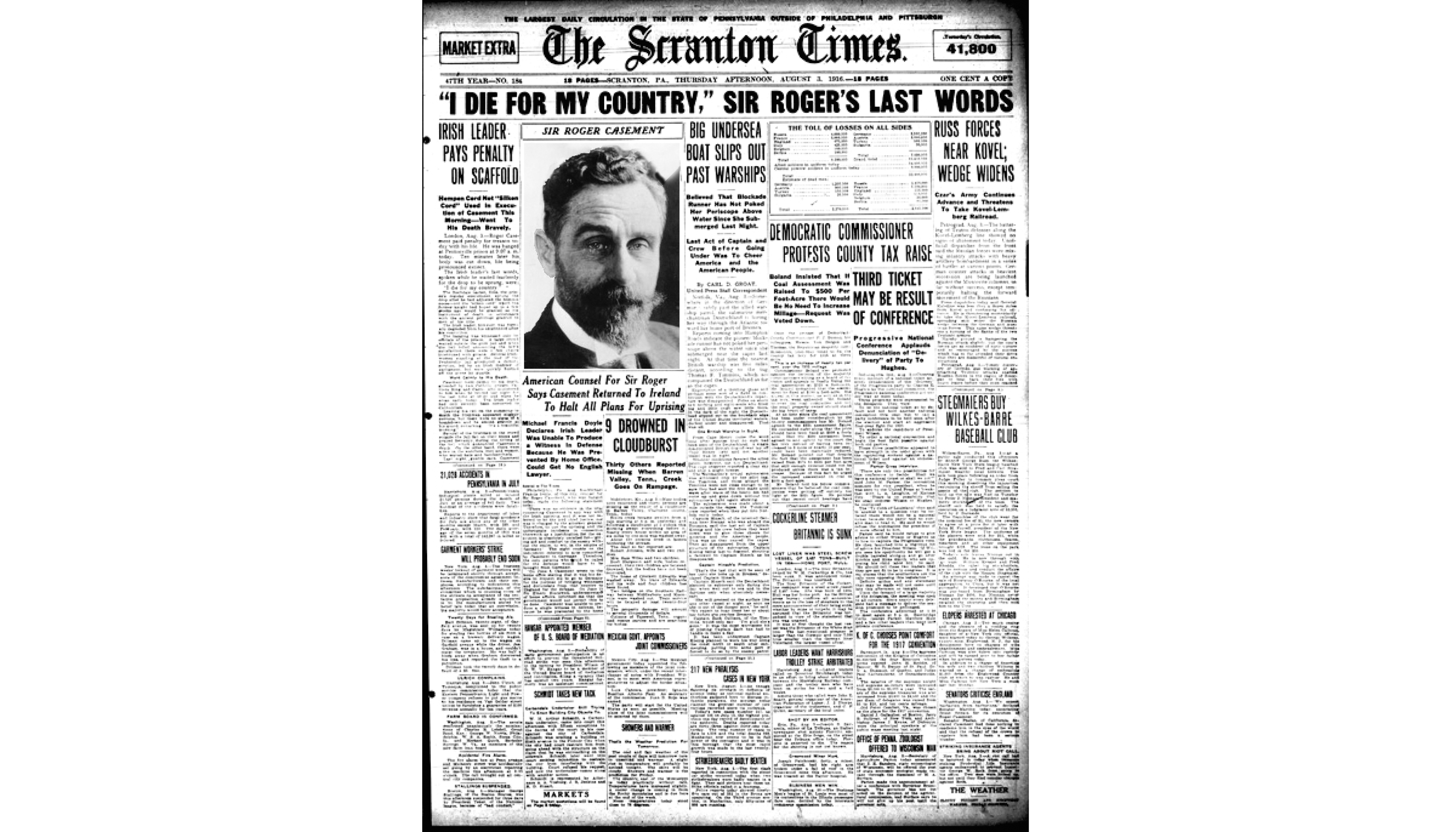

Hanged by the British in 1916 for working with Germany and Irish nationalists in planning the Easter Rising of 1916, Sir Roger Casement is remembered as the “father of twentieth-century human rights investigations.”

Standing in the gallows of Britain’s Pentonville Prison, Casement was asked by the governor if he had any final words. He did, but only one: “Ireland.” The hangman, moved by his elegant bearing, gently adjusted his tie after placing the noose around his neck. When it was all over, his body was thrown naked in an open grave, covered with quicklime and laid beside the notorious wife murderer, Dr. Crippen. The quicklime, the execution by hanging (not firing squad), and his graveyard companion were Britain’s way of showing their contempt for him – the traitor, the fallen knight, and the homosexual.

Roger Casement was born in Dublin in 1864. His father, an army captain, was a Protestant and his Cork-born mother was a Catholic who had her children secretly baptized. Like his country, Casement was a study in contradictions – he has been called “a microcosm of Ireland:” Dubliner, Ulsterman, Catholic, Protestant, poet, and patriot.

Orphaned at a young age, he lived with his father’s family in Antrim. He was a child of promising intellect who wrote poetry and immersed himself in Celtic myths. Unwilling to accept the charity of relatives, Casement left school at 15 to work for a shipping company in Liverpool. He had always dreamed of far-off places and now the handsome, hardworking clerk was soon promoted to be the British Consul, serving in West Africa.

Word of the brilliant Casement had reached the British Foreign Office. So, too, had word of the atrocities in King Leopold II’s private fiefdom, the Belgian Congo. Leopold, a staunch imperialist was perpetuating genocide there, eventually killing 10 million natives. He became, thanks to Congo resources, the richest man in Europe. The Foreign Office sent Casement into the Congo to investigate, photograph, and bear witness. He took the testimony of Africans who told stories of endless barbarity, murder, and mutilation.

It was a job that forever ruined his health. It forever changed his life too. Exploitation and greed, he realized, were business as usual for empires, including the world’s largest, the British Empire. His dormant Irish nationalism awoke; he shed his Anglo skin and found the Irishman underneath. He wrote his sister, “This journey into the depths of the Congo has been useful in helping me discover my own country and understand her destiny. In these jungles, I’ve found not only the true face of Leopold II. I’ve also found my true self: the incorrigible Irishman.”

Released in 1904, The Casement Report, a litany of horrors, forced Leopold to quit the Congo.

Having sparked the world’s first human rights campaign, Casement was awarded one of Great Britain’s highest citations, the Order of St. Michael and St. George. But that same year Roger Casement joined the Gaelic League and signed, for the first time, his name as Ruairí Mac Easmainn. The British Empire had forever lost her international hero.

In 1906, the “incorrigible Irishman” was again drawn into the belly of the beast – the Putumayo basin in Peru. The Peruvian Amazon Company, was the world’s largest exporter of rubber. It was run by the fiendish Julio Arana, but was registered in London, thereby making it a British company. Dispatched into the Amazon rain forest, Casement discovered that the P.A.C. had systematically enslaved, tortured, and murdered Indians to reach rubber quotas.

His findings were made public and an embarrassed Great Britain forced P.A.C.’s Board of Directors to resign. Subsequently, it laid claim to the famous humanitarian, and Roger Casement was to be a Knight of the Realm. Casement was anguished: the title would elevate his diplomatic efforts on behalf of Irish nationalism but, still, how could he accept such an “honor” from a regime that had enslaved his country for centuries? He told his sister that rather than being knighted, he “ought really to be in jail.” Prophetic words: five years later he was in the Tower of London awaiting execution.

In 1913, Sir Roger became an official Irish rebel when he joined the Irish Volunteers and visited New York to raise money for the Rising. He worked with John Devoy of Clan na Gael who, at first put off by his title, soon accepted him into the brotherhood, always addressing him, not as Sir Roger, but simply, “Rory.”

During World War I, operating on the principle, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” Casement and Devoy met with a German diplomat. They promised Ireland would remain neutral if Germany helped the coming Easter Rising by supplying guns and expertise. In Germany, Casement tried to secure arms and persuade Irish P.O.W.s to form an Irish Brigade. After two years, both initiatives were disappointments. There was no brigade – Irish soldiers wouldn’t dishonor their oath to the King – and Germany could only deliver some 20,000 guns, a fraction of the weaponry needed. Worse, British Intelligence was intercepting his messages.

The Easter Rising was imminent. Believing that there were not sufficient arms for the rebellion, Casement slipped out of Germany by submarine to warn the leaders. He placed the armaments on a separate boat, the Aud, flying under a Norwegian flag, which he planned to meet on the Irish shoreline.

First to arrive was the Aud, but it was ambushed by the waiting British navy and taken to Cork.

Unaware of the plight of the gun-runner, Casement had moved from the submarine to a dinghy. But this capsized, leaving him to swim onto Banna Strand in County Kerry.

It was 3:00 a.m., Good Friday, 1916. Once on land, Casement, ill, drenched, and exhausted, found there was no one to meet him. Still, he rejoiced:

“I was for one brief spell happy and smiling once more… all round were primroses and wild violets and the singing of the skylarks in the air and I was back in Ireland again.”

His happiness was short-lived. He soon heard a voice – “Sir Roger?” When the Easter rising began and the Proclamation of the Irish Republic was read, Casement was in the Tower of London.

His trial at the Old Bailey lasted four days. It took the jury one hour to find him guilty, strip him of his knighthood, and condemn him to death by hanging. After his sentencing he delivered a speech from the dock, arguably one of the greatest political statements of all time. He stated, logically – and ironically, since he had a cultured British accent – that he couldn’t commit treason against England since he wasn’t an Englishman to begin with. Then he railed against the colonial system, “…where men must beg with bated breath for leave to subsist in their own land, to think their own thoughts, to sing their own songs…surely it is a braver, a saner, and a truer thing to be a rebel…”

Because he was a renowned human rights activist, pleas to have his death sentence commuted came from around the world. But Britain, determined to see the execution proceed, produced a secret weapon. They circulated the Black Diaries purportedly written by Casement and relating his homosexual activities in the Congo and South America. The infamous diaries remain controversial today as many consider them forgeries written by the British Secret Service. Others acknowledge they were written in Casement’s hand but were only the fantasies of a lonely, exhausted, and sick man. No matter, since the diaries proved to be, as much as his rebellion, the reason he was hanged. Now he died on the gallows as both a traitor and a pervert.

After receiving the last rites of the Catholic Church, Roger Casement was executed on August 3, 1916, the sixteenth and final leader of the Rising to be executed. His final wish, “Bury me in Ireland,” and his family’s plea for his body were denied. This gratuitous cruelty inspired W.B. Yeats to write, “The Ghost of Roger Casement” – in which the poet sees Casement’s spirit coming across the sea, knocking on the door, still wanting to come home:

O what has made that sudden noise?

What on the threshold stands?

It never crossed the sea because

John Bull and the sea are friends;

But this is not the old sea

Nor this the old seashore.

What gave that roar of mockery,

That roar in the sea’s roar?

The ghost of Roger Casement

Is beating on the door.

Casement was late to enter the pantheon of 1916 martyrs, marginalized, no doubt, by his sexuality. Finally, in 1965, an Irish military escort removed his remains from the prison graveyard in London and accompanied them to Ireland for a state funeral. Hundreds of thousands came to pay him tribute including the very conservative President de Valera, a veteran of the Easter Rising, who delivered his eulogy.

He lies today in the Heroes section of Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery where his name, Ruairí Mac Easmainn is carved on a gravestone reading, in Gaelic, “He died for Ireland.”

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best- selling humor/reference book, Saints Preserve Us! (Random House) currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info/entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She’s currently co-writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

This article was originally published in the February / March 2016 issue of Irish America. ♦

The alleged “genocide” by Belgian King Leopold II of 10+ million Congolese people in 23 years does not make sense. Joseph Ki-Zerbo, the most respected African historian, calculated that in 1903, supposedly one of the peak years of the rubber production, the total figure of Congolese workers in this industry was only 43,500. It is impossible to reconcile these findings with the totally inflated 10-million figure which would have required the death of 435,000 Congolese per year or about 1,200 per day, with a population of maximum 1,500 Europeans in 1906.

“It is quite natural to prefer lies to truths, they are less complicated.” (translated from Franz-Olivier Giesbert, Dictionnaire d’anti-citations pour vivre très con et très heureux, Paris 2013).

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leopold-II-king-of-Belgium

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leopold-II-king-of-Belgium