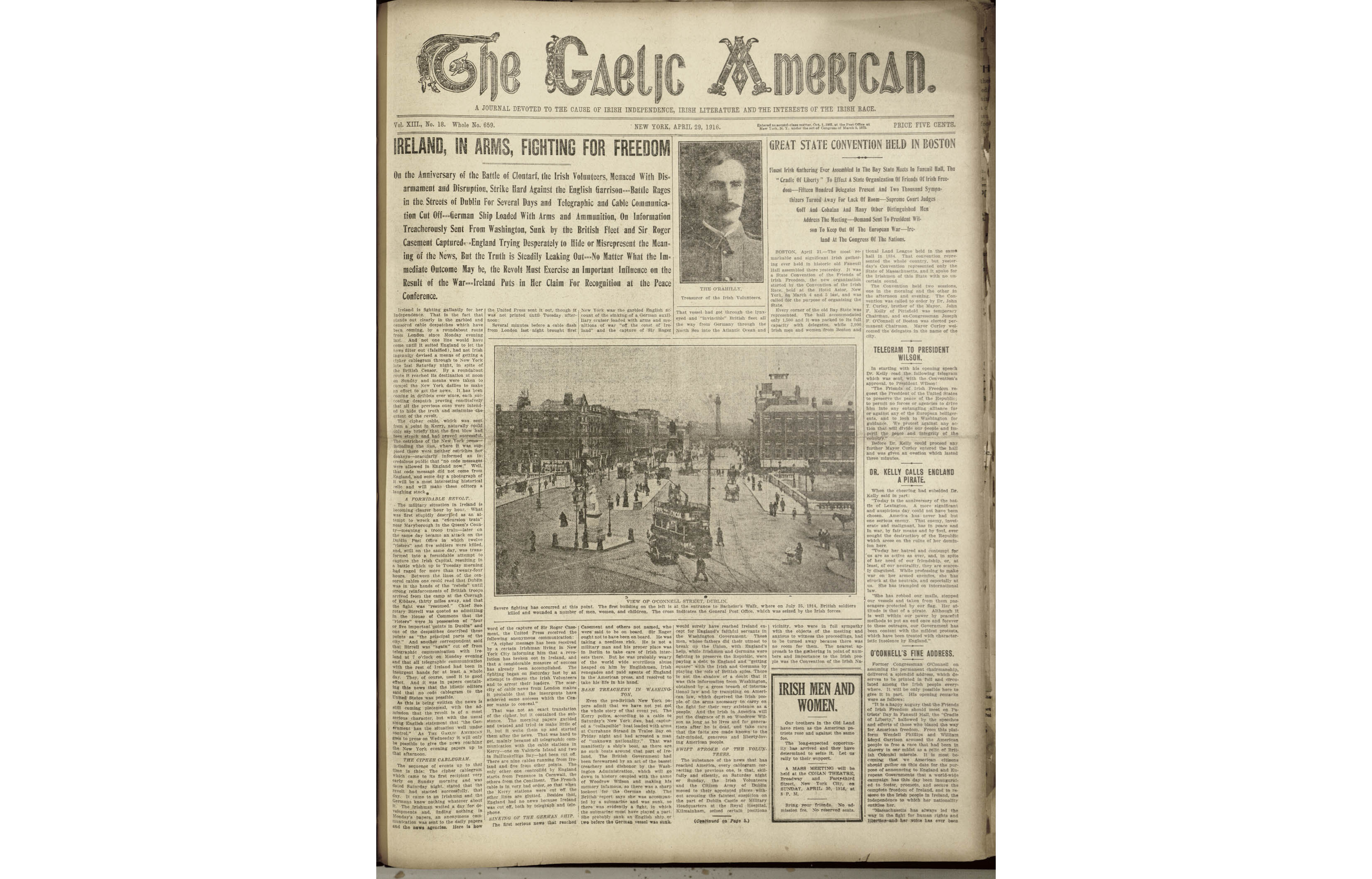

Only a handful of Irish Americans had known of the secret plans for insurrection. One of them was John Devoy. A republican legend in his own time, and considered one of Britain’s most dangerous enemies, the 74-year-old Devoy was the editor of the weekly Gaelic American. It had a national circulation of 28,000 and had all but announced the Rising in its March 11th edition. The annual Emmet commemoration, it intimated, “may be the last of its kind that will be celebrated by the Irish people of New York before the patriot’s epitaph is written. Before March, 1917, the British Empire may have gone the way of Assyria, Greece and Rome.”

On Easter Sunday 1916, Devoy received a cipher cablegram sent the previous evening from Valentia, Co. Kerry, to “a certain Irishman in New York.” It was the pre-arranged signal that the Rising was about to start. But when there was no news of it in the city papers on the morning of April 24th, Devoy sent an anonymous message to the United Press wire service announcing that a revolution had broken out in Ireland. “The scarcity of cable news from London,” it said, “makes it probable that the insurgents have achieved some success which the Censor wants to conceal.”

Devoy suspected that all news sourced from Westminster or Reuters that Easter week was intended “to hide the truth and minimize the extent of the revolt.” On the 28th, Jeremiah O’Leary of the American Truth Society leaked key details to the Associated Press to balance stories datelined London: there were 10,000 rebels and $100,000 had been contributed by Irish Americans towards the Rising.

When the next issue of the Gaelic American was published on April 29th, Devoy showed that he could play the propaganda game as well as Birrell: “Ireland is fighting gallantly for her independence… skillfully and silently, on Saturday night or Sunday, the Irish Volunteers and the Citizen Army of Dublin moved to their appointed places without arousing the faintest suspicion on the part of Dublin Castle or Military Headquarters at the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham.” Although Devoy didn’t yet know that the Rising had been postponed until Monday, he confidently declared, “The Irish Volunteers have struck a blow that has echoed round the world and produced a situation that will exert a considerable influence on the result of the war.”

The Irish World reported the facts as they stood at press time: twelve lives had been lost in 24 hours of fighting, and the insurgents held four to five positions in Dublin. Except for this brief article on page one with the headline “IRELAND IS IN ARMS,” the Irish World continued its usual weekly coverage of developments of interest to Irish Americans. But its editor gave a revealing statement to the New York Herald Tribune: “I can’t see how any Irishman can help rejoicing that the insurrection is under way or can help hoping for its success.”

Many of the large circulation dailies favored the Allies. They saw the Rising as high treason and Casement as nothing less than a traitor in a time of national emergency. Although officially neutral, the United States’ economy was benefiting from immense munitions sales to Great Britain, and President Wilson urged American preparedness for war. Paranoia increased about anyone perceived to be less than 100% American.

In this context, the mass meeting called in the name of the United Irish Societies of America at New York’s George M. Cohan Theatre on April 30th was particularly troubling. Three thousand people crammed inside to express sympathy for Ireland, while the police estimated that 15,000 jostled outside. The New York Times, which covered Easter Week and its aftermath for 14 consecutive days, reported that the crowd gathered to “voice their approval of the present uprising in Ireland, to sing the songs of Germany as well as Ireland, to denounce John Redmond as a traitor, to cheer a reference to the sinking of the ‘munitions ship Lusitania,’ to pass a resolution urging the recognition of the belligerency of Ireland and the linking of the Emerald Isle to the Teutonic powers as a military ally, and to compare Sir Roger Casement to George Washington.”

Undercurrents of disapproval regarding the Rising were not unique to the Times. Opinions on the course of the war in Europe prompted reactions like that of John Quinn, a New York lawyer and supporter of Home Rule who said, “I have been disgusted and depressed by the horrible fiasco in Ireland…the whole thing was sheer lunacy.” Weighing the realistic probabilities of success, John Devoy calmly predicted at the Cohan Theatre that “no matter how many leaders are shot or hanged new men will spring up and take their places and the fight will be fought to a finish. The effect on the Irish race abroad is already splendid.” He did not know, as he spoke in New York on Sunday, that the leaders in Dublin had conceded their fight the day before.

By that time the wire services had correspondents on the ground in Dublin and the first descriptions of the extensive destruction there appeared. News of Pádraig Pearse’s surrender was not reported in American newspapers until Monday, May 1st, along with the first accounts that an Irish Republic had been declared. The Springfield Daily News in Massachusetts described how dramatically Pearse came down the steps of the General Post Office on the 24th, “attired in some fantastic uniform with golden tassels and sword,” to read the Proclamation from the center of the tramlines in Sackville Street. The Atlanta Constitution printed its text in full. The speed with which updates were being published inevitably led to some mistakes. The Washington Post suspected that radical labor leader Jim Larkin was “one of the ringleaders” of the rebellion. Five days after, Larkin, reached by telephone at his Chicago home on the 29th, told the New York Times, “I have nothing to say on the Irish situation.”

The daily papers got word of the executions first. “On a May morning, a fair sunny day, as I got off the subway at Grand Central,” Mary Colum remembered about May 4th, “I saw the headlines of the early afternoon papers. Pearse, MacDonagh, and Clarke executed. I must have sat for long in the waiting room in a dream or a semicoma, for when I looked at the station clock it was late in the afternoon … Day by day the roll of the executed continued, a few each day… The names of the leaders stared out at us from the paper, the young men I had worked with, had danced with, had read poetry with…”

The United Irish League chapter in New York cabled John Redmond, the senior Irish politician in Parliament, “Irish in America, contrasting execution of Dublin leaders with treatment in Ulster and South Africa, are revolted by this sign of reversion to savage repression.” Robert Ford of the Irish World issued a statement to the press that was widely reproduced: “Pearse was a prisoner of war and should have been treated as such…like Washington, [he] represented a people throwing off the yoke of England.” Revulsion at the turn of events even prompted a New York Times editorial on May 5th that said Britain’s biggest mistake was not shooting Birrell, who had resigned the day before.

The next edition of both Irish American papers hit newsstands on May 6th. The Irish World firmly fixed the 1916 uprising in the republican canon under the headline, “The Young Men Who Are Sacrificing Their Lives Today on the Altar of Their Country Will Go Into the Irish Nation’s Valhalla Along with Wolfe Tone, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Robert Emmet, Allen, Larkin, O’Brien, and the Other Patriots Who on Rack and Gibbet Have Died That Irish Nationality Might Live.”

The Gaelic American remained optimistic. “FIERCEST BATTLE EVER FOUGHT IN IRELAND ENDS IN TEMPORARY DEFEAT…GERMAN HELP WILL COME LATER AND BRING FINAL VICTORY,” declared a long subhead. Devoy reminded readers of the number of Irish who were at that very moment facing death on European battlegrounds: “The renegades and fools who talk of the terrible sacrifice of life in Dublin which has brought the renovation of Ireland’s military credit are quite satisfied with the rivers of Irish blood shed for England without a single benefit for Ireland.”

In a news world so completely dependent upon transatlantic cables, the decision by Pearse and his team to occupy the G.P.O., the center of communications in Ireland, and cut its telegraph wires was not only strategic but allowed them to seize the public relations advantage. Likewise, Irish American leaders knew the value of publicity and within a fortnight of the Easter Rising there were sympathetic demonstrations all over the United States that were reported in local print media. Outraged by the executions of fifteen men and the imprisonment of hundreds of Irish nationalists in Wales, membership in the new Friends of Irish Freedom soared. For the rest of the war, Irish Americans strategically deployed the rhetoric of “small nations” and “self-determination” to connect the settlement of WWI with freedom for Ireland. American journalists, editors, and publishers would not be allowed to forget the Irish Republic of 1916. ♦

_______________

Marion R. Casey is a clinical assistant professor of Irish studies at NYU as well as the senior archivist for the Archives of Irish America. Most recently, she is the editor of the forthcoming Religious Freedom: Bicentennial Reflections on People v. Philips (Fordham UP).

Leave a Reply