When Irish exiles needed a refuge, they swarmed to New York and established a hotbed of anti-British sentiment and activity that fed the flames of Irish freedom.

The Great Famine in the 1840s forced millions of Irish out of Ireland, initially flooding the big cities of the east coast of America, especially New York and Boston. New York became a popular target for settlement because it already had an Irish population and a strong leader in Archbishop “Dagger” John Hughes, a man who stood up for his people against threats from the bigoted nativists, such as the Know-Nothings.

The refugees from Ireland came for food and jobs, but they never forgot their homeland. And ironically, by pushing the Irish out of Ireland, to where they could better muster support for revolution, the British guaranteed that in less than seventy-five years, they’d be pushed out of what is now the Republic of Ireland.

From the mid-19th century until Ireland finally staked out its independence, Irish American rebel leaders in New York played a major role in the country’s march to freedom. They raised money, they shipped guns, and they provided a home away from home for any rebel in need of safe harbor or support.

The road to Easter Week began in earnest for New York’s Irish American community in 1859, when John O’Mahony, an exiled veteran of the Young Ireland movement, started the Fenian Brotherhood. This organization was inspired by the Irish Republican Brotherhood – the secret organization that aimed to free Ireland by physical force – that James Stephens had founded in Ireland the previous year. Once the Brotherhood was established, New York became a hotbed of anti-British activity, and it would continue to be one through to the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

The Fenian Brotherhood

The American Civil War turned out to be a crucible for the rebels. New York’s Irish fought for the Union in the Civil War, most famously in the “Fighting” 69th Infantry Regiment, organized by refugees of the failed Young Ireland insurrection of 1848. O’Mahony also organized a regiment of the New York National Guard, the 99th, composed entirely of Fenians. The Civil War proved a tough training ground for these Fenians, but they put what they learned to use, returning to Ireland to fight in the Rising of 1867. Unfortunately, informers betrayed them, and many of them were arrested as soon as they showed up to fight back home.

Devoy Rules from New York

After the ’67 rebellion failed, the British imprisoned many Fenians, among them John Devoy. Upon his release, he made his way to New York in 1871, along with Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and three others who became know as the “Cuba Five,” because they had sailed from Ireland on board the ship Cuba.

Devoy became active in Clan na Gael, the successor to the Fenian Brotherhood, and continued his anti-British activities from his New York base. In 1876, he planned a successful escape for six Fenian prisoners from a Western Australia penal colony on board the ship Catalpa. Devoy said the success of the mission – which at one moment had the Catalpa hoisting the Stars and Stripes to escape a British warship – was due to “a combination of Irish skill and pluck and Yankee grit.” After it, Devoy was able to attract prominent Irish rebels to New York, and following years of activism, Pádraig Pearse dubbed him, “The greatest of the Fenians.”

Tom Clarke, a True New Yorker

Probably the most important rebel to arrive in New York during this time was Thomas Clarke, who immigrated there in the early 1880s. He became an American citizen in Brooklyn in 1883, and would become the only American citizen executed by the British in 1916.

He left New York in 1883 to take part in an ill-conceived campaign to bomb London Bridge and subsequently spent fifteen years in British prisons. When he was released, he returned to New York and struck up a life-long friendship with Devoy – one that would play a vital part in the coming rebellion – and he helped Devoy start his newspaper, The Gaelic American. In 1901, Clarke married Kathleen Daly in New York. John MacBride – another 1916 martyr – was best man, and Devoy was a member of the wedding party. The newlyweds were true New Yorkers, living in Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and later on Long Island where they ran a farm. “New York was as new and interesting to me as anywhere else in America,” Kathleen wrote in her autobiography, Revolutionary Woman.

Then, in 1907, with hopes that an imminent war between Britain and Germany would give Irish rebels better circumstances in which to stage a rebellion, the Clarkes moved to Dublin, where Tom opened a tobacconist shop on the corner of Parnell and Sackville (O’Connell) Streets, under the shadow of the Parnell Monument. The store became a rebel meeting place, where every young Irish revolutionary of the day would come to discuss revolution, among them, Seán MacDiarmada, Pearse, Joseph Mary Plunkett, and even the young Michael Collins.

John Kenny’s Fenian Ram

John Kenny, from County Kildare, was another Irish expatriate who came into Devoy’s sphere of influence in New York. Kenny became a member of Clan na Gael and served as the organization’s president on several occasions. A brilliant businessman, Kenny was instrumental in the Catalpa rescue, and later financed one of the first attack submarine prototypes, John Holland’s Fenian Ram. The vessel is now housed at the Patterson Museum in New Jersey, and is probably the only submarine – not yellow – to have had a song written about it, The Wolfe Tones’ “The Great Fenian Ram.”

Kenny, who remained active in the Land League, swore Tom Clarke into Clan na Gael and was responsible for choosing him for a “special mission” in England. This turned out to be a bomb attack on London Bridge, but Clarke was caught and did time. Years later, when Clarke resigned from The Gaelic American, Kenny took over as business manager.

When W.W.I. broke out, Kenny traveled to Europe, to enlist Germany’s support for Ireland’s fight for freedom and, in the two years leading up to 1916, he couriered money between New York and Dublin for the leaders of the Rising. He died in New York in 1924.

The Fenian Odd Couple

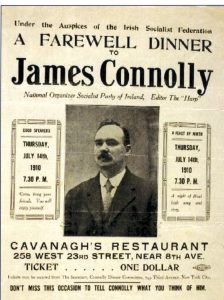

In the years just prior to the Easter Rising, many prominent rebels passed through New York and Devoy made key friendships with the men who would soon start the revolution. One of them, James Connolly, lived in the New York area from 1903 to 1910, and became a full-time organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (the “Wobblies”). One his return to Ireland, he succeeded Jim Larkin as head of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in Dublin.

Pádraig Pearse came in March 1914 and visited Devoy at his newspaper office on William Street. While in New York, he attended a Robert Emmet commemoration in Brooklyn. Using words that proved prophetic, he told those gathered, “We owe to our country all fealty and she asks always for our service; and there are times when she asks for us not ordinary but some supreme service.”

Another visitor to New York was Sir Roger Casement, and if ever there was ever a Fenian odd couple, it was Devoy and Casement. After he had become disenchanted with British rule in Ireland, Casement was keen to join the nationalist movement and wrote anonymous articles for Joseph Mary Plunkett’s magazine, The Irish Review. Even so, Tom Clarke and the Fenian hierarchy in Dublin viewed Casement with suspicion since he was a knighted Protestant. “Casement had come into things national and Tom knew very little about him,” Kathleen Clarke, Tom’s widow, recalls in her autobiography, Revolutionary Woman. “Naturally, he had no cause to place much confidence in him; and the fact that he had been knighted by England in recognition of services rendered made Tom suspicious of him. Casement was not long enough in nationalist things in this country to prove his genuineness.”

Casement had plans – like Kenny – to bring Germany to Ireland’s aid and traveled to New York to share his plans with Devoy in the hopes of a better reception that he’d got from Clarke. But Devoy was skeptical and the relationship never prospered. “John Devoy simply hated him,” Joseph Plunkett’s sister Geraldine wrote in her autobiography, All in the Blood. Oddly enough, in Devoy’s own autobiography, Recollections of an Irish Rebel, he displays a fondness for Casement, something one would not expect from the tough old Fenian jailbird. “He was,” writes Devoy, “withal one of the most sincere and single-minded of Ireland’s patriot sons with whom it was my great privilege to be associated…the soul of honor.”

Although he had his own doubts about Casement’s plans, Devoy introduced him to his German contacts, gave him a large amount of money, and packed him off to Europe to buy guns. That journey would end in disaster when the Aud, with a cargo of German guns on board, was intercepted by the British navy off the Kerry coast, and scuttled by the crew.

O’Donovan Rossa: “Send Him Home”

On June 29, 1915, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, the old Fenian, died on Staten Island. Legend has it that Devoy wired Clarke in Dublin, “Rossa dead. What should I do?” Clarke replied: “Dig him up and send him home!” There, in what was to be one of the great shows of nationalistic theatre, Clarke paraded the body around Dublin, arranged for him to lie in state at City Hall, and gave him a funeral mass at the city’s Pro Cathedral. (Devoy said: “No matter how the Irish treat a leader when living – and the treatment is often very bad – they never fail to give him decent burial”). Thousands followed Rossa’s coffin to Glasnevin Cemetery, where, on August 1, Pearse gave his famous graveside oration, “…the fools, the fools, the fools! – They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.” Rossa’s funeral was the unofficial launch to what would become the Easter Rising eight months later.

Éamon de Valera Hits New York

In one of the most bizarre moves in Irish revolutionary history, Éamon de Valera left Dublin in May 1919 for an almost two-year-long speaking tour of America. He arrived in New York in June and was fêted by Devoy and his friends at the old Waldorf Astoria Hotel on 34th Street (now the site of the Empire State Building). De Valera’s rationale for leaving his country in the midst of a revolution was to get support for establishing Ireland as a republic and to raise money for the emerging nation.

At first, Devoy and de Valera got on famously. Devoy even went so far as to comment that he was “the best leader that Ireland has had for a century.” But things went downhill quickly.

Devoy and de Valera famously butted heads on how a loan for Ireland would be raised. De Valera had formed his own fundraising organization, The American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic, going over Devoy’s head and causing a split in Irish America. By August 1920, Devoy was calling de Valera “the most malignant man in all Irish history!”

Relations between Devoy and de Valera became so toxic that Devoy began referring to Michael Collins in The Gaelic American as “the recognized leader of the fighting men of Ireland.” In his biography of Devoy, Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America’s Fight for Ireland’s Freedom, Terry Golway notes that, “Devoy would later write that had it been up to him, he’d have had de Valera shot rather than waste the government’s time and money with a mere prison sentence.”

Coincidentally, one month and two days after Collins’ men shot up the British Secret Service in Dublin, de Valera left New York for home. Did he think perhaps the tide of the war had turned in favor of the rebels – and that they would need him to make peace? If that was his motivation, then the narcissism that Devoy had despised in de Valera was fully in evidence. And given Devoy’s antipathy to the future president of the Republic, he would have let everyone in the Irish American rebel community know. And who would begrudge “the greatest of the Fenians” his opinion, given that he had rallied this New York rearguard, for so long and so well in the cause of freedom. ♦

_______________

Dermot McEvoy is the author of the The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at dermotmcevoy50@gmail.com. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com.

Wouldn’t it appear that Devoy was equally self-regarding as deValera ever was, from the confrontation between them ? Why should Mr McEvoy suggfest otherwise ?