The battle for the hearts and minds of the Boston Irish took a sharp turn in the aftermath of the 1916 Irish Rising.

Prior to the 1916 Rising, Boston’s Irish community had maintained some equilibrium between those who favored constitutional methods of Home Rule, and those for physical force and agitation. And within this spectrum were viewpoints about socialism and worker’s rights, women’s suffrage, Celtic mythology, and cultural revivals as antidotes for Ireland’s woes.

In Boston, dozens of Irish organizations and political activists were on hand to support every perspective. You had the Ancient Order of Hibernians and Clan-na-Gael tending toward physical force, and the United Irish League of America and Charitable Irish Society urging moderation. Many of the two dozen county clubs were actively involved in both. In Charlestown, the Charles Stewart Parnell Literary Club kept the Home Rule leader’s memory alive, and the John Boyle O’Reilly Club had active branches from Boston to Springfield. The newly formed Friends of Irish Freedom opened a Boston branch on April 19, just a week before the Irish Rising.

And you had a colorful cast of characters such as James Michael Curley, the audacious, outrageous Mayor of Boston who hammered away at England’s rule of Ireland while also gloating at the demise of Boston Brahmins who had kept the Irish down for so long. Former mayor John F. Fitzgerald, grandfather to President John F. Kennedy remained influential through his weekly Catholic newspaper, The Republic. You had William Cardinal O’Connell, an ambitious first generation Irish American described by historian James M. O’Toole as a militant Catholic. And dozens of Irish-American orators and organizers stood ready to engage in the propaganda battle for defining what was right for Ireland.

But the equilibrium began to shift with the onset of World War I in 1914, and Bostonians who cared about Ireland’s wellbeing had become increasingly concerned. Ireland’s Home Rule movement was put on hold as the British fought a bloody war with the Germans. Irish men and boys were being recruited to fight and die in trenches on the continent. War taxes were being levied amidst high unemployment and poverty. Draconian laws such as the Defense of the Realm Act allowed authorities to deport or imprison Irish men and women on unproven charges and to suppress newspapers from criticizing the English government.

When the Irish Rising was initially reported in local newspapers in New England, official versions of the “mob disturbance” were disseminated to the American press from Dublin Castle and from London, raising the antennae of the Boston Irish.

The Boston Globe printed the “official communication” from Dublin shortly after the uprising began. “In the course of the day soldiers arrived from the Curragh and the situation is now well in hand,” the statement read. In other words, this was merely another Irish disturbance that English authorities put down.

The Republic newspaper issued an editorial titled, “Mischievous Work of the Sinn-Féiners in Dublin, Ireland,” calling it “an act of folly and political lunacy.”

On April 29, the Globe ran the official statement of John E. Redmond, who called the Rising an “insane movement” that would return Ireland to “another long night of slavery, incalculable suffering and weary, uncertain struggling.” The Boston chapter of the United Irish League of America fired off a cablegram to Redmond, writing, “No doubt of Irish sentiment in Boston. Ardently supports you and the party.”

But support for Redmond’s constitutional nationalism was quickly eroding in Boston as other news became available. On May 1, the Globe printed the Proclamation in full, providing rationale and context for the rebellion. The Globe ran a mixed-message from writer George Bernard Shaw, who described the Rising as “silly, ignorant, wrong-headed, but honorable, brave and republican.”

The Boston Irish community didn’t need Mr. Shaw, or the United Irish League for that matter, to shape its views of the Rising. The sound and fury of Boston’s Irish diaspora had already reached a high pitch as news spread through the sprawling Irish community via local Hibernian Halls and through the Irish American newspapers such as the Gaelic American and Irish World.

The response was electric. Indignation meetings of 20,000 people were quickly convened on Boston Common and thousands gathered in outlying cities like Lawrence and Lowell, Fall River and New Bedford, North Attleboro and Brockton, Worcester and Chicopee, and Springfield, Holyoke and Pittsfield.

In May, when the leaders of the rebellion were executed, the fury reached a new level. In Springfield, 4,000 people held a mass protest and heard inflamed rhetoric from former Boston congressman Joseph O’Connell, Dr. John F. Kelly of Pittsfield, and Judge Cornelius Collins of New Jersey.

On May 14, the Friends of Irish Freedom convened at the sacred Tremont Temple in downtown Boston, where Mayor Curley presided over 5,000 fervent followers, with another 4,000 spilling into Boston Common. Speaker after speaker denounced the English mishandling of the rebellion, and whenever the word Germany was mentioned, a cheer went up from the crowd.

At the Boston Gaelic School rally on Washington Street, the pulpit was draped with an Irish flag, and a white banner of mourning with the word “Vengeance” written in big black letters. “No Irishman with red blood in his veins will rest content until England has been destroyed,” shouted speaker Matthew Cummings.

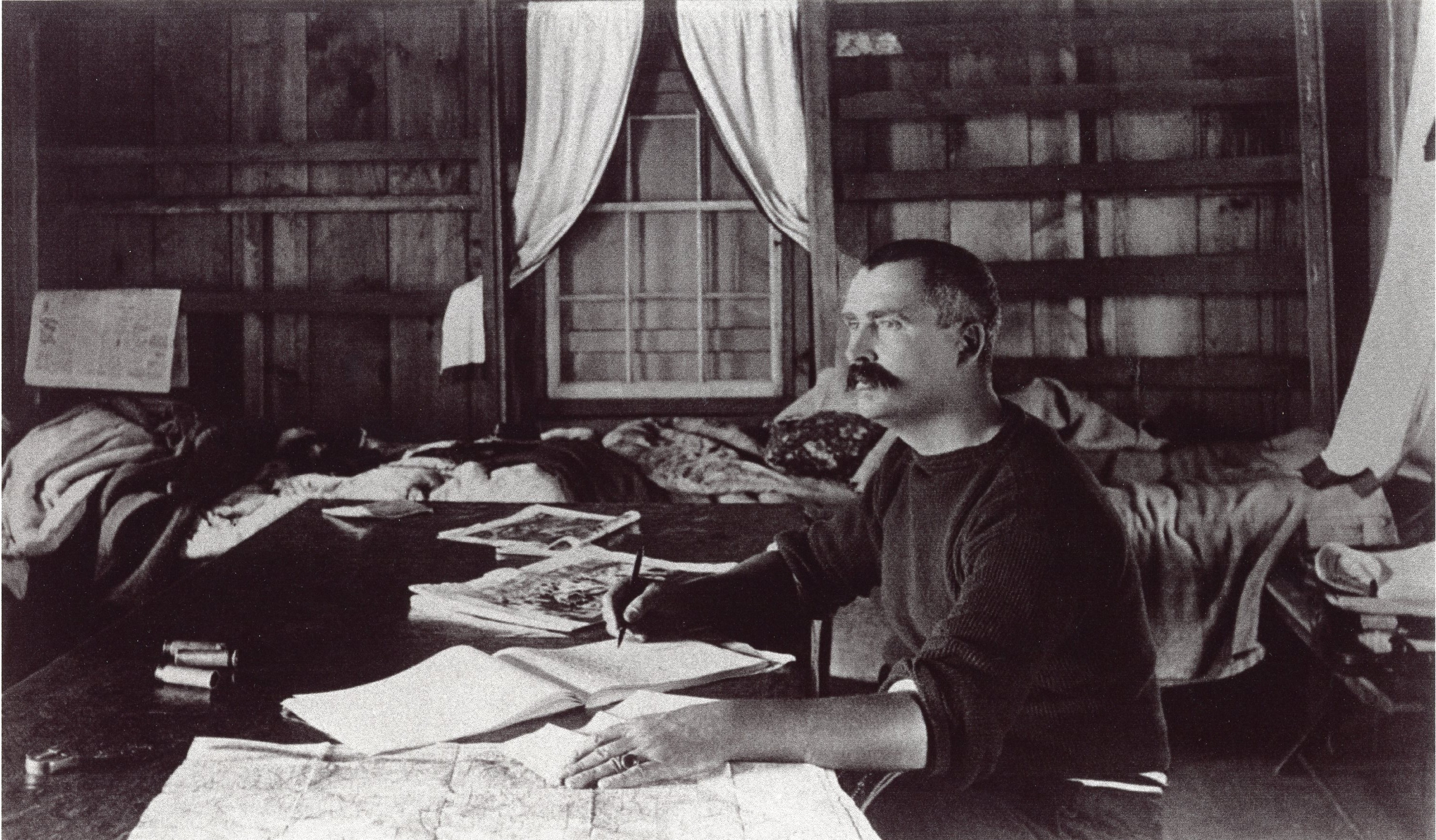

It turns out that many Bostonians knew several key players in the Irish Rising. James Connolly spoke in Faneuil Hall in September, 1902, discussing Irish socialism and worker’s rights, and returned several times before his death, living for a few months in Roxbury’s Mission Hill district. Union leader James Larkin spoke at Tremont Temple in February 1915, and was recalled by the Globe as “more of a poet and an idealist than a red-handed agitator.” Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a militant pacifist who was murdered by a British soldier in the early days of the uprising, visited Boston and Worcester in 1915, espousing women’s rights, vegetarianism, and Irish independence.

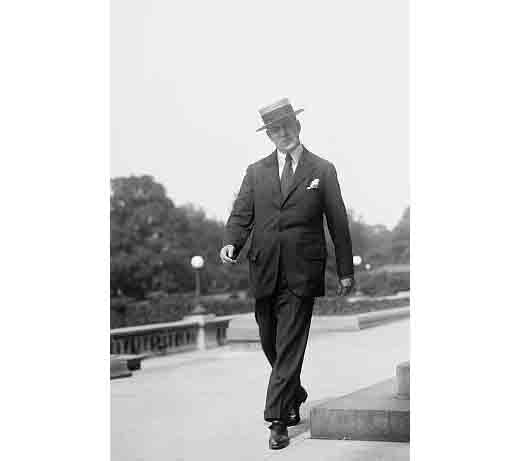

In Boston, no Irish leader suffered a greater reversal of fortune than John Redmond, the Wexford-born British Parliamentarian who had devoted his life to the Home Rule cause. When he first visited Boston in 1884 as a 28-year-old wunderkind, John Boyle O’Reilly himself introduced Redmond to 5,000 people jammed into the Boston Theatre and compared him to Parnell. The cheering lasted several minutes before Redmond was able to speak.

But after the 1916 Irish Rising, Redmond was denounced as a traitor and as a recruiting sergeant for the British Army. Audiences hissed when his name was mentioned, and he became the whipping post for all the perceived wrongs of Ireland.

At a rally in Pittsfield, Justice Daniel Cohalan said, “Can one imagine a more contemptible figure than Redmond? Lost to all sense of decency, he alone has been acting as the chief recruiting sergeant for England in Ireland, but now in the hour of crisis he calls upon his deluded followers to take part with England’s gunmen in shooting down their fellow countrymen who are fighting for freedom.”

In the months after the Rising, Boston became a hotbed for a pitched public relations battle – some would call it a propaganda war – for the hearts and minds of the American public.

The United Irish League remained a notable local Redmond supporter, but even it had to condemn the English for their “deplorable mishandling of the participants of the revolt.” The U.I.L. was joined by an odd mishmash of pundits condemning the revolt. There was Shane Leslie, described by the Globe as “a brilliant Irish journalist” who chimed in while vacationing in Vermont, “The best advice I can give Irish Americans in the present crisis is to back Redmond, as they would back Ireland itself.”

There was L.G. Redmond-Howard, nephew of John Redmond, who was in town to peddle his new book, Six Days of the Irish Republic, a first-hand account of the Rising. The Globe gave him a full page of coverage.

The quirkiest critic was Rev. Dr. William Harman van Allen, an obscure minister who dabbled in family research at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Preaching from the pulpit of the Church of the Advent in Back Bay, Allen said the real criminals were “the American citizens who across 3,000 miles, poured their poison into the hearts and ears and minds of these poor young men and gave them money.”

Contrast these law and order supporters with proponents of the rebellion, like Mayor Curley and former Congressman Joseph O’Connell, along with respected leaders of major Irish organizations. When the A.O.H. held its National Convention in Boston that July, leaders sent an angry cablegram to British Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, denouncing the execution of the rebels.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra performed a free concert for Clan na Gael in June to raise funds for widows and orphans. The 50-person orchestra opened the concert with Beethoven’s march, “Dead Heroes.”

Captain Henry C. Hathaway attended the New Bedford rally and lent his support for the rebellion. He helped rescue John Boyle O’Reilly from the prison camp in Freemantle, Australia, and later hatched a plan to free Fenian prisoners in 1875.

And you had the women of Ireland. In July 1916, Nora Connolly, daughter of executed leader James Connolly, arrived in Boston to tell her father’s side of the story. The smitten Globe reporter, M.E. Hennessy wrote, “She is a sweet little woman of 23, but she doesn’t look over 18. Dressed in black, wearing a large felt picture hat, this little Irish girl tells the story of the uprising and her part in the stirring events with the modesty of a school girl. Miss Connolly is a pronounced brunette. Her features are small, but finely chiseled. She is a charming conversationalist and tells her story in a way that grips the heart strings.”

Connolly was sturdier than described. She said that Irish people “don’t fear to speak of Easter week. They sing it loud and shout it defiantly at the English soldiers and are willing to take the consequences.” She then recited this verse to the reporter:

Who fears to speak of Easter week,

Who dares its fate deplore

The red-gold flame of Ireland’s shame

Confronts the world once more.

Before heading down to New Bedford and New York, Connolly “called on Mayor Curley to pay her respects,” wrote Hennessy. “After a brief chat with the young lady, the Mayor handed her a substantial purse of money, the gift of a few Friends of Irish Freedom, as the Mayor put it.”

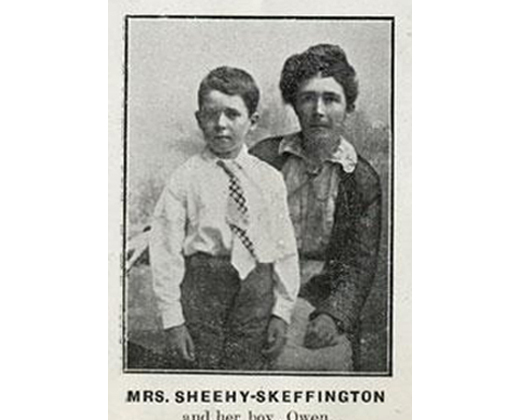

A few months later, Mrs. F. Sheehy-Skeffington and her seven-year-old son Owen arrived in Boston, where she spoke at Faneuil Hall before an overflow crowd. She described how her pacifist husband Francis was murdered by an English soldier during the Rising, and how the English had tried to cover it up. For this trip, authorities threatened to reject her passport unless she agreed “not to talk about the war or conditions in Ireland.” Instead, she and her son smuggled aboard a steamer headed for Boston. Now she was warning of another massacre in Ireland by the English.

Meanwhile, money had begun to flow from Boston to Dublin. In June, the Irish Relief Fund raised $2,330 in one night, with Mayor Curley kicking in $100, at Boston Symphony Hall. In July, the National Volunteers of Ireland held a fundraiser in Roxbury. A letter was read from Eoin MacNeill, chairman of the provisional committee in Dublin, stating that “arms were badly needed, and asking the Irish here to do their best to meet the want.” Also in July, Friends of Irish Freedom leader Joseph Smith of Lowell traveled to Ireland with $100,000 raised for the benefit of widows and orphans. He was detained in Liverpool and prevented from entering Ireland.

By August, the Irish Relief Fund had raised over 100,000 pounds, “a sum greater than that which Parnell collected in 1879 – 80 for the Irish famine,” noted the Republic. Rather than pacifying the Irish Diaspora, the actions of the English instead revitalized it.

Almost a year after the Irish Rising, the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, and Boston’s focus quickly shifted to the war effort. Finally, here was something all Boston Irish could agree upon: “We are Irish Americans, but Americans first and last.”

David I. Walsh, elected as the first Catholic Governor of Massachusetts in 1914, put it best when he said, “Let every man of Irish blood face his duty as an American citizen in passing judgment on national and international questions. Let us remember to be Americans first.”

That perspective lasted throughout the war, and when WWI officially ended on November 11, 1918, the Boston Irish turned their attention back to Ireland. The war to end all wars had vowed to “protect the rights and liberties of small nations,” and the Boston Irish wanted to make sure that promise was kept. ♦

_______________

Michael Quinlin is author of Irish Boston (Globe Pequot Press: 2013) and editor of Tales from the Emerald Isle and Other Green Shores (Lyons Press: 2014). He co-founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association in 2000 and created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail. Mike lives in Milton, Massachusetts with his wife Colette and son Devin.

Thanks for a very informative article about the day to day American (Boston) response to the struggles in Ireland in 1916.

The author’s original text of this article was erroneously edited to refer to “this Brendan Behan verse.” That passage has been removed from the story, with our apologies.