As World War I loomed, the U.S. was wracked by political, ethnic, and religious tension. Most Americans hoped to remain neutral, but the Irish in the U.S. were not shy about whom to root for.

“The German guns will be the call of Ireland to her scattered sons,” Roger Casement wrote in his tract, “The Crime Against Ireland and How the War May Right It.” “Let Irishmen in America stand ready, armed, keen, and alert.”

When German spies flooded the States, they looked in New York’s docks to find allies. One German spy noted that, “many of the stevedores were Irish, and when he heard them openly snarling about having to load a ship flying the Union Jack [this] was a visceral hatred he would exploit,” historian Howard Blum writes in Dark Invasion, about Germany’s secret war in the U.S.

Being co-opted to help German spies put Irish Americans at odds with the mainstream of U.S. society, which – though technically neutral on the war question – generally favored the British with whom the U.S. had a valuable business relationship.

And while Irish American wartime sympathies may have been ignored at first, the Fenians’ reliance on Germany while plotting the Rising would eventually provoke hostility, harsh words from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, and even charges of treason by U.S. authorities.

Planning the Rising

Getting German support was an important issue for John Devoy, who, according to Terry Golway in his biography, Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America’s Fight for Ireland’s Freedom, spent much of the “winter of 1914 and the whole of 1915 … in constant touch with the German consulate on Wall Street.”

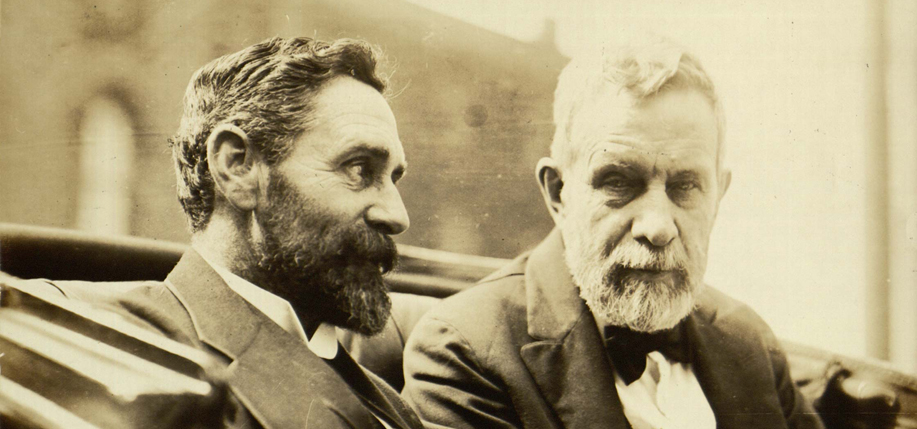

Roger Casement arrived in New York City in July 1914, just weeks after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo plunged Europe into the chaos and carnage of World War I. “Casement had … assessed the impact of conflict in Europe, [and] deliberated on its potential effect regarding Irish independence and the role of Irish Americans in the war,” writes Ross J. Wilson in New York and the First World War.

“The machinations of Casement and Devoy in New York placed the city directly into the struggles that were taking place in Europe. Indeed, Casement actively sought the support – financial, moral, and physical – of New York’s Irish American residents in the struggle for freedom against the British Empire.”

Late in 1915, Devoy also hosted Joseph Plunkett, one of the Easter Rising leaders, in New York, where they planned a meeting with German military officials.

At the same time, Devoy was also meeting influential Irish Americans, including lawyer Jeremiah O’Leary, a founding member of the American Truth Society, a group of “Irish and German emigres,” who, according to Wilson’s account, wanted to “disrupt any Anglo-American alliance” and “expose the machinations of Britain towards the United States.”

Flexing its muscle, The American Truth Society publicly slammed the anglophile Woodrow Wilson, who disdained what he called “hyphenated Americans.”

“I would feel deeply mortified to have you or anybody like you vote for me,” President Wilson thundered back at O’Leary. “Since you have access to many disloyal Americans and I have not, I will ask you to convey this message to them.”

The Battle

It was in such a heated atmosphere that in February 1916, Devoy was given the proposed time of the Rising, and told in a coded message, “We must have your arms and munitions in Limerick between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. We expect German help immediately after beginning action.”

A month later, at the third Irish Race Convention in New York City, Devoy formed The Friends of Irish Freedom to build support, but even as events were about to explode, grew suspicious he was under government surveillance. He was right – he was – and in April 1915 he was served with a subpoena at his newspaper, The Gaelic American, to appear before a grand jury investigating pro-German activities in the U.S.

At the same time, Irish rebels and Germans were running guns from Germany and the U.S. to Ireland. They loaded twenty thousand rifles, and a million rounds of ammunition, onto the Aud, and set sail from Lubeck, Germany. British authorities spotted the vessel and, after the crew failed to evade a British gunship, they scuttled the ship rather than allow the collusion by American, Irish, and German citizens to be exposed.

The day after the Rising began, The New York Times reported only on the arrest of Roger Casement. (He had arrived by German U-Boat and having been put ashore on Banna Strand in County Kerry in the early hours of April 21, was soon captured.) On Wednesday, April 26, a three-column, front-page report noted that, “Troops Crush Revolt in Dublin; Take Post Office Seized by Rioters; Many Killed in Street Fighting.”

The Times, and the majority of the U.S. mainstream media, took a pro-British angle on the news coming out of Dublin, with the The New York Herald, for instance, characterizing the rebels as “Pro-German propagandists.” Devoy wrote impassioned defenses of the rebellion in The Gaelic American, and, on April 30, a subdued rally was held in support of the rebels and what was by then considered a failed insurrection at the Cohan Theater in Manhattan.

In the weeks that followed however, attitudes changed. First came news that Britain had executed Pádraig Pearse, Tom Clarke, and Thomas McDonough, and the swiftness of that retaliation shocked the world. Newspaper editorials protested the action. Then, days after James Connolly was executed on May 12, more than 20,000 people gathered in and around Carnegie Hall in a massive act of protest.

The War, the Legacy

The U.S. entered the war fighting alongside the British in 1917, and that led to a crackdown at home on what were considered “radical opinions,” and the Irish in America became prominent targets.

Newspapers and magazines, including Devoy’s Gaelic American, as well as the Jesuit journal of opinion, America, were banned. Many Irish American nationalists were accused of treason – some even indicted – based on their alleged dealings with the enemy, Germany.

Despite the persecution, the bonds between Ireland and America remained strong. In February 1919, with the world war finally over, another Irish Race convention was held in Philadelphia and the highlight was a speech by James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore in which he declared, “All Americans should stand as one, for Ireland’s inalienable right of self-determination.”

And Americans did: Even President Wilson, who, despite his skirmishes with the American Irish, began to call for the liberation of small nations from colonial powers.

Americans were there, too, to greet Éamon de Valera when he arrived in New York in June 1919 to secure American recognition for an Irish Republic and to raise funds from the Irish-American community. De Valera spent the following 18 months in the U.S. giving speeches to as many as 60,000 people in some of America’s largest venues, including Madison Square Garden and Fenway Park.

Ireland was a fledgling nation, and de Valera might have been needed at home to lead, but America, which had supported the cause of Irish freedom through thick and thin, simply could not be ignored. ♦

_______________

Tom Deignan writes columns about movies and history for Irish America, and is a weekly columnist for The Irish Voice and regular columnist and book reviewer for the Newark Star-Ledger.

Leave a Reply