Unheralded men and women became leaders in the crucible of 1916. A new book by the Royal Irish Academy offers portraits and biographies of those involved in the Rising.

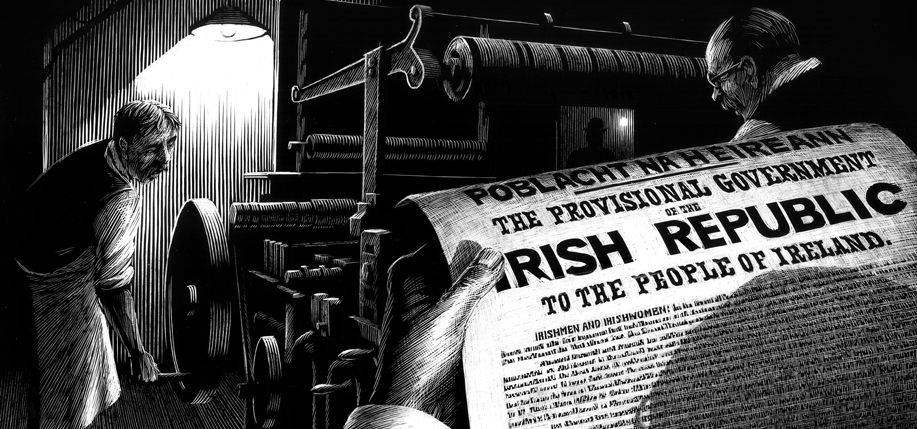

Irish people are raised on stories of 1916. We’re told of Pádraig Pearse reading the Proclamation of the Republic from the steps of Dublin’s G.P.O., James Connolly facing a firing squad strapped to a chair, and Joseph Plunkett marrying his sweetheart hours before his execution.

A new book from the Royal Irish Society offers us a fresh perspective. 1916: Portraits and Lives features the biographies of 42 people who were involved in the Rising. They include the leaders, those who were executed, four who were killed in action, one who was murdered, nine women, three nationalists who opposed the Rising, and six members of the British administration.

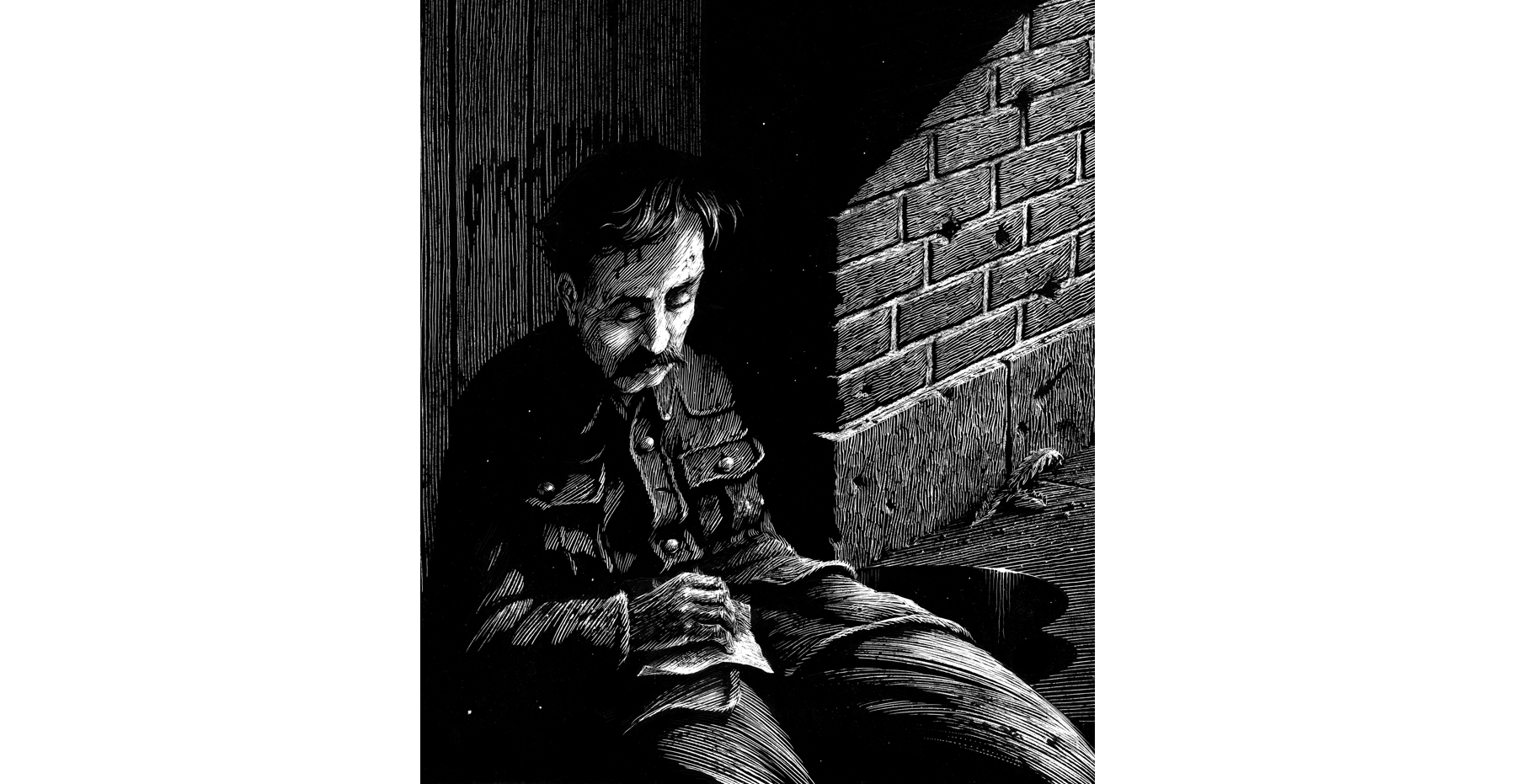

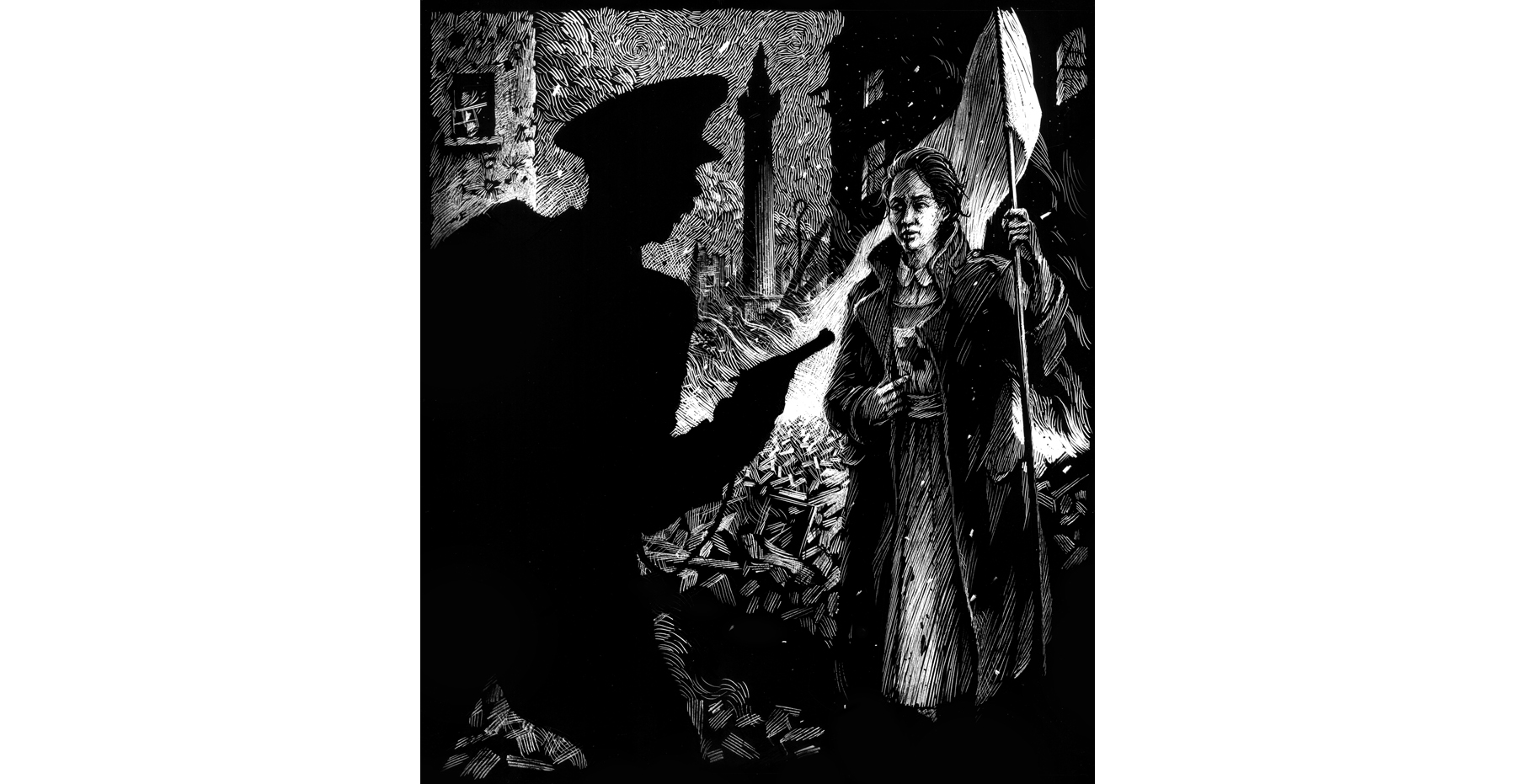

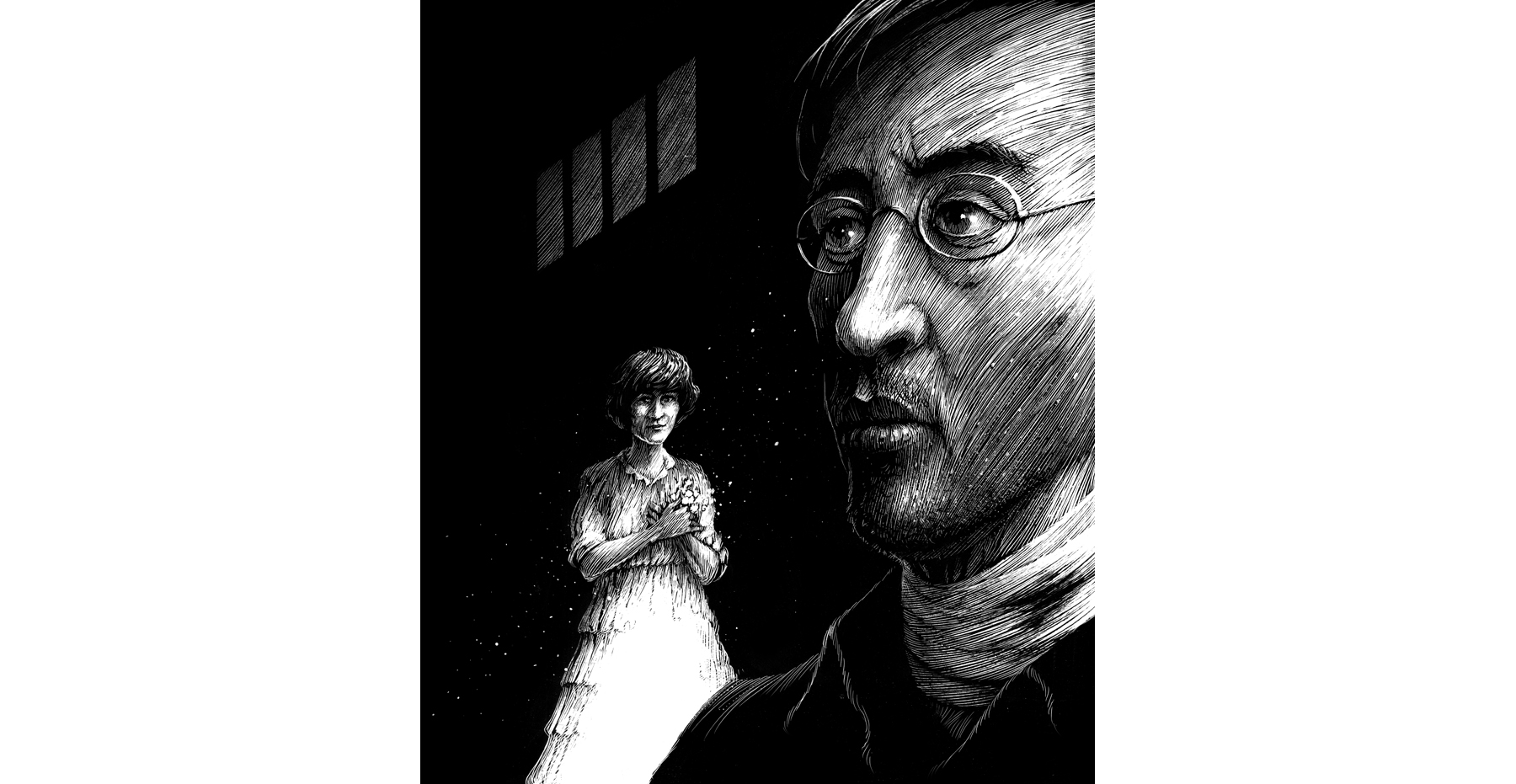

Written by eminent historians Lawrence William White and James Quinn, with superb black and white drawings by David Rooney, the book brings the Ireland of 1916 to life and introduces many surprising new facts.

The first portrait is of Augustine Birrell, Chief Secretary of Ireland at the time. His surprise is that far from representing the tyranny of British rule, he supported Home Rule for Ireland.

Roger Casement comes across as volatile; so much so that the editor, who discusses him in this book, suspects he had bipolar disorder.

The biography of Éamonn Ceannt notes that his brother William fought with the British Army in France while Éamonn fought against them in Ireland. Such divided loyalties in one family show how complicated the country was in 1916.

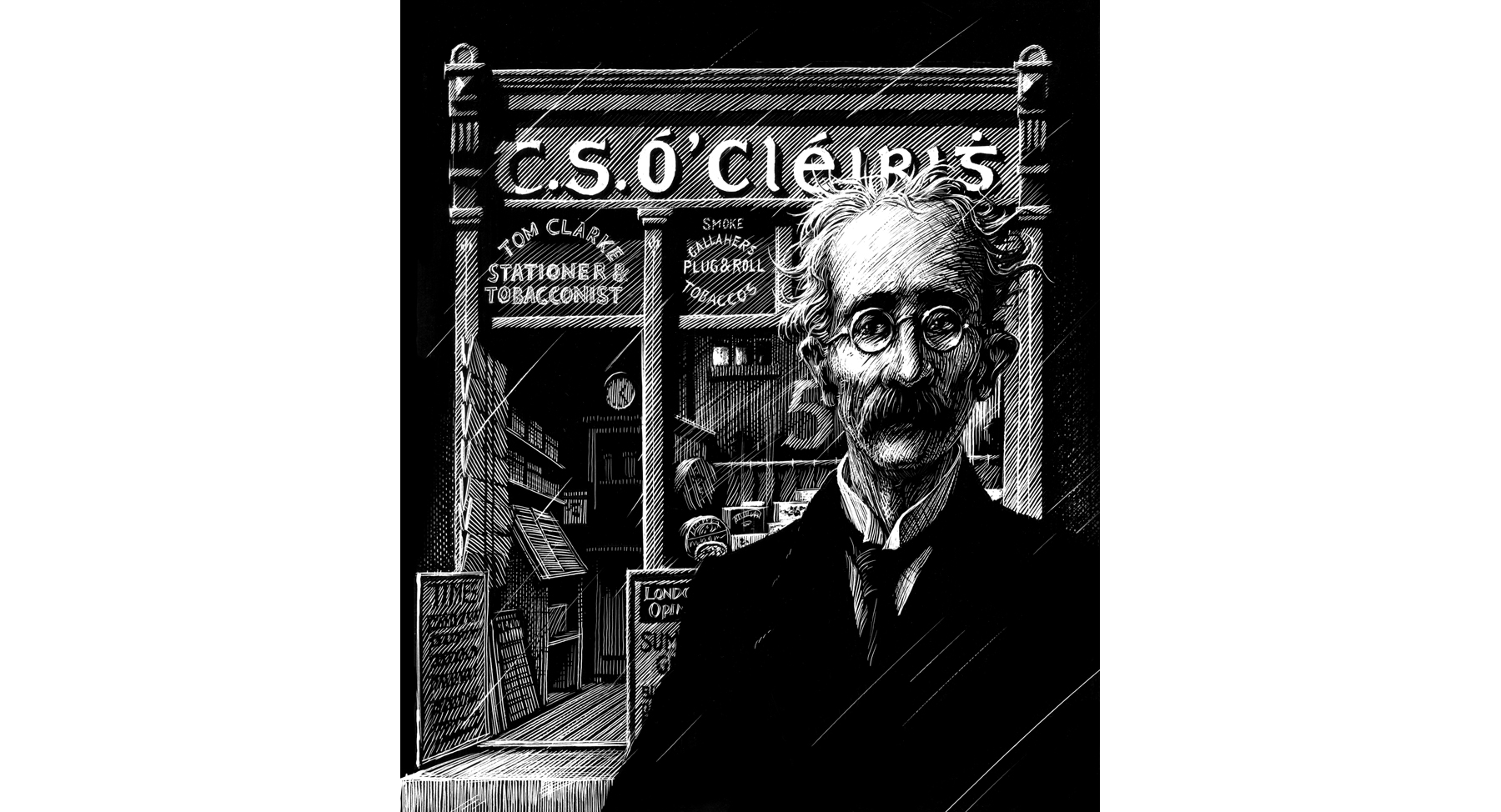

Tom Clarke was the man who linked the rebels of 1916 to the Fenians of old. Released from prison after serving time for a bombing campaign in England, he set up a newsagent’s shop in Dublin as a front for his activity in revitalizing the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B.). He inspired the younger rebels to violent revolution.

“During the Rising, those who observed him commented on how happy he looked; the insurrection being for him the culmination of a decade’s work and a life’s ambition,” writes his biographer, James Quinn.

Bulmer Hobson was on the wrong side of history. A committed nationalist, he was involved in everything from the G.A.A. to the I.R.B. but he wasn’t an extremist. As a result, he wasn’t party to plans for the Rising until it was imminent. Because he thought the rebellion was hopeless, he did his best to prevent it from happening. He was punished for this by being excluded from Irish politics forever after, barred from political meetings and ostracized by former friends.

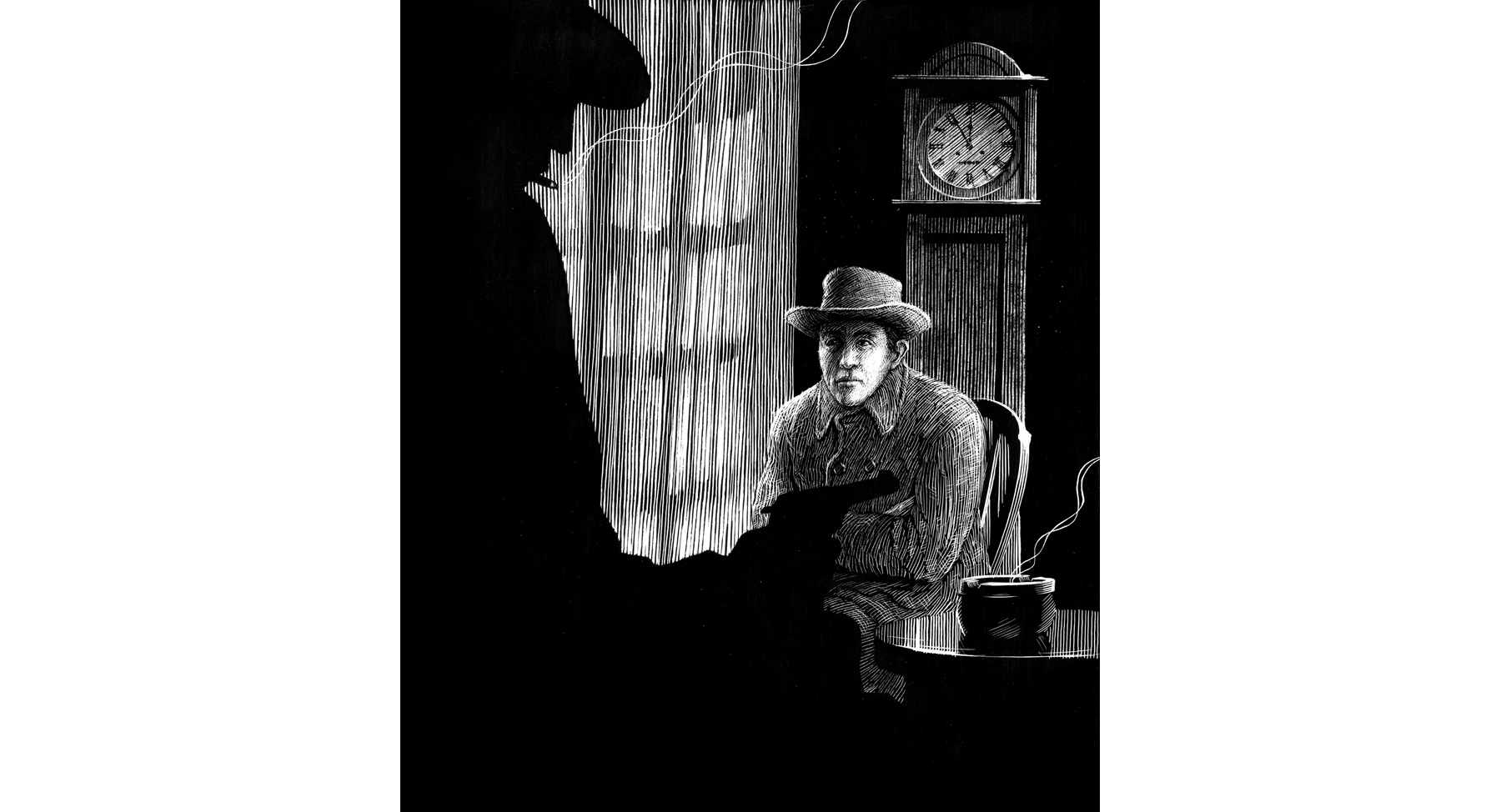

Michael J. O’Rahilly was another activist who opposed the Rising. He was involved with the Irish Volunteers from the start and pushed for rebellion at the outbreak of WWI. He tried to contact Germany to get support but, when this failed, he sided with Hobson, backing a defensive strategy, rather than a pre-emptive rising.

When he saw the Rising taking place on Easter Monday, he felt he had a moral duty to stand with men he had trained. He said, “I helped wind up the clock so I might as well hear it strike.”

He fought in the G.P.O. and was wounded charging a barricade on Moore Street. He bled to death in a laneway.

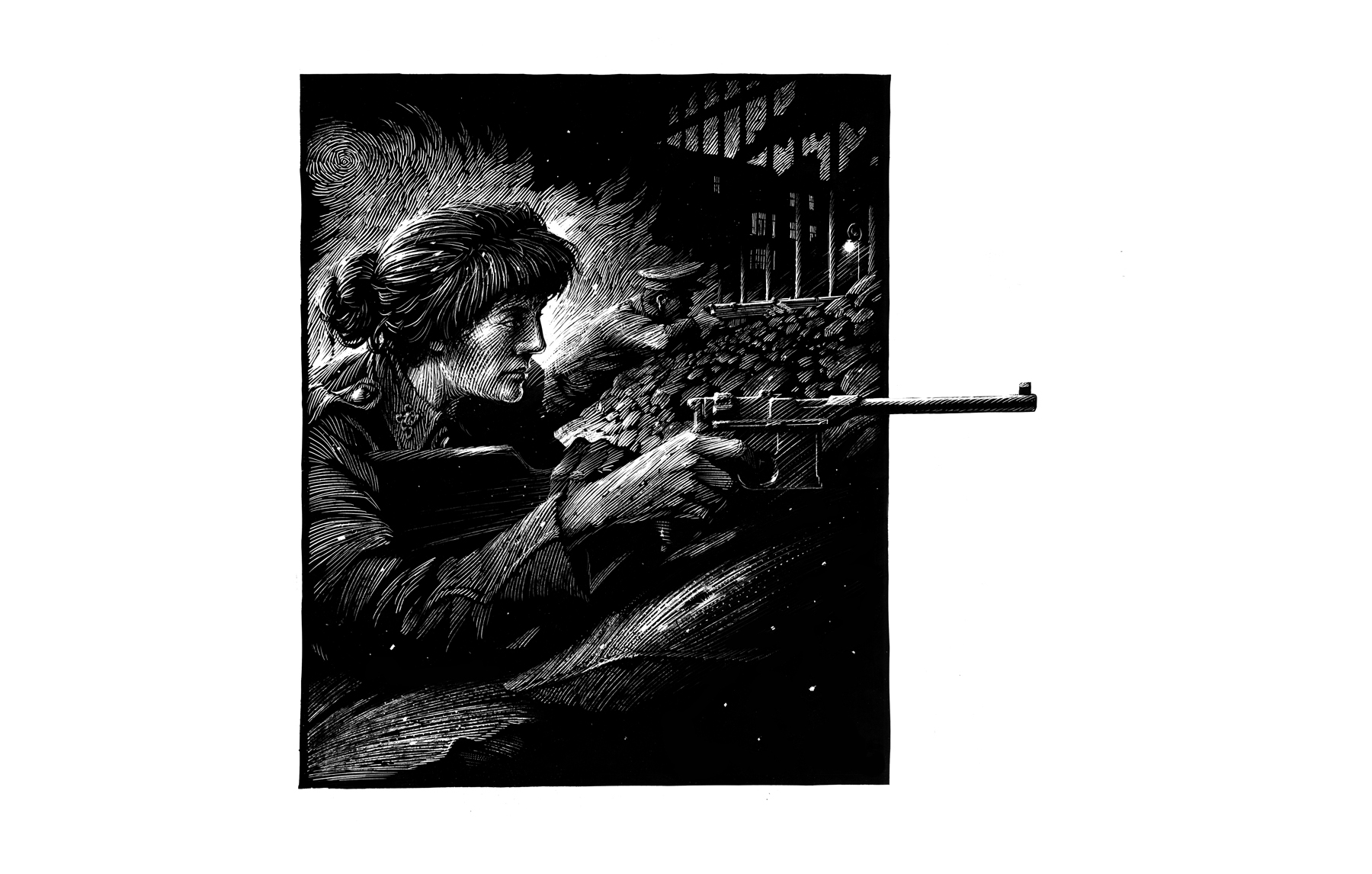

Constance Markievicz is perhaps the most glamorous of the rebels. She was born into an aristocratic family, but her interests weren’t those of a typical young lady. She campaigned for women’s suffrage, organized soup kitchens in Dublin’s slums, and believed in the need for armed rebellion against British rule in Ireland.

Constance’s role in the action – second-in-command in St. Stephen’s Green – meant she was initially sentenced to death. Her sentence was commuted because she was a woman.

Her life after prison was erratic. She spent the War of Independence on the run and took the anti-treaty side in the civil war. She won a seat as a Fianna Fáil candidate in the 1927 election, but her hard life meant her health failed her. She died a pauper in hospital later that year.

The fates of Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan are less disheartening. Childhood friends, they did everything together. They served under James Connolly in the G.P.O., performed courier duties all over the city, and delivered ammunition by hiding it under their skirts.

Pearse chose Elizabeth to discuss the terms of surrender with the British on April 29th, fearing that a man given this task would be shot. Elizabeth approached the barricades waving a white flag and was taken to Brigadier Lowe. Later that day, she accompanied Pearse when he surrender to Lowe in person, and can be glimpsed in press photos taken of the occasion.

Elizabeth and Julia lived together after the Rising and remained active in nationalist politics.

John Maxwell was the British officer who restored order in Dublin. He had been recalled from Egypt shortly before the Rising broke out and his availability appears to have been the main reason he was selected for the task.

“That he – a mid-ranking general of no great reputation, was selected to go to Dublin reflects how comparatively low down Ireland was in the scale of British political priorities in 1916,” writes his biographer, Keith Jeffery.

Because of the book’s alphabetical order, 231 pages go by before we arrive at Pádraig Pearse, the pre-eminent figure of the Rising. His biographer in this book, J.J. Lee, counters the idea of Pearse exalting sacrificial bloodshed. He believes Pearse hoped for success, not failure.

“It’s easy to forget that neither Pearse nor anyone else planned the actual rising that occurred,” says J.J. Lee. “It was the rising no one planned.”

The Rising was supposed to take place nationwide on Easter Sunday, and with ten times as many Volunteers as turned out on the day.

The next biography is that of William Pearse. He was devoted to his older brother Pádraig and followed him in everything he did. This included fighting in the G.P.O. on Easter Monday.

William played a minor role in the Rising and when he was executed in its aftermath, there was a huge public outcry. His death discredited the executions in the eyes of many moderates.

Joseph Mary Plunkett was a sickly man but a military mastermind. His initial plan was for a rising in Dublin and the west, coordinated with a German invasion up the Shannon. When this was rejected by the Germans, it was he who came up with the strategy of occupying key city center buildings instead.

John Redmond merits a long entry in this book. He became an M.P. for the Irish Parliamentary Party at the age of 24 and dedicated his life to winning Home Rule for Ireland.

He almost succeeded when the third Home Rule bill was passed in 1912. The bill was expected to become law in the summer of 1914, and Redmond hoped to have won the Ulster Unionists over to the idea by that time.

His hopes were dashed when the Ulster Volunteers were formed in 1912 and the Irish Volunteers in 1913. Both groups began to import arms and civil war might have erupted were it not for the outbreak of WWI.

Redmond was caught entirely unawares by the Rising and saw it as an assault on all he stood for. He died following an operation for gallstones in March 1918. His party died a political death soon afterwards when Sinn Féin won 73 seats to their six in the general election.

Men, women, moderates, extremists, socialists, feminists, and many more are given voice in this insightful book. It’s a beautiful book too, with black and white illustrations of each profiled individual by the artist David Rooney.

By telling the stories of 42 remarkable people associated with 1916, this book expands on all those stories we’ve been told in the past. It adds to our understanding of the Ireland of 100 years ago and of those who played a part in the rising that eventually led to its independence.

_______________

1916: PORTRAITS AND LIVES

Edited by James Quinn and Lawrence William White and illustrated by David Rooney.

It retails for €30 and is available for purchase here: https://www.ria.ie/1916-portraits-and-lives

Leave a Reply