Within sight of the Irish Embassy is Kerry-born sculptor Jerome Connor’s famous memorial to Irish patriot Robert Emmet, commissioned in 1916 by a group of Irish Americans (including the singer John McCormack) to commemorate Irish independence. Connor chose to render Emmet delivering his famous speech from the dock, an enduring symbol of the struggle for freedom, because without Emmet, there would quite simply have been no 1916 Rising.

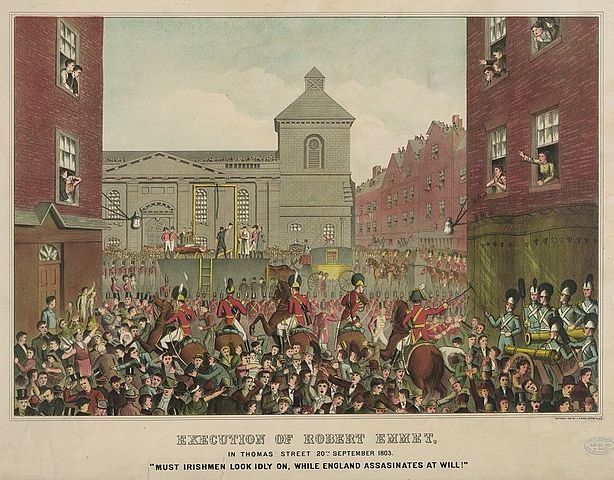

Robert Emmet was born in 1778 to a family of Irish patriots imbued with passion for Irish independence. In 1803, Emmet led an armed insurrection that proclaimed an Irish Republic. The rebellion was crushed by British troops; Emmet was captured, tried, and sentenced to death.

In his inspiring speech Emmet proclaimed: “I wished to procure for my country the guarantee which Washington procured for America.” His concluding words have echoed through the ages: “When my country takes her place among nations, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written.”

In 1803, the 25-year-old Emmet was executed by hanging and beheading. His legacy helped inspire the sequence of events resulting in Irish independence: the 1916 Easter Rising, which set off the War of Independence, the Irish Civil War, and the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

In 1917, the Robert Emmet Statue Committee, with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson in attendance, presented its gift to the Smithsonian and the American people. The sculpture was placed on view in the rotunda of the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Museum (now the National Museum of Natural History). To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Rising, the sculpture was moved to its present site on April 22, 1966, on long-term loan to the National Park Service.

The seven-foot-tall sculpture of Emmet proved so popular that in 1918, the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Emmetsburg, Iowa, commissioned a copy of the statue that now stands in the city’s courthouse square. A copy was also cast and unveiled in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in 1919 by Irish leader Eamon de Valera. In 1922, Congress authorized the gift of a third replica to the National Gallery of Ireland that now stands in St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin.

The statue will be re-dedicated in March 2016 to commemorate the centennial of the Easter Rising. The Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Irish American Unity Conference are spearheading the collaboration with the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Park Service.

Jack O’Brien, who was instrumental in creating a memorial to Commodore John Barry as well as the Irish Brigade Monument at Antietam National Battlefield, sees the Emmet statue as a priority for the Irish community in Washington. “We have a synergy of centennials here, one to honor the heroes of the Rising and the other to honor the great work Connor created in 1916,” he says.

Jerome Connor (pictured right) was born in Coumduff, Annascaul, on the Dingle Peninsula, in 1874. In 1888 he immigrated to Massachusetts, where he trained as a stonecutter and bronze founder before moving to the Stickley arts and crafts center in Syracuse.

As a young man, he became interested in Walt Whitman and made studies for a monument to Whitman and a commemorative Whitman medal (1905) that brought him critical notice as a sculptor. In 1910 he settled in Washington, D.C.

When the Irish Free State was established, Connor returned to Ireland and executed designs for the new coinage and relief portraits of leading politicians. “His work celebrated heroes of America’s past and subjects that resonated with the Irish-American community,” wrote historian John Turpin. “His work in Ireland related to the struggle for independence. Connor’s best work was modeled from life, as in the two fishermen on the Lusitania Memorial.”

The Lusitania Memorial was a prestigious project that ended tragically for Connor. In 1925, he was commissioned to create the memorial in Cobh, Co. Cork, to commemorate the 1,198 lives lost in the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915.

But by 1943, the year of Connor’s death, the Lusitania Memorial was not complete, and he died penniless. Sculptor Domhnall O’Murchadha saved the principal plaster figures in Connor’s studio and supervised the memorial’s completion.

O’Murchadha helped to form the Jerome Connor Trust, which enabled the National Gallery of Ireland to offer its collection of small bronzes to Connor’s home town of Annascaul. A permanent sculpture gallery for the collection officially opened in 2014 at the South Pole Inn in Annascaul. Tom Kennedy, who consults with art historian Catherine Marshall, encourages visitors. “We welcome all to our gallery. Your visit will honor this remarkable Irishman, Dingle’s native son, who does us all proud in America and in Ireland.” ♦

Learn about Robert Emmet’s brother Thomas Addis Emmet and his legacy, read The United Irishmen and their American Legacy and Irish Patriot Remembered from Irish America.

A very nice tribute to Robert Emmet and Jerome Connor. Consequent to further discussions with the National Park Service and Smithsonian, the re-dedication will be held on April 27, 2016.

Peter Kissel, Irish American Unity Conference.

I enjoyed reading this article about my ancestor and thank you! I am somewhat of a rebel too = but not Republican. I am Independent and think and research every issue and candidate before deciding my support. I am a political reporter and editor, no surprise! Again, I thank you.

She is far from the land, where her young hero sleeps,

And lovers are round her, sighing;

But coldly she turns from their gaze, and weeps,

For her heart in his grave is lying!

She sings the wild song of her dear native plains,

Every note which he lov’d awaking

Ah! little they think, who delight in her strains,

How the heart of the Minstrel is breaking!