Michael Collins was born into a farming family near Clonakilty in County Cork in 1890. In 1906 he passed a civil service exam and went to London to work in the British postal system, which included the banking and communications sections – an invaluable learning experience for the future Minister for Finance in the first Dáil. While in London, Collins joined the usual Irish organizations such as the Gaelic League and Gaelic Athletic Association. It was in 1909 that Sam Maguire, also from Cork, swore him into the Irish Republican Brotherhood, setting him on the path to revolution. It is in the latter part of 1915 that the mystery surrounding the romantic figure of Collins begins to emerge.

Most of Collins’s biographers have him returning to Dublin in January 1916 to begin preparations to fight in the Easter Rising. But he actually returned in late summer 1915 and went to work for Joseph Mary Plunkett, straightening out the family’s real estate investments which had gone awry under the eccentric Countess Plunkett. At this time he came under the tutelage of the likes of Tom Clarke and Seán MacDiarmada, the two main organizers of the upcoming rebellion. On Easter Monday he served as aide-de-camp to Commandant-General Plunkett, who was dying at the time of tuberculosis of the neck glands.

Collins would escape the burning G.P.O. on Friday with the rest of the Volunteers and find refuge in Moore Street. Though he participated in the Rising, he was skeptical of it. “I do not think the Rising week was an appropriate time for the issue of memoranda couched in poetic phrases, nor of actions worked out in a similar fashion,” he wrote from the Frongoch prison camp in Wales. “Looking at [the G.P.O.] from inside it had the air of a Greek tragedy about it.” He realized that the way to beat the British was not to have big military battles with the finest army in the world. Another form of warfare – and intimidation – would have to be used.

Along with the rest of the rebels, he surrendered to the British and was marched up Sackville Street to the garden of the Rotunda Maternity Hospital in Parnell Square. Arguably, it was here that Collins first learned the importance the British paid to the use of intelligence and he vowed to match them in this science. It is also here that one can see the young Collins begin to plot future strategy. He saw members of the G-Division, the intelligence sector of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, begin to separate Fenians according to their importance. He saw them abuse Seán MacDiarmada, a victim of polio, and strip naked Tom Clarke. Collins secured the name of MacDiarmada and Clarke’s abuser, Deputy Inspector Percival Lea Wilson. Three years later Wilson would be gunned down by Collins’s Squad in Gorey, County Wexford.

Collins spent the rest of 1916 in British prisons and at Frongoch before being freed that December. In early 1917, he was appointed head of the National Aid and Volunteers Dependants Fund by Tom Clarke’s widow, Kathleen. The N.A.V.D.F. was a charity for indigent members of the Volunteers and their families, but for Collins it was more. It was a way to meet rebels from all over the country and plan for the future. It was a way to ensure that the first person a rebel from the countryside would meet in Dublin would be Collins himself, a fellow “culchie.” Collins spent 1917 and 1918 organizing the newly formed I.R.A., campaigning for Sinn Féin members to parliament, opposing conscription, and reviewing his options for dealing with the G-Division of the D.M.P.

De Valera Leaves — Guerrilla Warfare Arrives

The lives of Collins and Eamon de Valera are intimately connected by the decisions de Valera would make between 1919 and 1922. In May 1919, de Valera decided that the place for the head of a revolutionary movement was not in Dublin, but America. He arrived in New York to bring word of Ireland’s struggle to the world and to raise funds for the nascent nation. His vacuum back in Dublin was to be ably filled by his robust Minister for Finance.

Hayden Talbot’s Michael Collins’ Own Story gives an inside look at Collins’s thinking during this time. The book, supposedly, was to be Collins’s autobiography, but he died before it was published. In it, Collins maintains the biggest problems facing the insurgents were twofold: “beating the English Secret Service until it was powerless” and “cleaning our own house until the last traitor Irishman had been identified and fittingly dealt with.” To bring this about Collins opened an intelligence office at 3 Crow Street – a little alley running off Dame Street and only two blocks from Dublin Castle – under his Deputy Director of Intelligence, Liam Tobin. Here dossiers were collected on every member of the G-Division and movements of suspicious strangers were monitored with the help of sympathizers in the railroad, shipping, taxis, and hotel industries. Unsurprisingly, Tobin also found that sometimes the best way to keep track of enemy agents was through the society pages.

In a parallel move, Collins set up in September 1919 his own Active Service Unit known simply as “the Squad,” or more colorfully as “The Twelve Apostles.”

At first the G-men were warned to leave. If they did not, they were roughed up. If they still persisted, they were shot. During 1920, there were specific shootings that caught the eye of the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill. One was the assassination of a British spy nicknamed Jameson, who got close enough to Collins to see he was wearing a mustache. The other was the elimination of Alan Bell, who was searching the banks, looking for Collins’s National Loan. Bell was pulled off a tram by the Squad and shot. Collins observed that there were no more bank examiners rushing to Dublin to find the National Loan money. The shootings of Jameson and Bell precipitated Churchill rushing the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans into Ireland to maintain peace. He also put a £5,000 bounty on Collins.

The biggest blow to the British happened on the morning of “Bloody Sunday,” November 21, 1920, when the Squad shot fourteen members of the British Secret Service. “There is no crime,” Collins wrote of that fateful day, “in detecting and destroying in war-time, the spy and the informer. They have destroyed without trial. I have paid them back in their own coin.”

De Valera Returns

One month and two days after Bloody Sunday, Eamon de Valera returned from America. By July 1921, King George V had finally managed to arrange a truce. The truce came at an ideal time because after the I.R.A. burning of the Customs House in May 1921 – which ended with five I.R.A. members killed and over 80 taken prisoner of an estimated 100 who participated – Collins knew that the I.R.A. in Dublin was on its last legs. De Valera went to London to meet British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. In preliminary discussions, Lloyd George made it clear that a Republic was out of the question, but he could settle for an Irish Free State which would complement the newly established six-county government of Northern Ireland. There would also be an Oath of Allegiance to the King. De Valera went back to Dublin to plot.

It was a delicate negotiation process that de Valera knew would be a no-win for him if he wanted to stay in power. According to Tim Pat Coogan’s biography of de Valera, he was heard commenting of the plenipotentiaries: “We must have scapegoats.”

Ultimately, he persuaded Collins to lead the delegation in his stead. Collins resisted – he knew that he could not bring back a Republic. “To me the task is a loathsome one,” Collins wrote. “I go in the spirit of a soldier who acts against his best judgment at the orders of his superior.”

Collins was wary of the whole deal. In London he brought his own staff and even lived apart from the rest of the delegation. He was highly suspicious of Erskine Childers, secretary to the delegation, who he was sure was a de Valera spy. The negotiations dragged on for a month without any progress. One night with their meetings going nowhere, Churchill suggested they return to his townhouse for drinks before continuing work on the Treaty. Collins and Churchill proceeded to drink a lot of cognac (Collins liked his spiked with Curaçao to keep his sweet tooth sated) and the talk turned ugly. At one point Collins reportedly exclaimed, “You put a £5,000 bounty on my head!” to Churchill. Churchill, years later, wrote that “[Collins] was in his most difficult mood, full of reproaches and defiances, and it was very easy for everyone to lose his temper.”

Churchill took him by the hand to the other end of the room to show him a wanted poster. It was for the young Churchill in the Boer War. “At any rate it was a good price – £5,000,” said Churchill. “Look at me – £25 dead or alive. How would you like that?” Collins roared with laughter, the tension was broken, and on December 6, 1921 Michael Collins signed the Treaty creating the Irish Free State. Collins knew that to give Ireland life he had most likely to pay with his own. “Think – what have I got for Ireland?” he wrote. “Something which she has wanted these past 700 years. Will anyone be satisfied with the bargain? Will anyone? I tell you this – early this morning I signed my own death warrant.”

The Treaty and the Oath of Allegiance

In early January 1922 the Dáil began to debate the Treaty. It came down to Collins vs. de Valera. Collins viewed the Treaty as a vehicle. “In my opinion,” he wrote, “it gives us freedom, not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire … but the freedom to achieve it.” De Valera viewed the Treaty as a failure because it did not bring back a Republic. There was also the problem of the oath of allegiance to the king. It was mandatory that all members of the Dáil had to take the oath. This was verboten to de Valera and his followers, people like Cathal Brugha and the Countess Markievicz. “Deputies have spoken about whether dead men would approve of it,” said Collins during the Dáil debate, “and they have spoken of whether children yet unborn would approve it, but few have spoken of whether the living approve it.”

De Valera and his loyalists plotted every parliamentary trick they could to derail the Treaty, frustrating and infuriating Collins to no end. “We will have no Tammany Hall methods here!” shouted Collins in the Dáil. “Whether you are for the Treaty or whether you are against it, fight without Tammany Hall methods. We will not have them.” Not getting their way, de Valera and cohorts deserted their duty as the loyal opposition and marched out of the Dáil. The Dáil passed the Treaty by a vote of 64 to 57 and Ireland, finally, was a nation once again – albeit a nation in civil war.

Death at Béal na mBláth

Because of de Valera’s withdrawal, Collins and Arthur Griffith were left to run the country. Griffith became President of the Dáil and Collins ran the army as he continued to work with the British over the transferral of government agencies. In April, anti-Treaty forces took over the Four Courts in Dublin. Collins, because he had so many friends among the anti-Treaty forces, did not immediately react. He wanted to find a way out through negotiations. He waited two months, until under pressure from Churchill, he blasted them out. Large sections of the country had to be retaken by the new Free State army, particularly in the west and in the south.

Things were seemingly beginning to coalesce for the new government when President Griffith suddenly died on August 12th from a cerebral hemorrhage. The weight of the nation once again fell on Michael Collins’s shoulders. Collins, still looking for a mediated settlement to the Civil War, decided to travel to his home county – strongly hostile to the Treaty – to not only show the flag, but to politic among the locals. Also, it was known that de Valera was also in the vicinity. Perhaps a settlement could be reached? When told he was a fool to go to rebel Cork, Collins reportedly replied, “Yerra, they’ll never shoot me in my own county.”

On August 22nd Collins and his entourage traveled the back roads of West Cork, stopping in pubs to talk with the locals. In the early evening at a road called Béal na mBláth – “the mouth or the gap of the flowers” in Irish – shots rang out. “Drive like hell!” shouted General Emmet Dalton, his traveling companion.

But Collins would have none of it: “Stop! Jump out and we’ll fight them.” Minutes later he was dead from a bullet wound to the back of his head. Seán O’Connell, a member of the entourage, whispered an act of perfect contrition into the General’s ear. Collins’s service to his country was finished.

Michael Collins Today

At his last meeting before traveling for Béal na mBláth Collins told Churchill, “I shall not last long; my life is forfeit, but I shall do my best. After I am gone it will be easier for others.” But it was not easy – the Civil War would last until 1923 with terrible atrocities committed by both sides, polluting the political waters of Ireland for the rest of the 20th century.

With Collins’s death, de Valera’s star began to rise. In 1927 he entered the Dáil and, in the hypocrisy of hypocrisies, took the oath of allegiance. By 1932 he was the President once again and slowly but surely the figure of Michael Collins was airbrushed out of Irish history. Then, 50 years after his death, there was a resurrection. Margery Forester wrote a wonderful biography called Michael Collins: The Lost Leader, which brought Collins alive to a new generation of Irish. She was followed by new and thorough biographies by the likes of Tim Pat Coogan and T. Ryle Dwyer. With these books the Irish rediscovered their Dublin Pimpernel, a man who made James Bond look foppish. Then Hollywood came calling with Academy Award winner Liam Neeson filling the big screen with a bigger rendition of the Big Fellow.

What is the legacy of Michael Collins today? Most would say that it is rather simple: he found a way to beat the British and in doing so returned nationhood – albeit an imperfect nationhood – to the Irish people.

Perhaps the greatest salute comes from his old antagonist, Eamon de Valera: “It is my considered opinion that in the fullness of time history will record the greatness of Michael Collins and it will be recorded at my expense.” ♦

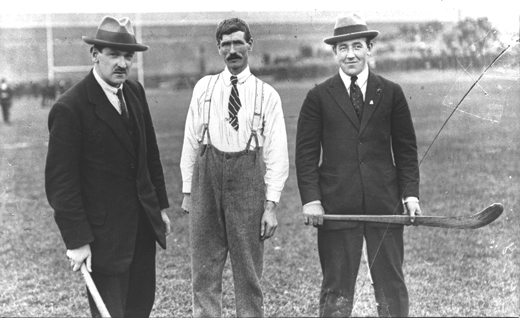

A statue of Michal Collins is unveiled in Clonakilty, Co. Cork and Liam Neeson was there to share his appreciation of the great revolutionary.

Dermot McEvoy is the author of the The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at dermotmcevoy50@gmail.com. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com.

Note: This article was originally published in the February / March 2016 issue of Irish America.

Wonderful piece! Thank you