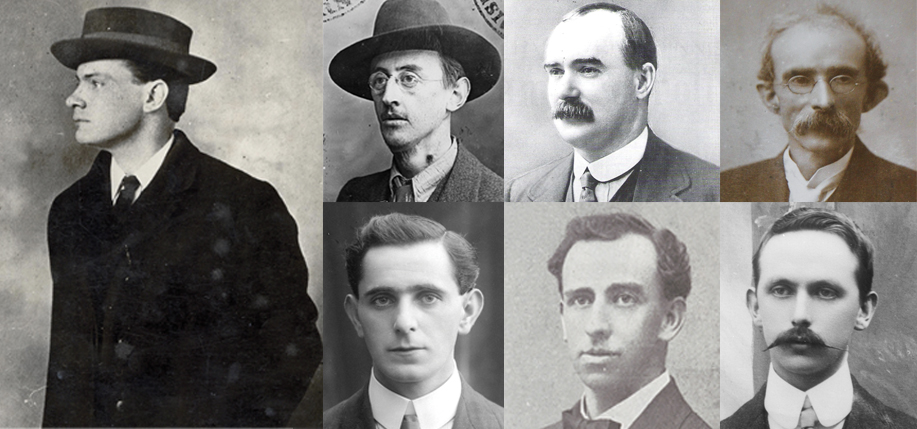

The 16 men who were executed in the aftermath of the Easter Rising included the seven leaders who sealed their fate by signing the Proclamation (Forógra na Poblachta). It was read by Pádraig Pearse outside Dublin’s General Post Office, on April 24, 1916. The names of the seven as they appear on the Proclamation are: Thomas J. Clarke (who was invited to be the first signatory because of his involvement with the Fenian movement since the 1870s); Seán MacDiarmada, Clarke’s right-hand man; Thomas MacDonagh, commandant of the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers; P. H. Pearse, president of the provisional government and commander-in-chief of the army of the Irish Republic; Éamonn Ceannt, commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Irish Volunteers; James Connolly, commandant-general of the forces of the Irish Republic in Dublin; and Joseph Plunkett, an original member of the I.R.B. Military Committee responsible for planning the Rising.

The leaders and seven other rebels were executed by firing squad in the Stonebreakers’ Yard at Kilmainham Gaol. Two others were also executed for the part they played in the Rising: Thomas Kent faced a firing squad at Cork Detention Barracks, and Roger Casement, whose hanging at Pentonville Prison in London, on August 3, 1916, brought to an end the executions of those involved. The men were from various backgrounds, and the extent of their involvement in the Rising varied greatly. Here are their histories.

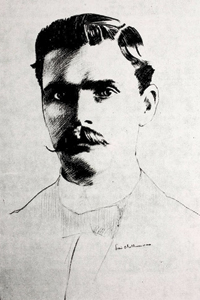

Éamonn Ceannt

September 21, 1881 – May 8, 1916

Éamonn Ceannt was born Edward Thomas Kent in Ballymoe, Glenamaddy, Co. Galway to parents James and Johanna (née Galway) Kent. James Kent was a fluent speaker of Irish, and after the 1898 centenary commemorations of the United Irishmen’s insurrection, Ceannt took a keen interest in cultural nationalism and began to learn Irish under the tutelage of his father. Before long, he adopted the better-known Gaelicized version of his name.

Éamonn Ceannt was born Edward Thomas Kent in Ballymoe, Glenamaddy, Co. Galway to parents James and Johanna (née Galway) Kent. James Kent was a fluent speaker of Irish, and after the 1898 centenary commemorations of the United Irishmen’s insurrection, Ceannt took a keen interest in cultural nationalism and began to learn Irish under the tutelage of his father. Before long, he adopted the better-known Gaelicized version of his name.

Ceannt joined the Gaelic League in 1899. It was in the League that he met Pádraig Pearse, as well as Irish language scholar and future Sinn Féin politician Eoin MacNeill. His interest in Gaelic culture did not end with the Irish language. He became a serious musician, mastering the uilleann pipes and traveling throughout Ireland collecting folk songs. Ceannt was known as a particularly devout and abstemious Catholic and also traveled to Rome to play the uilleann pipes for Pope Pius X at his jubilee celebration.

Ceannt was an early member of Sinn Féin and was eventually elected to its national council. Ceannt also had a penchant for socialism, was an avid reader of Marx and Engels, and was active in the campaign to unionize his fellow workers at the Dublin Corporation. When the aristocratic-leaning leader of Sinn Féin, Arthur Griffith, berated the workers who participated in the famous 1913 lockout, Ceannt objected on their behalf.

Seen by his colleagues as an uncompromising and militant nationalist, Ceannt was brought into the Irish Republican Brotherhood by Seán Mac- Diarmada. He also played a significant role in the importation of arms for the Irish Volunteers and was present at both the Howth and Kilcoole gunrunnings. Following the split in the Volunteers between Redmond’s National Volunteers and the Irish Volunteers, Ceannt became the commander of the 4th battalion, Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers, and eventually joined the I.R.B. Military Council.

During Easter week, Ceannt’s battalion fought at the South Dublin Union, a workhouse and hospital near several army barracks. This position also controlled one of the main roads to the city and consequently, Ceannt and his small group of men were involved in some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising. Ceannt was a fearless leader and earned the admiration of his men when he led them into battle from the front. He is also said to have been deeply disappointed when the news of the surrender by the leadership in the G.P.O. reached his position. Along with Pearse, Ceannt had a proclivity for romantic imagery and the rhetoric of blood sacrifice. He likely had hoped for a fight to the death with the British, rather than an inglorious surrender.

In his final moments, Ceannt, the ever staunch Catholic, remained humble and turned to his faith for comfort when he knew his life was about to end. “I wish to record the magnificent gallantry and fearless, calm determination of the men who fought with me,” he wrote from Kilmainham Gaol on May 7, one day before his execution. “All, all, were simply splendid. Even I knew no fear nor panic and shrunk from no risk even as I shrink not now from the death which faces me at daybreak. I hope to see God’s face even for a moment in the morning. His will be done.”

But Ceannt was not all calm and fearlessness. He admitted to his wife on the day of his execution, “My cold exterior was but a mask. It has saved me in these last days.” Then he wrote a rare but sweeter message to his soon-to-be-widow. He reminded her to be strong and to never forget, “You will be – you are, the wife of one of the Leaders of the Revolution.” – R. Bryan Willits

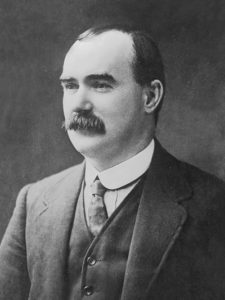

James Connolly

June 5, 1868 – May 12, 1916

In 1868, James Connolly was born in Edinburgh to John Connolly and Mary McGinn, both Irish Catholic emigrants. He was the youngest of three boys. His family lived in extreme poverty, and he had to leave school at the age of 11 to work. At 14, he joined the British Army and served in Ireland for seven years. He deserted in 1889 when his parents were seriously ill. In the same year, he married Lillie Reynolds, from a protestant Wicklow family. The couple had one son and six daughters.

Connolly spent his adolescence voraciously reading books on history, economics, politics, and socialism. In 1890, when he and his family returned to Edinburgh, he became active in socialist organizations. He lost his job in 1894, but his reputation among socialist circles in Scotland earned him an employment offer from the Dublin Socialist Club in 1896. When he moved to Dublin, he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party and formed a friendship with Maud Gonne, whose influence inspired him to support women’s suffrage. The two organized many anti-monarchist protests. He also began a newspaper, The Workers’ Republic, which had sporadic success.

Unlike the other future members of the Provisional Government, Connolly opposed Home Rule, which he dismissed as middle class and capitalist. In 1900, he wrote, frustrated, that “Ireland without her people is nothing to me.”

In 1903, discouraged by Irish socialists, Connolly and his family emigrated to America. He became active in American leftist and Irish nationalist circles and became the New York organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (the “Wobblies”). Connolly founded the Irish Socialist Federation in 1907 and its newspaper, The Harp, the following year. In the United States, Connolly wrote his most famous works, including, “Labour in Irish History,” which applied international thinking to the Irish situation and greatly influenced Pádraig Pearse, and “Labour, Nationality, and Religion,” which asserted that Catholicism and socialism were not incompatible. Both pieces were later published in Dublin, in 1910, when Connolly returned to Ireland, following several disagreements with American socialists.

After his return from America, Connolly worked as the Belfast organizer for the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, which was founded by Jim Larkin. In 1912, he helped found the Independent Labour Party of Ireland, from which the modern Irish Labour Party evolved. Connolly was famously instrumental during the 1913 Dublin Lockout, when the Dublin Employers’ Federation locked their employees out of work to prevent them joining trade unions. The Irish Citizen Army was formed to protect locked out workers, and when the lockout ended in early 1914, Connolly became its commandant.

When World War I began, Connolly helped organize massive anti-recruitment protests. When those protests failed, he aligned himself with the Irish revolutionary cause, and joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in early 1916.

Connolly’s writing had made a deep impression on Pádriag Pearse, who penned the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, and Connolly’s influence is apparent in the proclamation’s egalitarian, socialist, and feminist elements. At the establishment of the Provisional Government, Connolly was named vice president.

During Easter Week, 1916, Connolly directed military operations at the General Post Office as commandant-general of the Dublin division of the Irish Republican Army. He suffered a serious ankle wound, but continued to command the garrison. After the surrender, he was tried by court-martial and sentenced to death. Connolly was so gravely wounded that it was estimated he would not have lived more than a few days, but was executed on May 12th, regardless. Unable to stand, he had to be tied to a chair to face the firing squad, cementing his legacy as a martyr for the Republican cause. – Julia Brodsky

Joseph Mary Plunkett

November 21, 1887 – May 3, 1916

Joseph Mary Plunkett was born in Dublin to George Noble Plunkett and Josephine Plunkett (née Cranny), the second son of a prominent and wealthy Catholic family. Not only was his father a papal count, but he boasted among his relatives the martyred bishop Oliver Plunkett; Sir Horace Plunkett, a leading figure of the cooperative movement in Ireland; and the writer Edward Plunkett, who was the 18th Lord of Dunsany. Joseph Plunkett came from the most well-to-do background of those who led the Rising.

Joseph Mary Plunkett was born in Dublin to George Noble Plunkett and Josephine Plunkett (née Cranny), the second son of a prominent and wealthy Catholic family. Not only was his father a papal count, but he boasted among his relatives the martyred bishop Oliver Plunkett; Sir Horace Plunkett, a leading figure of the cooperative movement in Ireland; and the writer Edward Plunkett, who was the 18th Lord of Dunsany. Joseph Plunkett came from the most well-to-do background of those who led the Rising.

Plunkett was a sickly child who developed glandular tuberculosis at a young age. His many ailments, and his turbulent, ambulatory upbringing left him with an eccentric and introspective personality. He eventually became an erudite scholar and studied in Paris, England, and Ireland. He was a polymath and pursued a myriad of interests, ranging from the hard sciences to mysticism and poetry. It was this latter interest that brought him into contact with Thomas MacDonagh, whom he originally sought out as an Irish language tutor.

Despite the disparate personalities of these two men and their contesting views of religion, their relationship flourished to such an extent that Plunkett became engaged to MacDonagh’s sister-in-law, Grace Gifford.

“Of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic,” Gifford wrote from the jail on their wedding day, “Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh were the most like each other, and from this fact resulted in the inseparable friendship which existed between them. Both were warm, kindly, and essentially human – but to Joseph Plunkett the love of his friends – the beauty of nature – the arts and sciences stood for one thing only – the expression of God’s divine power.”

MacDonagh encouraged Plunkett to write poetic verse, and he eventually published a book of poetry, The Circle and the Sword, with MacDonagh’s help. Plunkett also became the owner and editor of Irish Review, a journal that published articles on science, economics, politics, history, and the Irish language. In its day, it was considered to be one of the best journals of its kind.

Just before Plunkett acquired Irish Review, it had publish an article by a British consular with whom Plunkett would thereafter be inexorably intertwined. The article was titled, “Ireland, Germany and the Next War” and was published under the nom de plum “Shan Van Vocht.” Its author was Sir Roger Casement.

Plunkett and Casement went on to become friends and founders of the Irish Volunteers. After Casement traveled first to Germany by way of America in 1914, Plunkett also arrived in Berlin, and alongside Casement, negotiated with the German Imperial Government for arms and munitions for a revolution in Ireland. Plunkett also played a role there in trying to establish the ill-fated Irish Brigade made up of Irish P.O.W.’s held in prison camps in Germany.

Plunkett later traveled to America to meet with John Devoy and the Clan na Gael revolutionary directory. He had to be brought in under dubious pretenses due to immigration restrictions on those infected with tuberculosis. After briefing the Clan, Plunkett also convinced the socialist and labor leader, James Connolly, to join ranks with the I.R.B. Pádraig Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt, Connolly, and Plunkett are presumed to have devised the majority of the final plans for the Easter Rising.

A part of the Plunkett family estate outside Dublin was used to store weapons, train soldiers, and manufacture explosives in preparation for the Rising. Just weeks before Easter, Plunkett’s lifelong ailments continued to dog him, and despite having recently undergone surgery, was present when the Rising began and fought in the G.P.O. alongside the other members of the Provisional Government.

He and Gifford were married in Kilmainham Gaol just hours before his execution on May 3. – R. Bryan Willits

Pádraig Pearse

November 10, 1879 – May 3, 1916

Pádraig Pearse was born in Dublin to James Pearse, who originally hailed from London, and his second wife, Margaret Brady. Pearse became exceptionally enamored with the Irish language at a young age and joined the Gaelic League in 1896. He was founding literary societies and delivered papers and lectures on the Irish language and culture in his teenage years.

Pádraig Pearse was born in Dublin to James Pearse, who originally hailed from London, and his second wife, Margaret Brady. Pearse became exceptionally enamored with the Irish language at a young age and joined the Gaelic League in 1896. He was founding literary societies and delivered papers and lectures on the Irish language and culture in his teenage years.

In 1908, he established a bilingual boys’ school, Saint Enda’s, and a lesser-known school for girls called St. Ita’s. These places proved to be a breeding ground for the revolution, as three of his instructors, Thomas MacDonagh, Con Colbert, and Pearse’s brother Willie would all go on to fight in the Easter Rising and were all executed along with Pearse. Many of the older boys from St. Enda’s fought at the G.P.O. as well, and as the final letters from Pearse show, their fate remained in his thoughts until moments before his execution.

Pearse was not always a radicalized nationalist with revolutionary aims. He started his career as a cultural nationalist and was a long-time supporter of the Home Rule Bill. But once it became clear that cultural and constitutional nationalism would not free Ireland from its British colonial overlords, he advocated the use of physical force. Recent scholarship also suggests that, after Pearse helped set up the Irish Volunteers and was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood, it was during his travels in America where he met John Devoy and other influential leaders of Clan na Gael that his transformation into a radical republican was completed.

Pearse was regarded as a powerful orator, and it was the graveside panegyric he delivered over the repatriated remains of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa that brought him particular renown. This speech, delivered on August 1, 1915, is especially remembered for its final line: “but the fools, the fools, the fools! – they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.” This remark was later seen by many as a call to arms, coming as it did just several months before the Easter Rising.

Along with MacDonagh and James Connolly, Pearse is also assumed to have written the majority of the text in the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, which, as president of the Provisional Government, he read aloud from the portico of the General Post Office on Easter Monday, just before the fighting commenced.

After nearly a week of fighting, Pearse sent nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell to General Lowe to declare his intentions to surrender. Lowe was unconvinced either because O’Farrell first carried only a verbal message or, as some have suggested, because he refused to negotiate with a woman.

Ultimately Pearse returned with a message for surrender that read in part, “In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at Headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender.”

At his May 2 court-martial, Pearse exaggerated his role in the fighting in order to spare the lives of his comrades. He was executed by firing squad in the early morning hours of May 3, 1916. Before dying, he wrote to his mother, saying “This is the death I should have asked for if God allowed me my choice of all deaths.” – R. Bryan Willits

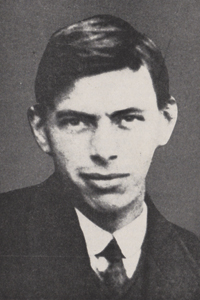

Seán MacDiarmada

January 27, 1883 – May 12, 1916

Seán MacDiarmada was born John Joseph McDermott in 1883 near Kiltyclogher, Co. Leitrim, to Donald McDermott and Mary McMorrow. He received his education in the national school at Corradoona and later attended night school in Tullinamoyle, Co. Cavan, where he learned bookkeeping and Irish.

After spending time in Scotland, he settled in Belfast in 1905 and began working as a tram conductor and barman. Belfast was also where MacDiarmada began his interest in politics and joined the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Gaelic League. He was also sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood by Dennis McCullough, whom he helped to organize the Dungannon clubs, which were precursors to Sinn Féin.

MacDiarmada moved to Dublin in 1907 and there met Tom Clarke, whose friendship and guidance would shape his political life and ultimately determine his fate. Under Clarke’s influence, he became a full-time organizer for the I.R.B. and managed Irish Freedom, the Brotherhood’s newspaper. In 1911, MacDiarmada, together with McCullough and Clarke, formed a three-man executive, that gave them control of the I.R.B. MacDiarmada and McCullough also created the group’s military council, which would later plan the 1916 Easter Rising.

In 1911, MacDiarmada was struck with what was then identified as polio (but may have been tuberculosis), which forced him to walk with a stick thereafter. It is said, however, that his disability only sharpened his resolve to fight for Ireland’s independence. He maintained his activity as an organizer for the I.R.B., often infiltrating other republican organizations and recruiting their members. In August of 1914, he campaigned against Irish soldiers joining the British army, an activity for which he earned four months in prison.

In a speech that same year in Tralee, Co. Kerry, MacDiarmada said, “The Irish patriotic spirit will die forever unless a blood sacrifice is made in the next few years.” This pronouncement was not simply fiery rhetoric to excite the crowd. Upon his release from prison, he joined the I.R.B. military council and with them began planning the Rising.

In organizing the Easter Rising, MacDiarmada kept in mind that previous Irish rebellions had been undermined by spies and informants and became notoriously secretive in his plans, so much so that the lack of communication with his comrades may have contributed to much of the disorganization and confusion once the Rising began.

During the events of Easter Week, when he held the General Post Office with the other members of the Provisional Republican Government, MacDiarmada was unable to engage directly in the fighting due to his limp and did not hold an official military rank, but he was acknowledged as one of the garrison leaders. Executed May 12, he and James Connolly were the last two of the Rising’s leaders to have their death sentences carried out. MacDiarmada had no illusions about his fate, and wrote that “the executions will create a reaction in this country that will wipe out the slavish pro-English spirit.”

Despite his limp, he was described as being handsome, with dark hair and blue eyes. He is reported to have been courting Mary Josephine Ryan (nicknamed “Min”), of County Wexford, and acknowledged in one of the final letters that had he lived, Min would have likely become his wife. Ryan herself was of a political bent; she was one of the founding members of Cumann na mBan and had been a courier to the G.P.O. during Easter Week. Following MacDiarmada’s execution, she managed to escape arrest and emigrated to the United States.

Though he is not typically thought of as the most famous of the Rising’s organizers, Irish cleric, and historian, F.X. Martin, named Seán MacDiarmada the “mainspring” of the Rising in a series of radio lectures in the 1960s. The Rising, the upcoming 2016 film, will focus on MacDiarmada as the mastermind of the rebellion.– Julia Brodsky

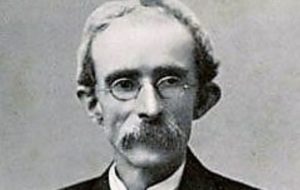

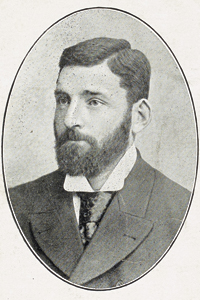

Thomas J. Clarke

March 11, 1858 – May 3, 1916

Tom Clarke was the first signatory of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, a lifelong advocate of armed rebellion, and one of the Rising’s primary links to U.S. support.

Tom Clarke was the first signatory of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, a lifelong advocate of armed rebellion, and one of the Rising’s primary links to U.S. support.

Born on the Isle of Wight to James Clarke, an Irish sergeant in the British Army, Clarke was raised in England and later South Africa. The family eventually settled in Dungannon, Co. Tyrone, in 1865, where James was stationed. Though James was a member of the Church of England, Tom was raised Catholic, the faith of his mother Mary Palmer. He attended Saint Patrick’s national school. By his mid-teens, he was a member of the Fenians and by his late teens, had joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood, serving as the head of the local Dungannon chapter. He was involved in a number of clashes with the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Orange Order and fled to the United States in 1882 to avoid arrest, and in the U.S. joined Clan na Gael.

The following April, Clarke was sent to London on a Fenian bombing mission to destroy London Bridge. He was betrayed and arrested while in possession of explosives at the age of 25. He was sentenced to penal servitude for life and served 15 years. His years in various prisons – Millbank, Chatham, and Portland – were extremely harsh and are recounted in his posthumous memoir Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life (1922). On his release, he returned to America. He resumed work with Clan na Gael, and served as an assistant editor to Clan na Gael leader John Devoy’s newspaper, the Gaelic American. In prison, he met fellow Fenian John Daly, uncle of Ned Daly, who was also executed for his role in the Rising, and Kathleen Daly, whom he married despite being 21 years her senior.

Clarke became an American citizen in 1905, and he and his wife lived in Brooklyn and Long Island until 1907, when they, along with their three children, returned to Ireland and settled in Dublin. There, Clarke established a tobacconist business on Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street) and Amiens Street but was still primarily concerned with making Ireland a free republic. He became highly active in the I.R.B., which was undergoing a leadership change in favor of more youthful leaders. He acted as a mentor to the likes of Bulmer Hobson, Denis McCullough, and Sean MacDiarmada, with whom he would plan the Rising and who would also sign the Proclamation.

When the Irish Volunteers formed in 1913, Clarke saw them as the natural army of revolution and joined as a member. He refused to take a formal leadership role due to his status as a known Fenian felon. Throughout this time, he was a crucial link to the U.S. Irish republican base, and was eventually appointed to the I.R.B.’s Military Council in 1915. This council was directly responsible for coordinating the Rising. Clarke is said to have outlined the general strategy while MacDiarmada was responsible for tactical planning. Officially, however, Clarke never held a military role or rank with the Irish Volunteers or the I.R.B.

During the Rising, he was stationed at the G.P.O. with the majority of the other signatories and though he refused military rank, participated in the fighting throughout the week. Following the surrender, he was held at Kilmainham and was the second to be executed, after Pádraig Pearse. “I and my fellow signatories believe we have struck the first successful blow for Irish freedom,” he wrote to his wife from prison. “The next blow, which we have no doubt Ireland will strike, will win through. In this belief, we die happy.”– Adam Farley

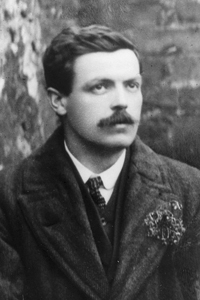

Thomas MacDonagh

February 1, 1878 – May 3, 1916

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan, Co. Tipperary, to schoolteachers Joseph MacDonagh and Mary Parker. Their home was a literary one, and Thomas developed an interest in storytelling and writing at a young age. He attended Rockwell College, near Cashel, Co. Tipperary, when he was 14 years old, with the intention of entering the priesthood.

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan, Co. Tipperary, to schoolteachers Joseph MacDonagh and Mary Parker. Their home was a literary one, and Thomas developed an interest in storytelling and writing at a young age. He attended Rockwell College, near Cashel, Co. Tipperary, when he was 14 years old, with the intention of entering the priesthood.

In 1901, he left Rockwell and taught for some years in Kilkenny and Cork. During this time, he joined the Gaelic League and ignited his interest in Irish nationalism. He later traveled to the Aran Islands to improve his Irish fluency, and there met Pádraig Pearse, who invited MacDonagh to join the teaching staff of his own St. Enda’s school. While teaching, MacDonagh earned his Bachelor’s and Master of Arts degrees at University College, Dublin, where he was later appointed as a lecturer in 1911.

During the 1900s, MacDonagh wrote several plays, poems, and critical essays, many of which had a nationalist theme. He circulated among Dublin’s literary and artistic sets and became friends with Padraic Colum, George Russell (Æ), Arthur Griffith, and Joseph Plunkett. He and Colum, along with James Stephens and David Houston, founded the monthly Irish Review. He wrote a play entitled When Dawn is Come, which depicted Ireland rising against English rule. It was performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1908 and called the “first Sinn Féin drama.” MacDonagh published his most accomplished work, Lyrical Poems, in 1913, a selection of original work and translations from the Irish.

In 1914, he, Plunkett, and Joseph Martyn established the Irish Theatre on Hardwicke Street. They believed Dublin needed a home for theater that focused on the realism of Irish life in contrast to the fantasy and romance of the Abbey.

MacDonagh carried on a relationship with Mary Maguire (who would later marry Colum and establish herself as a poet in her own right) until 1910, and in 1912, married Muriel Gifford, a protestant, despite her family’s disapproval. The couple had a son, Donagh, and a daughter, Barbara.

In addition to his literary and theatrical activities, MacDonagh was consistently involved in nationalist politics. During the 1913 lockout and labor dispute, he was a member of the Dublin Industrial Peace Committee, and he later joined the Irish Volunteers when they formed that same year. He became a member of their leadership and took part in their Howth gunrunning operation in 1914. Despite his political activities, he was still able to put his poetic abilities to good use, and wrote “The Marching Song of the Irish Volunteers.”

In March of 1915, he was appointed commandant of the 2nd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Volunteers. MacDonagh was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B.) in 1915, and believed, as many did, that “zealous martyrs” would be the ones to secure Irish freedom. He did not join the I.R.B.’s Military Council until April 1916, so he had little part in planning the Easter Rising, though some believe MacDonagh contributed much to the language of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

During the Rising, MacDonagh commanded the garrison at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory, and was initially reluctant to comply with Pearse’s order to surrender. He was court-martialed on May 2 and executed by firing squad the following day at Kilmainham Gaol. – Julia Brodsky

Con Colbert

October 19, 1888 – May 8, 1916

Cornelius “Con” Colbert was born in Moanlena, Co. Limerick, into a family with nationalist leanings and Fenian connections. His parents were Michael and Honora (née MacDermott) Colbert. The young Con did not deviate from his pedigree and became a fluent Irish speaker after he joined the Gaelic League. He later rose through the ranks of Na Fianna Éireann, the nationalist youth organization founded by revolutionary nationalists Bulmer Hobson and Constance Markievicz.

Colbert excelled in the arts of drilling and marching, and was recruited by Pádraig Pearse to be a drilling instructor for St. Enda’s. Colbert was also enlisted by the I.R.B., and became the leader of a cell comprised only of Fianna members. He was part of the initial leadership of the Irish Volunteers, and led the anti-war faction after John Redmond committed the National Volunteers (who split from the Irish Volunteers) to fighting for the British in WWI.

In the Rising, Colbert and his men began fighting at Watkins’s Brewery. They saw little action there and moved to Jameson’s Distillery. There the battalion did more but still comparatively little fighting. After the surrender he was tried by court-martial, and executed on May 8. As an unmarried man and one of the youngest leaders in the rising who did little fighting, his execution is said to have brought on some of the most bitter recriminations.– R. Bryan Willits

Edward Daly

February 25, 1891 – May 4, 1916

At 25, Edward “Ned” Daly was the youngest leader of the Easter Rising to be executed. Born in Limerick, he was the only son of ten children by Catherine O’Mara and Edward Daly, a prominent Fenian, who died five months before Ned’s birth. His uncle John Daly was an organizer for the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He served 12 years in prison on false possession of explosives charges.

Ned worked as a bakery apprentice and timber yard worker before eventually settling in Dublin at a wholesale chemist shop. There, he lived in with his sister Kathleen, who was married to Thomas J. Clarke. He reinforced Daly’s ideological republican politics.

He joined the Irish Volunteers in November 1913 and was a consummate student of military strategy and was soon one of the youngest military authorities in the Volunteers. By March 1915, he was promoted to commander of the 1st Battalion.

During the Rising, Daly commanded a battalion at the Four Courts. This battalion saw some of the most intense fighting during the week, as it lay on the main route from a British barracks in the west of Dublin to the city center. – Adam Farley

John MacBride

May 7, 1868 – May 5, 1916

Born in Westport, Co. Mayo, to Patrick MacBride, a trader and shopkeeper, and Honoria Gill, John MacBride was educated in Westport and at St. Malachy’s College in Belfast. He later moved to Dublin where he worked as a wholesale chemist. About this time he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

MacBride moved to Transvaal in southern Africa in 1896 to work in the Johannesburg gold mines. When the Second Boer War began the following year, he organized “the Irish Brigade” to fight on the side of the Dutch Boers against the British. He was deemed a British traitor and escaped to Paris, where he met Maud Gonne. They married (though they separated in 1905) and had one son, Sean MacBride.

He returned to Ireland after the pardoning of Boer War militants and settled in Dublin. He served on the supreme council of the I.R.B., but was excluded from the planning meetings for the Easter Rising because of his wartime history. Reportedly, he had no involvement in the Rising until after it began, chancing upon Thomas MacDonagh on Grafton Street the morning of Easter Monday. He volunteered his services and fought at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory. – Adam Farley

Michael Mallin

December 1, 1874 – May 8, 1916

Michael Mallin was born into a Dublin working-class family to John and Sarah (née Dowling) Mallin. He joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1889 and served in India for six years, fighting against insurgent tribes. While there, Mallin became disillusioned with the army and equated the Indian struggle for independence with his own experience as an Irishman.

After serving in the army for twelve years, Mallin returned to Dublin to join the family trade as a silk weaver and soon became an active socialist and labor organizer. In 1914 he was appointed by James Connolly as chief-of-staff of the Irish Citizen Army. He wrote for the Irish Worker and also published articles on guerrilla warfare in the Worker’s Republic. During the Rising, he led an I.C.A. force of about 250 in St. Stephen’s Green. Since James Connolly was fighting in the G.P.O., Mallin became the main commander for the I.C.A. along with Countess Markievicz, whom he chose as his second in command. After the I.C.A. abandoned its position at St. Stephen’s Green, the majority of the I.C.A. occupied the College of Surgeons until the surrender. Mallin surrendered along with a force of 109 men and ten women. He left behind a large family, the youngest member of which was born four months after his execution.– R. Bryan Willits

Michael O’Hanrahan

March 17, 1877 – May 4, 1916

Michael O’Hanrahan (also Miceál Ó hAnnracháin) was born in New Ross and raised in Co. Carlow, where he was educated at the Christian Bothers’ School and Carlow College Academy. His father Richard is said to have taken part in the 1867 Fenian rising. After graduating, he worked briefly for his father’s cork-cutting business before becoming secretary for the Gaelic League, founding the first Carlow branch, and teaching Irish at the Catholic Institute.

By 1903 he had moved to Dublin where he was a proofreader for Cló Cumann, a publisher of Gaelic League literature. He also worked as a freelance journalist, publishing in nationalist newspapers Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteer, and authored two novels, A Swordsman of the Brigade (1914) and When the Norman Came (published posthumously in 1918).

A vocal nationalist from an early age, he joined the Irish Volunteers on their founding and was a member of the I.R.B. around the same time. Eventually he became quartermaster of Thomas MacDonagh’s 2nd Battalion, and he and MacDonagh became close friends. During the Rising, he was third in command, after MacDonagh and John MacBride, of the 2nd Battalion, fighting at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory.

– Adam Farley

Seán (John J.) Heuston

February 21, 1891 – May 8, 1916

Seán Heuston was born in Dublin, the son of John Heuston and Maria Heuston (née McDonald). In 1910 he joined Fianna Éireann, a nationalist youth organization founded by revolutionary nationalists Bulmer Hobson and Countess Markievicz and later became a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. As a close friend of Con Colbert, he helped with drilling instruction at St. Enda’s school. He also took part in landing weapons for the Irish Volunteers in the Howth gunrunning.

Heuston rose to the rank of captain of D Company in Edward Daly’s 1st Battalion of the Irish Volunteers’ Dublin Brigade. When the Rising began, he was assigned commander of the Mendicity Institution, and was charged with controlling the route between the Royal Barracks and the Four Courts. He and fewer than 30 men fought from this position for over two days. They capitulated when they were surrounded by hundreds of troops who came close enough to lob grenades into the building. Heuston is said to have surrendered only to save his comrades’ lives.

As a junior officer and one of the youngest executed, it is presumed that his sentence came as a result of his effectiveness in battle; he and his men held an independent position and inflicted serious losses on the British. – R. Bryan Willits

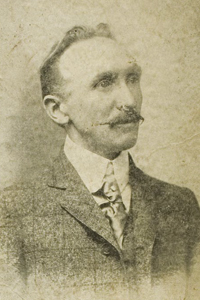

Thomas Kent

August 29, 1865 – May 9, 1916

Along with Roger Casement, Thomas Kent was the only person executed for the Rising who was not in Dublin during Easter Week. He stayed Co. Cork since national mobilization orders had been countermanded. Once the Rising began, the Royal Irish Constabulary began arresting known sympathizers and members of the I.R.B., Sinn Féin, and the Irish Volunteers, of which he, along with brothers Richard, David, and William, was a member. On May 2, the four brothers engaged the R.I.C. in a gunfight. Richard died, as well as killing Head Constable W.C. Rowe. Thomas was court-martialed for the killing of Rowe and executed in Cork.

Born in rural Cork, near Fermoy, Thomas was one of seven sons and two daughters. He was educated at the local national school. He emigrated to Boston, where he spent five years at a publishing and church-furnishing company. He participated in numerous cultural activities there. When he returned to Cork, he was politically active in the Gaelic League. In 1914, he organized the Castelyons branch of the Irish Volunteers with his brothers – the first teetotal branch in the country. – Adam Farley

William Pearse

November 15, 1881 – May 4, 1916

William “Willie” Pearse was born the second son – and the younger brother of the more famous Pádraig Pearse – to James and Margaret (née Brady) Pearse. William studied as an artist and sculptor. He joined the Gaelic League and was a member of the executive of the Wolfe Tone and United Irishmen Memorial Committee.

By 1910 William was teaching art and English at Pádraig’s St. Enda’s school and its sister school, St. Ita’s. Along with Thomas MacDonagh, he insisted that drama should be an integral part of the curriculum. Pearse later founded the Leinster Stage Society and was an actor at the Abbey Theater.

With his brother, he joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and by 1915 was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He was not intimately involved in the planning of the Rising, nor was he subsequently seen to be a principal leader. During the Rising, he served as captain on the headquarters staff in the G.P.O. After the surrender, it was expected he would be released, but he was executed on May 4, the day after his brother was shot. Of the executed, William Pearse was the only one to plead guilty at his court-martial. This, with his family ties to Pádraig, a principal leader of the Rising, is considered to be the primary reason for his execution.– R. Bryan Willits

Excellent educational article on excellent Irish Men who gave their ultimate sacrafice for Ireland.