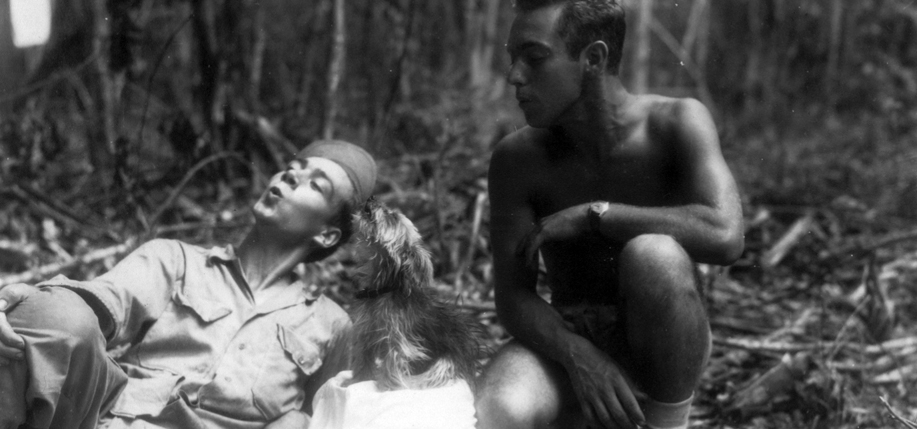

The famous war dog who served in World War II, and Bill Wynne, the U.S. Army Air Force G.I. who adopted her.

The first time Cpl. William Wynne saw Smoky, he found it hard to believe she was a dog. “She was as big as my G.I. shoe,” Wynne says. “She weighed all of about four pounds.”

In addition, the animal was almost bald; someone had hacked off most of her fur in an attempt to make her comfortable in the tropical heat.

It was March 1944. The day before, Pvt. Ed Downey’s jeep had stalled in the New Guinea jungle near the 5th Air Force’s primitive encampment. As he tinkered with the engine, Downey heard an animal whimper. The G.I. investigated and discovered a scrawny little dog struggling to jump out of a foxhole. Downey brought her back to camp but said nothing to Wynne, his tent mate, and an avowed animal lover. Downey insisted he wouldn’t share quarters with “a mutt.”

Instead, he gave Smoky to another buddy.

The petite pooch was destined to be Wynne’s dog, however. The following day, her temporary owner needed cash for a poker game. He sold Smoky to Wynne for two pounds Australian, then worth $6.44 U.S. More than 70 years later, Bill Wynne considers this the bargain of a lifetime.

Named for her coloring, the little blue-gray dog had luck to spare, beginning with her fortuitous rescue by Downey. Fortune smiled on her again when Wynne became her master. He immediately took her to the Quartermaster Corps veterinarian for rabies vaccinations. Fearful that Smoky would contract scrub typhus, a virulent tick-borne disease that killed dogs and sometimes humans, Wynne daily bathed her in his helmet. He fed Smoky army chow and gave her chlorinated water. During air raids, he raced with his pet to shelters where he covered her sensitive ears with his hands to muffle the booms of exploding bombs.

Smoky delighted in chasing enormous exotic butterflies around the jungle, a pastime Wynne permitted while watching out for pythons that would prey on her. One day she slipped too far into the jungle and her frantic master enlisted the help of natives to retrieve her.

Smoky distracted Wynne from boredom, stress, and homesickness. His forebears had come to the States from County Waterford and County Mayo and settled in Pennsylvania, but Wynne spent most of his childhood in Cleveland, Ohio. Shortly before shipping overseas, he proposed to his longtime sweetheart, Margie Roberts, and then carved their initials on the trunk of a beech in Cleveland’s Metroparks. Earlier, Margie had given him a mongrel puppy, Toby. When he took Toby to obedience school, Wynne discovered his own talent for dog training.

Now Toby lived with Wynne’s mother. Thousands of miles away, the 22-year-old corporal taught Smoky tricks whenever he was off duty. She quickly mastered simple commands and then learned to play dead, jump through hoops, climb a ladder, cross a tightrope blindfolded, ride a scooter, and “walk” a barrel. By omitting an “e” from her name, Wynne shortened it, making it easier for Smoky to spell. She did this by choosing scrambled cardboard letters in the proper order.

Smoky even “jitterbugged” with her master, lifting a front paw four times, and then spinning around as he did the same. Accompanied by his harmonica, she “sang” for two-minute stretches.

Wynne gradually acquired props for Smoky’s routine such as a scooter, a sliding board, a tightrope, and a ladder. She even wore a costume – a clown suit sewn from a salvaged parachute.

Wynne’s “day job” consisted of working in the photo lab. He also photographed accident sites on search-and-rescue missions for downed airmen.

Hazards included sudden, violent storms, flying extensive distances over water, and the threat of crashing in the jungle.

After his first mission, Wynne’s friends gathered in his tent to hear about it.

Wynne recalls that one of them asked, “Hey, Wynne, if you get knocked off, can I have Smoky?”

Immediately other men protested. They squabbled over who would be responsible for Smoky if Wynne’s plane didn’t return. He interrupted them.

“I said, ‘The hell with you guys! I’ll take the dog with me. She’s going to be good luck!’

“And she was.”

Snug in her master’s canvas musette bag, Smoky slept through 12 combat missions hanging from the ceiling of an inadequately armed Catalina PBY5a.

Meanwhile, Wynne speculated about Smoky’s unlikely appearance in the New Guinea jungle. Guessing that retreating Japanese forces had abandoned the dog, he asked an interpreter to talk to her. Smoky ignored every command in Japanese, however.

Wynne also puzzled over his pet’s breed. He had never seen a creature like her. Squadron members solved the mystery when they spotted a National Geographic photo of a show-quality Yorkshire terrier, a “Yorkie.” It was a dead ringer for Smoky.

Wynne was assigned to the 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron. When its men chose Smoky as their mascot, Wynne snapped a photo of her peering out of his helmet and entered Yank magazine’s mascot contest.

Months passed before he learned that Smoky had won “Best Mascot” for the South West Pacific Area. By then, Wynne was recuperating from dengue fever in the 233rd Station Hospital. Wynne’s buddies brought his pet to visit him, and they delivered his mail, which included the issue of Yank with Smoky’s winning photo.

Smoky’s triumph created a sensation. Even reformed dog-hater Ed Downey, then serving in a different outfit, made a special trip to see the Yorkie he’d rescued. Nurses took Smoky on rounds so she could cheer up soldiers wounded on Biak and Wakde Islands. She worked as a therapy dog by day and slept on her master’s cot at night.

Upon Wynne’s discharge from the hospital, Smoky accompanied him on a two-week recuperative leave to Brisbane. At the invitation of the Red Cross, she showcased her repertoire of tricks for sailors and Marines at the 109th Fleet Naval Hospital and soldiers at the 42nd General Army Hospital. Fans in wheelchairs ferried her from ward to ward.

Smoky’s luck held when she and Wynne returned to the combat zone. In January 1945, kamikazes attacked their convoy as the 26th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron headed for the Philippines. A shell from a nearby American destroyer struck their vessel mere feet from where they huddled, wounding eight men. Neither Wynne nor Smoky was harmed, however.

When the squadron set up in Lingayen, about 80 miles northwest of Manila, the mite of a dog was a mighty big help to men of the communications section. They asked Wynne if she would pull a telephone line through a 70-foot-long culvert under the airfield. If she completed the task, Smoky would spare her two-legged buddies from exposure to strafing by enemy aircraft as they spent days digging a trench in the runway, laying wire and replacing the airstrip.

Although worried that snakes or rats might lurk in the pipe, Wynne agreed.

To his relief, Smoky finished the job in just a few minutes. The feat earned her a steak and official “war dog” status.

Meanwhile, Smoky’s reputation as an entertainer traveled with the squadron. In Manila, the Red Cross asked Wynne to do a show at the 120th General Army Hospital. War-weary troops also laughed at Smoky’s antics in a recreation hall on Okinawa. Japan surrendered while Wynne was stationed on Okinawa, but new dangers arrived with typhoon season. His tent vanished as soon as the first storm struck, and so he clutched Smoky, braced himself against the wind and inched his way to the mess hall. Rain drenched that flimsy building for days, however. Desperate to escape the relentless downpour, Wynne and his little dog took shelter in a burial cave.

The squadron relocated to Korea not long after, and then received orders back to the States. Military regulations banned animals from homeward-bound ships, but Wynne would not abandon Smoky. He hid her in his oxygen mask’s carrying case and smuggled her aboard the U.S.S. William H. Gordon. Sympathetic sailors stashed larger dogs in a safe compartment. Despite threats from the commander, all the canine stowaways eventually received permission to enter the United States.

With discharge papers in hand, Wynne arrived in Cleveland in November 1945. Smoky smoothly transitioned to civilian life but continued to entertain G.I.s from time to time. At a veterans hospital, an incoherent soldier abruptly reached for the dog. Wynne interrupted the act to hand him the Yorkie. The man smiled and rocked the little bundle. Weeping nurses informed Wynne that this catatonic patient had not responded to his environment in two years – until his encounter with Smoky.

In 1946 Wynne and Margie married. Wynne dreamed of training dogs for movies, and so the newlyweds struck out for Hollywood with Smoky in tow. When she demonstrated her tricks, Wynne quickly landed a job as an assistant dog handler. He worked with dogs appearing in movies with Fred MacMurray, Ronald Reagan, and Claudette Colbert. Despite his grueling schedule, Wynne’s wages barely made ends meet. Margie soon suffered from homesickness, and it turned out, from morning sickness, too. Choosing his family’s needs over a career in show business, Wynne returned to Cleveland and worked as a flight photographer for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (later NASA).

He and Smoky moonlighted, performing at county fairs and orphanages, nightclubs and nursing homes. As Mr. Pokie and his dog Smoky, they entertained children on a Cleveland TV show. They also brought dog-training sessions to live television.

Smoky retired from show biz in 1954. Despite a few health problems, she remained alert and active until February 1957, when she died during an afternoon nap at the age of 14. The family broke a park rule and buried their tiny terrier under the tree on which Wynne had carved his initials and Margie’s 17 years earlier.

Cleveland recognized Smoky as a local celebrity and a daily newspaper printed her obituary. When former Army nurse Grace Guderian Heidenreich read it, she contacted Wynne to relate her own wartime mystery. In December 1943, when she was Lt. Guderian and stationed in Australia, she received a Yorkshire terrier puppy as a Christmas gift from her future husband. Capt. Heidenreich had purchased the dog in Australia. When Lt. Guderian’s hospital unit was transferred to New Guinea, the Yorkie went with her. Unfortunately, the nurse took her pet to a U.S.O. show, where the terrier wandered off.

Since personnel from all New Guinea bases attended that show, someone may have found the dog and brought her to Nadzab, where she got lost in the jungle. Given that few purebred Yorkshire terriers were registered anywhere during the war years, Wynne believes that Smoky must have been Lt. Guderian’s pet.

Lt. Guderian married Capt. Heidenreich, a Clevelander, and settled in his hometown after the war. Smoky’s original owner had lived just blocks away from the Wynnes for most of the little dog’s life.

Smoky’s fame continues to grow decades after her death. Now 93 years old, Wynne currently seeks a producer for the screenplay based on his memoir, Yorkie Doodle Dandy.

The cable program “Animal Planet” devoted two episodes to Smoky and she has appeared in more than 50 books. In recent years, the Imperial War Museum in London and the National World War II Museum in New Orleans featured her in special exhibits about animals in wartime.

Memorials to Smoky have sprung up throughout the United States and Australia. She represents all war dogs in a monument in Cleveland’s Metroparks, dedicated on Veterans Day, 2005. Based on Yank magazine’s winning mascot photo, a bronze statue shows the grinning Yorkshire terrier nestled in her master’s helmet.

During her life, Smoky served as a therapy dog, a war dog, an entertainer, and a first-class morale booster. All these roles resulted from her chance discovery by a G.I. in the New Guinea jungle. One of her greatest tributes is a living legacy – each year Yorkshire Terrier National Rescue recognizes extraordinary cases of abandoned Yorkies who found loving adoptive homes.

It’s called The Smoky Award. ♦

_______________

A freelance writer in Brecksville, Ohio, Jerri Donohue’s work has appeared in regional, history, and religious publications. Jerri’s favorite subjects always relate to World War II and in this issue, she writes about Smoky, the lucky WWII Yorkie.

Photos used by permission Smoky War Dog, LLC/Wm. A. Wynne, copyright 2013.

Thanks, Jerri for the wonderful article – very well done, and a true honor given to both the dog and the man! Bill Wynne will be speaking at the Rocky River Library Auditorium at 3:30pm Friday, December 11th. A brief award ceremony will follow with a presentation of the Purple Cross Award from the Australia RSPCA – the highest Australian honor given to animals who have saved lives. See also the December issue of Smart Business and today’s Cleveland.com (search ‘Smoky’)! The screenplay is moving forward as well! A wonderful Holiday season to all!

Wow, Ms. Jerri Donohue and Irish-America, congrats on this superbly-written story. Wish I could do so well. (See my “Is Oscar Irish?” in May issue.)

All the best. Ms. D, please put me on your emailing list if you have one.

Good job! Wow.

Tagus dut (Thanks) and bravo to Ms. Patricia Harty for carrying this story and the one on Katie, the White House cool. l love history.

“The world is not built of molecules; it is built of stories.”

Happy New Year, from Peter Garland and Family

I came across the book and was terribly excited, as my husband is a WW 2 buff and devoted to his Yorkie, Wilberforce. I purchased several copies, and was writing to my son at Basic Training, had ran out of topics a d did a book report on this little gal. Stampin Up did a series of stamps and has a Yorkie in a boot, I believe fashioned after Smoky. I stamped it on the page. How amazing that she is still inspiring and entertaining Soldiers (albeit via my letter to my Irish boy!)

Enjoy another story about Smoky on Blackpool Records here: https://youtu.be/YdhWQGHe2K0

.. and from CNN’s GreatBigStory.com:

https://youtu.be/Om4hxolzkdk

Have it ready to go when my husband gets home. Thank you SO much!