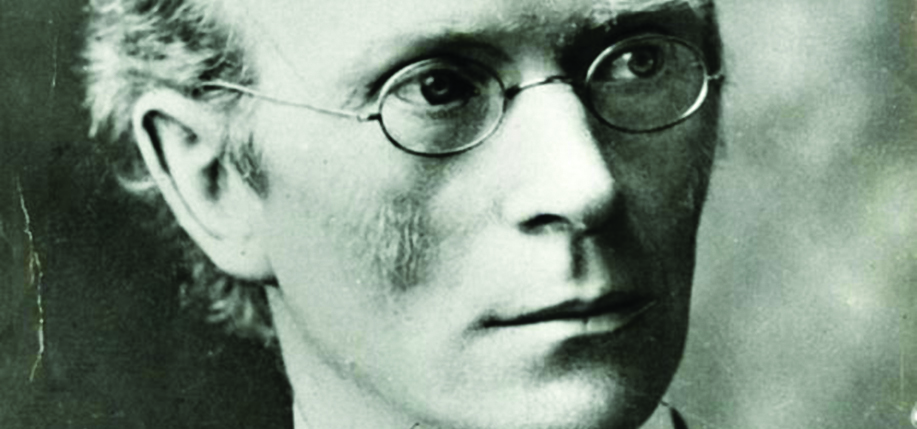

Eoin MacNeill (pictured above) tried to stop the Rising, but there would have been no Rising without him. Maureen Murphy writes that it’s time to reevaluate the role of this true Irish patriot.

When it comes to the Easter Rising, Eoin MacNeill (1867 – 1945) is generally dismissed as the man who canceled the mobilization of the Irish Volunteers for Easter Sunday 1916, a mobilization that masked the start of the Rising planned by members of the clandestine Irish Republican Brotherhood who rose to leadership positions in the Volunteers. While there is debate about the consequences of MacNeill’s countermanding order, there is no question that there would not have been a Rising without MacNeill and the two nationalist organizations he founded: the Gaelic League and the Irish Volunteers.

As a boy in the Glens of Antrim, MacNeill heard a few words of Irish from an old family nurse, but he did not take up the serious study of the language until he was in his mid-twenties working as a clerk in the Accountant General’s office in Dublin. In 1890, while studying Old Irish with Edmond Hogan, S.J., he began Modern Irish with the meager resources were available at the time. He quickly concluded that best chance to learn Irish as a spoken language was to go to the Gaeltacht and learn the language from native speakers. An introduction to Father Eugene O’Growney (1863 – 1899), Professor of Irish at Maynooth College, was the beginning of a friendship that would last for the rest of O’Growney’s brief life. O’Growney directed MacNeill to the Inishmaan home of Paidín and Brighid MacDonnchadha, who had hosted continental Celtic scholars and would later welcome John Millington Synge.

While learning Irish and taking part in local events on Inishmaan, MacNeill learned that the bitterness over the Parnell debacle had even reached the Aran Islands. Years later, in a 1942 radio talk, MacNeill spoke of the opportunity when the crisis split the Irish Parliamentary Party over its chairman Charles Stewart Parnell (1846 – 1891), having been named the correspondent in divorce proceedings was denounced from the altar. The Parnell debacle provided an opportunity for the Gaelic League to replace political nationalism with cultural nationalism. While Douglas Hyde (1860 – 1949), first President of the Irish Free State, is often given credit for the founding of the Gaelic League based on his 1892 speech “On the Necessity for the De-Anglicizing the Irish People,” both O’Growney and MacNeill had written essays that anticipated Hyde: O’Growney’s “The National Language” (1890) and MacNeill’s “Why and How the Irish Language is to be Preserved” (1891). MacNeill followed his essay with “A Plea and a Plan For the Extension of the Movement to Preserve and Spread the Gaelic Language in Ireland” (March 1892), and he circulated a notice to those he thought might be interested in attending a meeting on July 31, 1893, to discuss the formation of the Irish language organization that he envisaged. Hyde was elected President of the League while MacNeill took on the more demanding office as Secretary and was, for the first ten years of the League, its indefatigable organizer, propagandist, and editor of the League paper An Claidheamh Soluis.

It has become a historical commonplace to call the Gaelic League a social revolution. Sean O’Casey dismissed the League as a respectable, middle-class, Catholic Gaelic organization in Drums Under the Window; however, it was not so narrow. A shared interest in the Irish language crossed class, gender, and religious lines, and the League’s social programs and summer schools brought language enthusiasts together. In fact, the League was twentieth-century Ireland’s first adult education movement. Believing as he did that Irish nationality was based on its native language, MacNeill believed that the Irish language would result eventually in Irish independence. The language movement that was especially attractive to nationalists like Pádraig Pearse (1879 – 1916), who met MacNeill through the Gaelic League and became the longest serving early editor of the League paper (1903 – 1910).

MacNeill’s work for the Gaelic League led to his founding the Irish Volunteers in 1913, two years after Unionists in Northern Ireland founded the Ulster Volunteers whose purpose was to resist Irish Home Rule.

MacNeill responded to the Ulster Volunteers by saying that “Unionists as well as nationalists are determined to have their own way in Ireland.” His article “The North Began,” published in An Claidheamh Soluis on November 1, 1913, proposed that a nationalist volunteer force to be founded all through the country. The I.R.B. or physical force nationalists urged MacNeill to establish such an organization, and the Irish Volunteers were launched at the Rotunda Rink (now the Ambassador Theatre) on November 23, 1913, two days after the founding of James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army. Volunteers signed a pledge promising to “secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland without distinction of creed, class or politics.” About 10,000 Irishmen joined the Volunteers by the end of the first year. A Volunteer triumph occurred when a successful delivery of 1,500 German rifles arrived at Howth and was distributed to the Irish Volunteers on July 26, 1914 just five days before World War I began on August 1st.

Almost three weeks later, John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, spoke to East Wicklow Volunteers at Woodenbridge on September 20th. He called on the Irish Volunteers to enlarge their mission from that of an Irish defense force to a force that would go “wherever the firing line extends, in defense of right, of freedom and of religion on this war.” It was, in fact, a call to the Irish Volunteers to enlist in the British Army. The result was a split within the Volunteer forces, with the majority of Irish Volunteers supporting Redmond’s National Volunteers, and a minority remaining with MacNeill in the Irish Volunteers.

Invoking the old saying that “England’s misfortune is Ireland’s opportunity,” the I.R.B. members who controlled the military council of the Irish Volunteers began to plan for a rebellion while the British were fighting in Europe. It is probable that plans for an Easter Sunday, 1916, rebellion were in place before the end of 1915. The military council neither consulted nor informed MacNeill about their plans. MacNeill, who was critical of the pagan heroism of the cult of Cúchulainn that obsessed Pearse, saw the Volunteers as a civil defense organization that would be called up were there an invasion of the island or were the British to enforce conscription. Pearse and his militant colleagues saw the Rising as an opportunity to inspire Irish people with their heroic blood sacrifice suffered in a Rising that had no chance of succeeding.

On Holy Thursday, when MacNeill learned that the plans for an Easter Sunday mobilization would be the start of a Rising, he told Pearse he would do everything short of ringing up Dublin Castle to stop what he believed would be a senseless and doomed coup d’état. The militants counter with two arguments in favor of going ahead with the Rising. The first was a Dublin Castle “document,” probably the work of Joseph Plunkett, purporting to be a list of nationalists, including MacNeill, who the British planned to arrest. Such a plan would be a just cause for calling out the Volunteers. In addition to the Castle “document,” the militants told MacNeill that a shipment of German arms organized by Roger Casement was heading for Kerry. (The British, who had broken the German code, intercepted the attempt to deliver the weapons.)

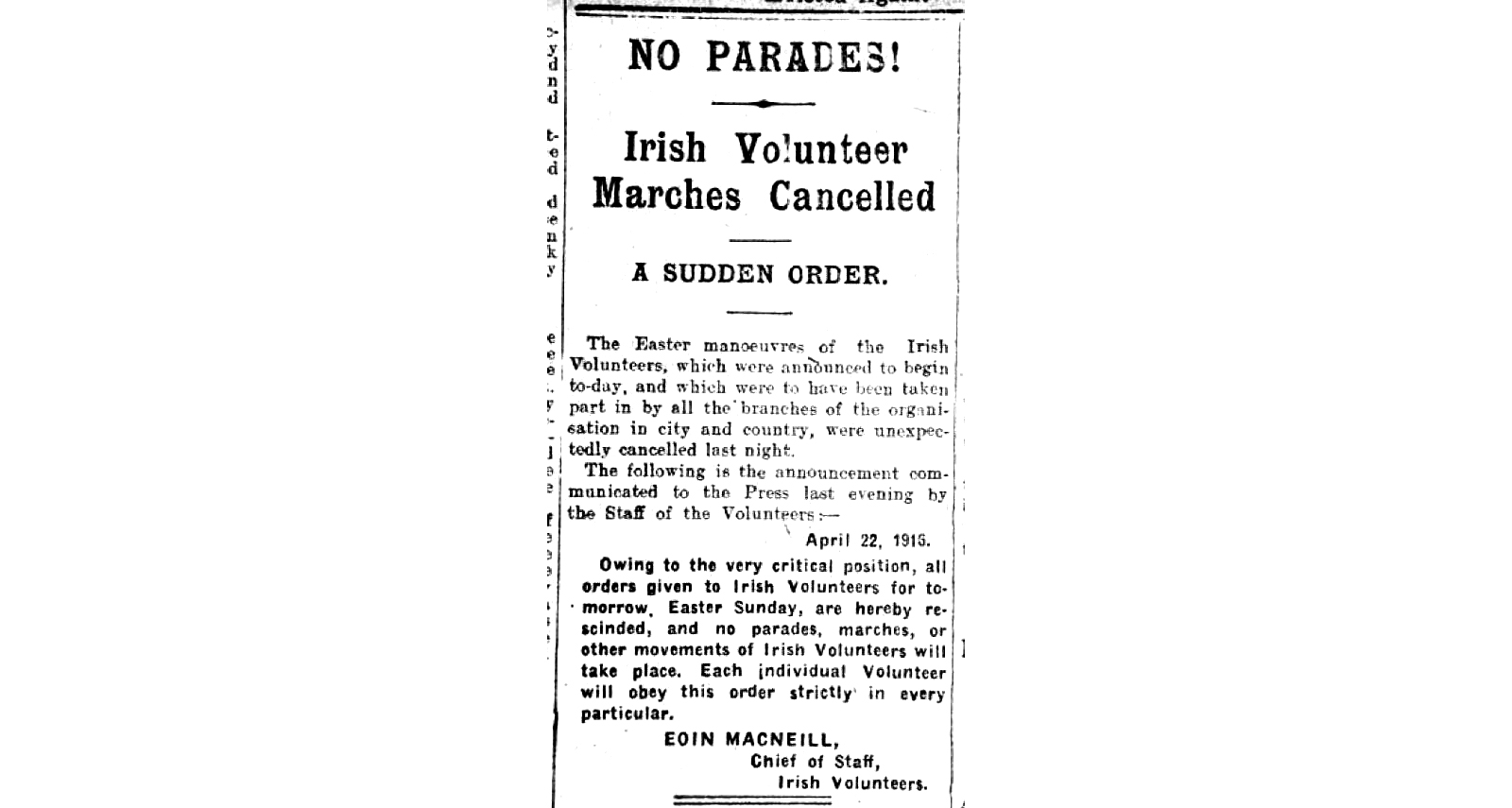

When MacNeill learned that the Castle “document” was bogus and that the arms had been scuttled and Casement arrested, he sent a countermanding order for the Easter Sunday mobilization to be printed in the Sunday Independent and sent messengers throughout the country to advise the Volunteers of the cancellation. As Professor of Early Irish History, MacNeill was committed to an historiography based on primary sources and was distrustful of romantic nationalism; his countermanding order was an attempt to prevent a romantic revolution that had no chance of success. There was no mobilization on Easter Sunday; however, the militants decided to go ahead with the Rising on Easter Monday.

MacNeill did not go out in 1916, but he was arrested with the leaders, tried, and sentenced to life imprisonment. Released in general amnesty of 1917, MacNeill and members of his family were active in the War of Independence. He was elected as a Sinn Féin deputy for Derry. He was sent to prison again from November 1920 to June 1921. As speaker of the 2nd Dáil, he chaired the Treaty debates, and when the Republicans rejecting the Treaty led to Ireland’s civil war, MacNeill’s second son Brian joined the Republican side and was killed on the slope of Ben Bulben in October 1922. MacNeill served as Minister for Education in the first Free State government and was a reluctant member of the Boundary Commission. When the results of the Commission determined that the boundary would remain unchanged, MacNeill resigned from the Commission and from the government, returning, with some relief, to academic life. He was the founding chair of the Irish Manuscript Commission and chaired all of the country’s scholarly organizations. As a scholar, MacNeill is acknowledged to have been the founder of modern study of Irish history. The historian Francis John Byrne has described MacNeill as “having dragged Celtic Ireland practically single-handed from the antiquarian mists into to the light of history.” When he visited the United States in 1930, he encouraged American universities to study Irish history and language informed by those same primary sources.

It was not until the 1960s, when F.X. Martin published MacNeill’s memorandum about 1916, that a reassessment of his role began. As Irish and Irish American communities observe the centenary of the Rising, questions of legitimacy and necessity are inevitable. Central to these considerations will be a re-evaluation of the role of patriot, historian, and Gaelic Leaguer Eoin MacNeill. ♦

_______________

Dr. Maureen Murphy is Fulbright Fellow at University College, Dublin, and is the Chair of New York’s 2016 Commemorations Committee.

Very interesting account of McNeill.

Great article

I too researched Eoin MacNeill for my college senior project and also concluded that Mr. MacNeill deserved more recognition. The Easter rising was doomed especially due to the sinking of the German Ship Aud and the volunteers having limited arms. The British were tipped off.

Thanks for bringing attention to this.