From County Down to downtown Manhattan, Jim Clerkin has moved around, and systematically up, in the world. After a career in the alcoholic beverage industry, he’s landed the top position in Moët Hennessy in North America. Now that he’s there, his goal is to help others do the same.

Jim Clerkin has had a relationship with Hennessy since before he was born. His father’s drink was cognac and ginger ale. His brand – Hennessy. Clerkin remembers serving his father while working part-time at a friend’s bar in Rostrevor, where he grew up. It probably wasn’t the most unlikely of drinks, given that Hennessy was the first cognac to be imported to Ireland in the 19th century. But of all the kids in County Down whose fathers or mothers drank the same mix, Clerkin is the only one to head a division of the brand.

He now serves as the president and CEO for Moët Hennessy North America, working with several wholesalers across Mexico, Canada, and the U.S., and managing 13 of the world’s most famous brands of spirits and wine, including Dom Pérignon, Moët & Chandon, Veuve Clicquot, Glenmorangie and Ardbeg scotches, Belvedere vodka, and, of course, Hennessy.

It’s a role he’s held for only a month, but that’s a technicality. In 2008, Clerkin was appointed chief operating officer for Moët Hennessy U.S.A., and in October 2010 he was promoted to president and CEO. Now, his responsibility has been extended to Canada and Mexico, creating the North America division. It is a telling promotion, and, consequently, he is now the longest-serving CEO in the industry in the U.S. – for good reason.

Charlie Marinoff, chairman and CEO of the Charmer Sunbelt Group, one of Moët Hennessy’s primary distributors, calls Clerkin a “remarkable leader with a talent for building brands and creating brand value,” and Moët Hennessy’s VP of Legal, Chris O’Rourke, cites his “tremendous energy and passion” as key to the company’s recent growth.

On one hand, it’s a job Clerkin has been groomed for his entire professional life. He began working for Guinness in Northern Ireland in 1976, spending 18 years with the company and rising in the ranks until becoming sales director and joining the board at 36. He then spent five years as managing director of Gilbey’s of Ireland and subsequently served as president of Diageo’s North American Western Division, president of Allied Domecq U.S.A., and senior vice president and president of North America for Beam Global Spirits. It is the trajectory of a businessman, and it’s not hard to see how Clerkin ended up here, with roles of increasing responsibility and more geographic autonomy. He’s been a stalwart figure in the alcoholic beverage industry for nearly 40 years.

On the other hand, it might just as easily never have happened. His entrée to the industry was born of unlikely happenstance in the Rostrevor pub where he served his father Hennessy and ginger ale. He had graduated from both Newry Technical College and Lisburn Technical College and was two years into a job as a time and motion study engineer, which he already knew was not for him.

A sales manager from Guinness came into the bar with co-workers and, in Clerkin’s words, “because I didn’t own the bar, I managed to tell them a few things about what I thought of their company and the way they were servicing us.” Instead of taking offense, the manager, who was actually head of sales, offered him an interview. That man, John Lavery, who became Guinness’s managing director and would be Clerkin’s mentor for the remainder of his time at Guinness.

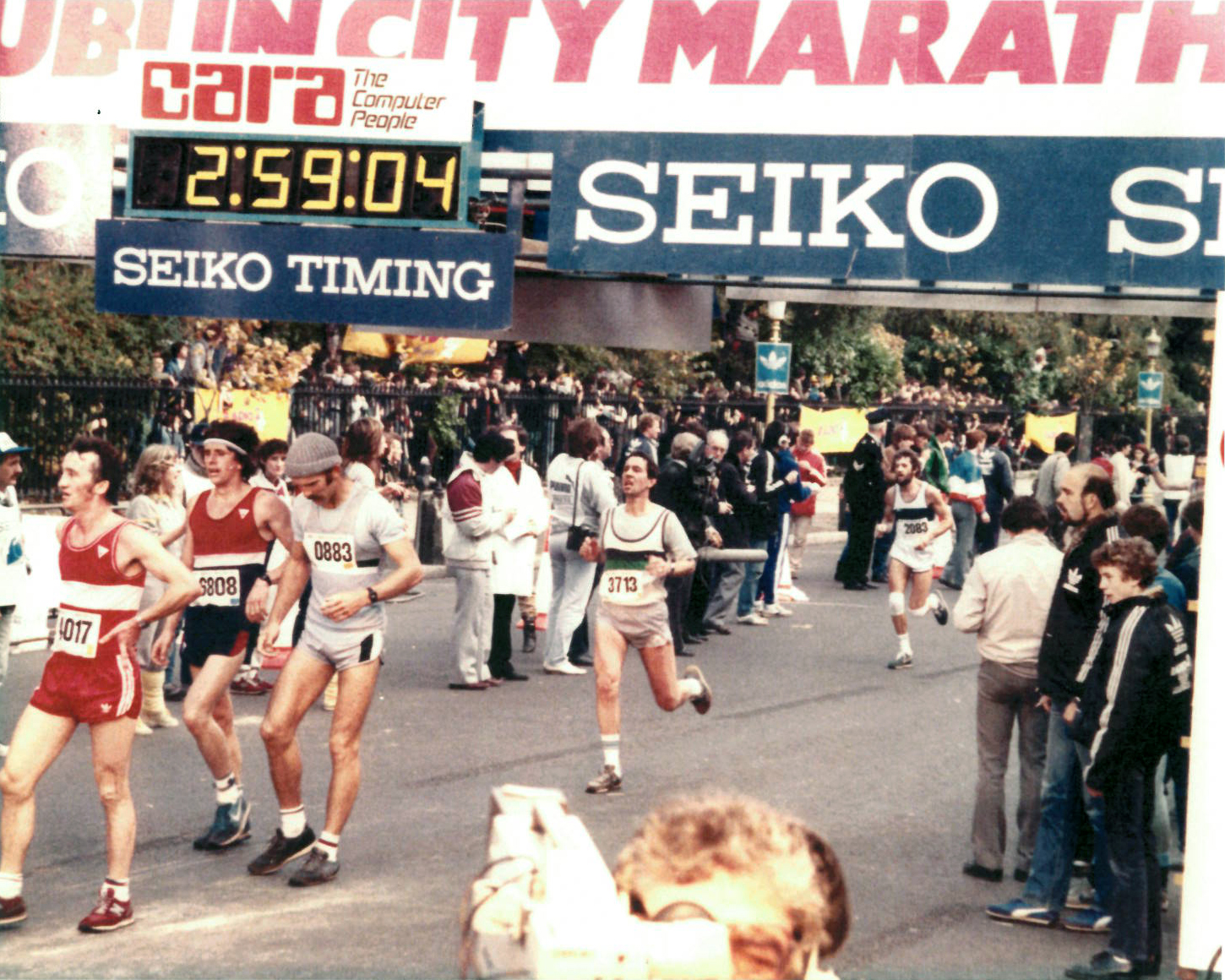

Coincidental as it was, it shouldn’t be surprising that Clerkin negotiated his way into the industry with determination. He’s also run four marathons, on a bet.

“A gentleman from my hometown many years ago who claimed that squash – which I played at a competitive level – that squash players weren’t real athletes; we just ran little sprints. He said, ‘Real men run marathons,’” Clerkin recalls.

His first time wasn’t good enough for his friend, so the bet escalated, as they do, until Clerkin could run a sub-three-hour time. He did in 1983, coincidentally the same year that Maurice Hennessy, of the Hennessy Hennessys, ran the marathon, though Clerkin didn’t know it at the time.

At 61, he is still fit, though these days he prefers golf to marathons and can shoot in the low to mid 80s. He is handsome in the way that men from the rural North tend to be, which is to say that his skin betrays a childhood spent outdoors working on the land. He is toned, but not tan; his hair is neat, but not overly combed; he is as easily pictured in coveralls as he is in a tailored suit. You can see it in his eyes when he poses for photographs – a self-serious mode of looking that says, “There’s work to be done.”

Clerkin is the oldest of nine siblings, eight boys and one girl, and grew up on a small farm in the foothills of the Mourne Mountains, outside of Rostrevor, where most of his siblings still live.

“I guess we were close to being poor, but it never felt like that,” he says. “While it seemed completely organic and natural, it’s only now that I realize we were living off the farm, so we had our own potatoes, our own vegetables, our own lettuce, our own carrots, our own animals.

“And while there wasn’t a great deal of money, there was a fantastic amount of love and affection within a big family,” he says, echoing one of his mother’s phrases he remembers her saying of her own childhood – we weren’t rich, but we were rich in love.

This care would prove important to Clerkin’s professional growth. His father was the one who encouraged him not to turn down the Guinness offer. Clerkin calls him his “best friend” and his first role model.

“You know people talk about hard work, but if you have a farm, you are on call 365 days a year and there are no holidays because of the animals. I spent a lot of time with him, working with him, going to the markets with him. We were like buddies,” he says.

“I never felt, ever, that there was a subject that I couldn’t talk to him about. And not only was he my dad, he was a great leader, he was a great people person, he was a great motivator. A lot of people would come to my father for advice, and he was extremely well known in our village. He was known as someone who could fix things, who could get problems sorted.”

The same can be, and is, said of Clerkin.

“He reminds me of the Sean Thornton character in A Quiet Man,” says Wayne Chaplin, president and CEO of Southern Wine & Spirits, who has worked with Clerkin for over a decade. “He is thoughtful and introspective yet forceful and strong willed when the situation demands.”

Peter Sheridan, CEO of Co-operation Ireland, speaking of Clerkin’s dual roles heading both Moët Hennessy North America and as chair of the U.S. Board of Co-operation Ireland, says “I am often convinced Jim can divide himself in two.”

“It would be easy for him to say ‘I am too busy,’ but that’s not in his vocabulary.” he says. “He is thoroughly determined that young people coming out of the conflict in Northern Ireland will not have to experience the tragedies he did as a boy during the Troubles. His compassion and drive mean many young people in the North will have a brighter future.”

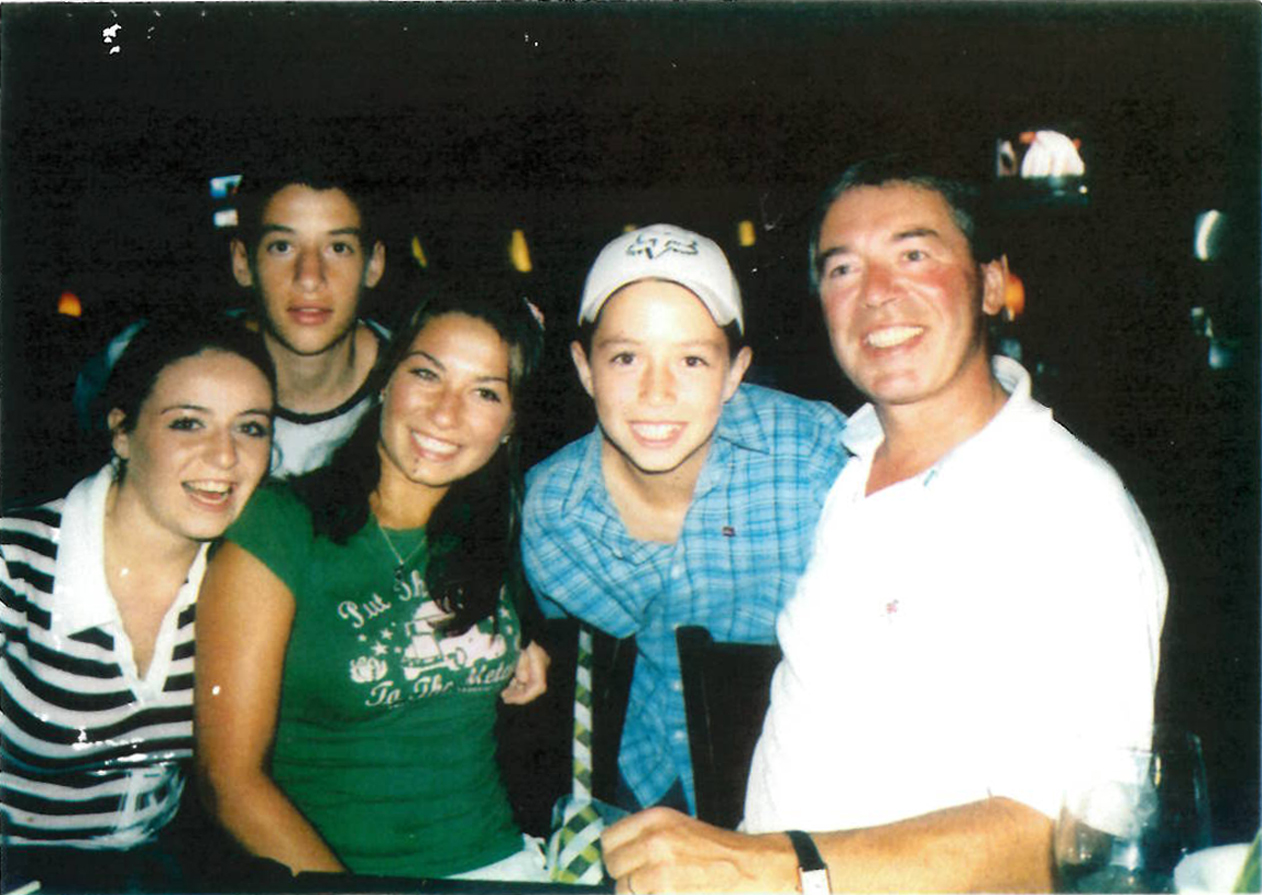

Now, Clerkin is the father of four grown children – James, Jennifer, Rachel, and Luke – is about to become a grandfather, and lives a long way from a farm. When we meet in Moët Hennessy’s offices in lower Manhattan, he’s talking about run-ins with Clint Eastwood and Bono at the Moët Hennessy Golden Globes after party, attending the premiere of the new James Bond movie in Mexico City the day before, and the noise of living in Manhattan that he still struggles to get used to, before the formal interview even starts.

When we begin, he eases into the corner of a couch in his office, assuming the posture of a man confident in his surroundings, and looking like a man who could be comfortable almost anywhere. It is the posture of someone happy to tell stories, and he does. The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Did you have a dream job growing up?

When I was attending Newry Technical College, a good friend of mine, Jeffrey Prince from Warrenpoint, and I always had a dream of becoming helicopter pilots in the Royal Navy. We had a dream of getting the best possible training, and then after training and graduation we would become professional pilots – commercial pilots looking after fires and spraying crops. But it ended up being what it was, nothing but a dream.

How do you think you have changed since growing up in a rural environment to now?

I think it’s been an evolution, not a revolution. When I started playing squash, I wanted to become the club champion and it took many years before that happened. When I started running I wanted to run a marathon and that took many years. And when I ran a marathon I wanted to run it in under three hours, and that took many years. When I took up golf I wanted to break 80, and that took years. In other words, I seem to be someone who when I get to my objective I’m not necessarily happy to stay there, I like to try and see how far I can go.

But in the more recent times, it’s no longer about what can I achieve; it’s more about what I can get others to achieve. Up until I became the managing director of Gilbey’s, I guess I could be described as being very ambitious. And once I became the managing director, it became obvious to me that if I really wanted to progress, I had to think more about others and surround myself with good people, try and get them into the right jobs. And I’ve also discovered that you can get good people, but if you put them in the wrong job, everybody ends up in tears. Particularly in the last ten years, any success I have had has been built upon the efforts of getting great teams together.

Are there qualities you think have stayed the same?

I think the strongest quality that I hear given back to me from competitors or customers or wholesalers, which I really appreciate, is that “he’s a straight-talking guy.” It’s not that I’m direct at all, but I really like to try and get the issues on the table as quickly as I can. Not in any way to become confrontational, because I don’t like confrontation – I’m not afraid of it, but I don’t particularly like it. The key to getting something on the table relatively early is to try to either find a solution or quickly figure out where the differences are, so instead of wasting a lot of time on areas that we clearly agree on, lets challenge the area where there’s a difference and set about resolving it.

Do you find yourself doing that in your personal life, too?

I think if I have a weakness, and I’m sure I have many, one of them that’s pointed out by my children is that occasionally I fall into the trap of trying to communicate and react with my family a bit like I do at work. And because sometimes work can be relatively intensive, it probably takes a couple days away from work before I become Jim the father, as opposed to Jim the businessman. As my children have gotten older, they have reminded me more often by saying things like, “Dad, you’re not at work now.”

Is it hard managing a work/life balance?

Yes. There is no doubt about that. The world of alcoholic beverages is closely associated with the world of entertainment. The company organizes 14,000 events every year. Some are large, like the Golden Globes; some are relatively small, as in tasting dinners for 20 people. I don’t try to go to all of those, that would be impossible, but there’s a lot of planning. When you finish your day in the office, while there is not a necessity to attend events every night, there is a magnetism to some of the events indeed. And I attend and very often speak at some of the events in the evenings. Our head office is six hours ahead in Paris. That’s not a problem for me as I like getting up early. So it’s not uncommon for my day to start at 6:30 a.m., leave here at 7:30 p.m., attend a dinner or event, and get home at midnight or later.

Now, it could be argued that you don’t have to do it all the time, and that is very true. And that’s where the challenging balance of work and life comes in, and it’s something I think all the senior management teams, including my competitors all around the world, have to deal with.

Has there been a favorite or a most memorable event you’ve attended?

My colleagues and I are so fortunate to be involved and present at some magnificent events, and along the way I’ve met presidents, prime ministers, mayors. But there is one event that is extraordinary – the Golden Globes. I think it’s an event where some of the most famous stars on earth relax a little bit under this very social environment where Moët & Chandon is the centerpiece, because everybody is relaxed and having a good time. The actors and the actresses, I think for that day, forget about the fact that they’re actors and actresses and they’re just hanging out together. Nobody seems to be more important than the other. And that includes people like myself. Everyone is treated equally as friends. So it gives you a chance to see incredibly talented people in a very friendly and enjoyable way.

What was it like moving from a large company like Guinness to a smaller company like Moët Hennessy?

I used to think as I was starting my career that big was beautiful, that big was everything. But in fact that’s far from the truth. I think size is almost irrelevant. It’s all about the quality, and the quality of the people you work with. So while Moët Hennessy is not the biggest company in the drinks business in America, we’re probably the most respected. And that’s a combination of having great brands, having I think some of the best people in the industry, which has been borne out by the fact that they’re getting promoted and leading other companies when they leave here, and also that we’re gaining market share, increasing our volumes and profitability in every category we operate. So I don’t think you have to be big to be successful.

What do you look for when you’re hiring?

I think the core element that we look for here at Moët Hennessy is the fit – is the culture which we’ve created here going to work for this individual? The key for me is to make sure we get the right person for the right job, and therefore the culture we’ve created works for everybody. A lot of the people who join us stay for 10, 12, or even 15 years.

We don’t have a lot of attrition now, because we’ve spent a lot of time at this. There’s always a small percentage of attrition, but it’s always for a good reason. People have gone as far as they can go – everybody can’t get my job – so we support them if they feel it’s right to move on and grow their own careers. Frankly, I’ve got to the stage now where I get a big kick seeing people who’ve left us continue to do well.

I have no problem, in fact I enjoy, calling up other industries and saying, “I have a great person here. Would you give them an interview?” Why not? Because who knows. It’s happened many times for me here where they’ve come back again in a bigger and better role. It’s all about the way you treat people as they leave.

What is the difference between promoting a brand regionally versus globally?

I think the key to success for global brands is to really understand the local environment in which you’re operating. While I would not want to claim we look at America as 50 different countries, we do spend an extraordinary amount of time understanding the consumers from all 50 different states. Stating the obvious, the consumer in Miami is very different from the consumer in Chicago. There are as many people in Miami now speaking Spanish as speaking English. The largest population of Polish people in America is in Chicago. There are many counties in Texas today where the majority is Hispanic. If you don’t understand the multi-cultural makeup no global plan will work.

You’ve lived and worked in Belfast and Dublin, San Francisco and New York, how do you compare them?

There is a different style of business between Ireland and the U.S., although I do think Ireland increasingly is becoming more like the U.S. There is not a right or a wrong, but I think business in the U.S. is more about getting it done in real time – less about the social side, more about getting down to business. And I think it makes for a very efficient business model.

In terms of where I worked and lived, my family and I had perhaps the best three years of our lives, at least working life, in San Francisco. I commuted to work on a ferry. And while it was good in the morning, it was particularly good in the evening, because it really helped my work/life balance in that the last ferry would leave at 7 p.m. It was a very unique, very rewarding experience, both from a family perspective and for my career. It launched my career in the U.S., and incidentally I moved to San Francisco for a two-year contract, and here I am 15 years later and now a citizen of the United States.

Why did you want to become a citizen?

As I would get involved in both social and business discussions in America, I found increasingly that I didn’t have the same right to those conversations as people who were citizens; I didn’t have the right to vote. Over the years it became more important to me that if I wanted to be seen and treated as an equal, then I should make the effort to become a citizen.

I think in a way it’s unfortunate that every American doesn’t go through that process because a lot of people born here with the right of being a citizen don’t appreciate just how fortunate they are. Despite all the challenges that America, and every country, has, this is still the greatest country on Earth. Because while I have, and will have forever, a love for Ireland, which always will be my home, we appreciate probably more than most what America did for the Irish people when the Irish people had nothing, when they were dying on the famine ships, when they landed at Ellis Island, and when America welcomed people in with nothing. In America you can come with nothing and become very successful, where you have such an incredible Irish-American community.

You still think of Rostrevor as “home?”

You know, on mature reflection, Rostrevor will always be home. I think that’s happened more strongly in the past five or six years. But I will always have a very powerful affinity to America, and indeed for the rest of my life I’m going to spend part of my life in America, and part of it in Ireland.

How often do you get back?

Thankfully, with quite good regularity. I have a little cottage in Carlingford, County Louth. So when I’m going to Paris for work I fly to Dublin on a Friday night and Dublin to Paris on a Sunday night or a Monday morning, and that gives me a weekend to visit my friends and family. So I’m there five or six times a year. But for no more than long weekends.

But, being part of a large family, it’s never easy, because if you visit one, the others say, “Hey, why did you not come to see us?” It’s a challenge, but it’s a beautiful challenge, because if they didn’t want to see me it’d be another problem. And I wouldn’t say I’ve found the holy grail, but I have, in more recent times, tried to coordinate things like having a barbecue at my cottage or getting all my brothers and sister to come visit me, because at least that way we all get to get together.

What are the most significant changes to the North?

Well, the biggest change is the signing of the Good Friday peace agreement – now you don’t have to worry about security or bombings like we did up until that historic day. But the other thing is that because of that Northern Ireland is now getting direct foreign investment. A lot of major companies are setting up in Belfast. I think despite all the challenges the government has done a good job in redeveloping Belfast. The place is bustling with new hotels and restaurants – we’ve now got 1,000 restaurants in Belfast and more Michelin stars than Manchester, England. It’s a hub of social activity.

What was it like working for Guinness during the Troubles?

Looking back now, it’s hard to believe that we actually worked through some of those terrible days. But it did teach all of us, and certainly we could never give in. We went to work some days, stayed at work some days, when there were terrible atrocities happening. And I sometimes think back and ask myself, “Did that really happen?” But it made me very resilient. When we have normal business challenges here in the U.S. and some of my people are getting a little edgy, I think back to the days I was working with Guinness when we just didn’t know if all our people would make it home. So when we look at a business challenge here, for me, it’s very different. And I think, “Okay, this is a problem. We just have to sit down and figure out a solution to it.”

What that has helped me be, and I’ve been given some nice credits by my colleagues here for it, is that I’m very good operating under stress. Mini crisis management has no fear for me. I’ve dealt with things that are 50 times worse.

What do you think can be done in the North right now?

I would make an appeal to our ministers to sit down, work things out and start building a province that welcomes foreign investment with open arms. We’ve got fantastic education and infrastructure, so let’s maximize that by bringing in high-paid jobs for a highly skilled workforce. Our politicians need to think about not today, but what do the young people of Northern Ireland need 20 years from now.

You are the chairman of Co-operation Ireland. What kind of work do you do?

Yes, I’m involved now 25 years, and I spend most of my time and effort focused on youth and youth leadership programs, because that’s where the future is. On the one hand it’s a wonderful thing, but on the other hand it’s a little sad, because ideally I’d like to shut it down. When we shut it down it means we no longer need it. And when we no longer need it, it means we have reconciliation.

The big challenge for me and for Co-operation Ireland is to give it scale. It costs money to put each person through this program, and I spend most of my time at Co-operation Ireland trying to raise funds so we can put more young people through the youth leadership program.

What is your take on the relationship between the Irish and the drink?

I think that’s a sad relationship, and sometimes difficult to challenge, because it’s very stereotypical. And I meet it a lot. And it’s almost like a joke.

You mean people say it to you.

Yes. I wouldn’t say all the time, but very often. The reality is the majority of Irish people are very socially responsible. The worst thing for our industry as a whole, and for me in particular because I am the vice-chairman, about to become the chairman in February, of the Distilled Spirits Council of the U.S., is to see someone intoxicated. It’s no good. It’s no good for our consumers; it’s no good for our industry. Because that’s not what we’re about. We’re about having a socially responsible drink, either with food, or convivially with friends. So there’s a stereotype of the Irish drinking a lot. I think it’s very unfair. Whatever truth may have been in that 200 years ago, it’s not the modern Ireland. And when I do hear about it I’m quick to point out that we need to be more accurate regarding today’s Ireland, compared to an Ireland of 200 years ago.

Who do you bounce ideas off of now?

Today, I have a boss in Paris called Christophe Navarre, and while he is my boss, he’s the person I sit down and talk to about thoughts, concerns, opportunities, and it’s a very healthy relationship in that we can share in confidence the things we need to talk about. But if it’s an American challenge, an American issue, then he likes us to get on with it. And thankfully, over the years, I’m not afraid to make decisions.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

I think from the tenth year of my 18 years with John Lavery. He said, “Listen, we over complicate this business. And let me tell you what’s important. You can put it in which ever order you like, but there are only two things that matter: people and brands; brands and people. If you think about that, if you get the two things right, most problems turn into opportunities.”

Sometimes in the midst of all the hustle and bustle, I sit down and write it up on my white board: “Brands and People.” That’s it.

It’s Hennessy’s 250th year. What do you think the legacy of Hennessy is?

This has been a particularly great year for Hennessy because of that birthday. And I’m delighted to say we’re having a record year in the U.S. But the legacy I think that comes to my mind immediately is that the Moët Hennessy brands have been involved in every major social and historic occasion that there has been for hundreds of years. You see them in the movies; you see them in celebrations; you see them at the end of sporting events; you see them in music. I guess you could sum it up by saying they have been a part of life. It’s hard to think of life without these brands. I remember reading a story about a great leader who said, “in defeat I need champagne, and in victory, I will enjoy champagne.”

Do you have a favorite brand that Moët Hennessy controls?

I think it’s pretty impossible not to like any one of those brands. I really enjoy Hennessy X.O on the rocks, but I also really appreciate our wine portfolio. And I love our Cloudy Bay, from New Zealand.

I am very fortunate to have such a portfolio of brands, and one of the reasons I’m here, frankly, is if you want to end your career in the alcoholic beverage industry, well, without boasting, there are no better brands on earth than the ones at Moët Hennessy.

Thank You. ♦

It’s a long time since I first met a very young and ambitious Jim Clerkin. My father had a pub in Omagh and Jim was working as a sales representative for the local Irish Bonding Co.and I would meet him weekly. I remember vividly going on a trip to Rome for 10 days along with Jim, several other reps. and a fine collection of other publicans mainly from Co.Tyrone and Fermanagh.It was at the end of Sep beginning Oct 1979. The reason I remember this so well is the Pope was in Ireland at this same time. I have read and thoroughly enjoyed this article detailing some of Jim’s history and present-day adventures and I wish him well in whatever the future holds.

Gerard Mc Gettigan.