The Declaration of Independence is a physically beautiful document and when I was a kid I had an image of it on my wall. There were Irish names, including “McKean” on that original parchment, and that gave me the story I needed to feel at home here like a native. My love of country, the United States, and my heritage (Irish) converge in that document because I acknowledge the Irish who risked their lives to sign it.

Among the citizens who signed what could have been a death warrant were at least eight Irish Americans, three born in Ireland.

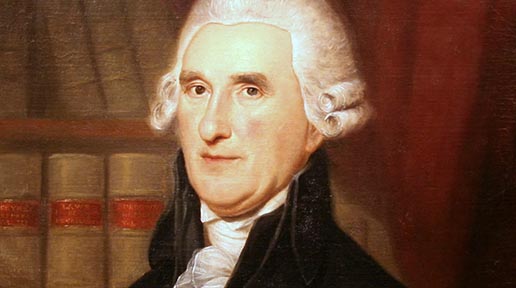

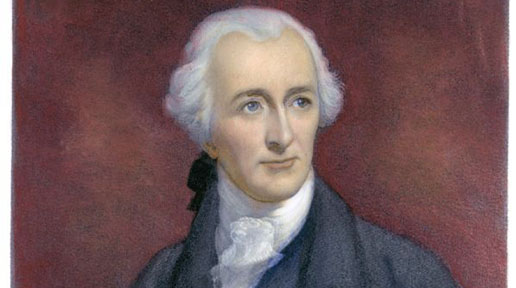

Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734 – June 24, 1817) was the son of William McKean from County Antrim (Aon Troim) who came to Pennsylvania via the city of Derry (Doire) as a child and later married Letitia Finney whose family had also emigrated from Ireland.

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734 – June 24, 1817) was the son of William McKean from County Antrim (Aon Troim) who came to Pennsylvania via the city of Derry (Doire) as a child and later married Letitia Finney whose family had also emigrated from Ireland.

Thomas would become an American lawyer and politician, serving as president of Delaware, chief justice, and then governor of Pennsylvania. During the American Revolution, he was a delegate to the Continental Congress where he signed the United States Declaration of Independence and served as a president of Congress. Thomas McKean led the movement in Delaware for American independence and served as commander of a patriot militia group known as the Pennsylvania “Associators.”

Charles Carroll of Carrollton in Maryland (September 19, 1737 – November 14, 1832) was the only Catholic and the longest-lived signatory of the Declaration of Independence, dying at age 95.

He was held up by Catholic Americans as tangible proof of their patriotism and loyalty in America, which was run by a largely WASP establishment until JFK’s election. He is descended from the noble Gaelic family of Tipperary, Clan Ó Cearbhail, who trace their origins to the Cianachta, a tribe recorded to the third century C.E. He was born in 1737 in Maryland – the only colony tolerant of Catholic emigration, thanks to Lord Baltimore.

James Smith was born in Ireland in c.1719 and was forced with his family to emigrate to the American colonies as a boy due to abuse by landlords. The name “Smith” in Ireland is oftentimes a translation of MacGabhann, which is an older Irish name meaning “son of Goibhniu,” who was the Celtic deity of metallurgy.

Smith emerged as a leading lawyer of his day and wrote legal opinions denying the constitutional power of Great Britain over the colonies in America. He also urged, as Jonathan Swift would do in Ireland, an end to the import of British goods.

He raised a militia group in York, P.A., and joined the American Continental Congress in July 1775, a year before the Declaration was ratified. Smith would become a member of the Continental Congress from 1776-1778, and served in the War of Independence as a Colonel of the Pennsylvania Militia from 1775-1776. He was killed on July 11, 1806.

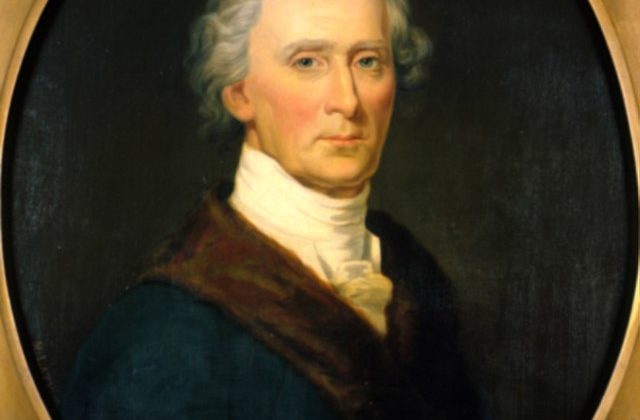

George Taylor

George Taylor was born in Antrim, Ireland in 1716 and emigrated to America in 1736 at the age of 20.

George Taylor was born in Antrim, Ireland in 1716 and emigrated to America in 1736 at the age of 20.

Taylor operated a furnace and was an iron manufacturer in Pennsylvania. He was a member of the Committee of Correspondence, 1774-1776, and of the Continental Congress, 1776-1777.

Taylor is an old name, common in Ireland since the 14th century.

Matthew Thornton was born in Ireland in 1714 and went out to America as a four-year-old child in the passage of five ships carrying 120 Irish families from the Bann Valley (Coleraine-Ballymoney-Aghadowey-Macosquin).

He would practice medicine and become active in pre-revolutionary agitation before being elected to become a member of the Continental Congress in 1776. He was a Colonel of New Hampshire Militia, 1775-1783.

Thornton was sometimes used in Ireland as a synonym for Drennan, Meenagh, Tarrant, or Skehan, while other Thorntons were planted in Limerick in the 16th century.

Edward Rutledge (November 23, 1749 – January 23, 1800) was the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence. His father Dr. John Rutledge left County Tyrone, Ireland in 1735, and would raise a son to be the 39th governor of South Carolina.

In the 2008 miniseries John Adams, Rutledge was portrayed by Clancy O’Connor. With his brother John, Edward Rutledge was elected to the Continental Congress in July 1774.

Thomas Lynch Jr. (August 5, 1749 – 1779) stood in for his father Thomas Lynch Sr. who was unable to represent South Carolina due to illness. His grandfather was Jonas Lynch of the Galway Lynch tribe who was exiled following the defeats at Aughrim and the Boyne.

At the close of 1776, he and his wife sailed for the West Indies. The ship disappeared and there is no record of his life after.

George Read was born in Maryland in 1733. He was the son of John Read and Mary Howell Read. John Read was a wealthy resident of Dublin who emigrated to Maryland. When George Read was an infant the family moved to Delaware.

As he grew up, Read joined Thomas McKean at an academy in Pennsylvania and then studied law. In 1763 John Penn, the proprietary governor, appointed Read Crown Attorney General for the three Delaware counties and he served in that position until leaving for the Continental Congress in 1774.

Dunlap was born in Strabane, County Tyrone. In 1757, when he was 10 years old, he went to work as an apprentice to his uncle, William Dunlap, a printer and bookseller in Philadelphia.

During the American Revolutionary War, Dunlap became an officer in the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry and saw action with George Washington at the battles of Trenton and Princeton.

In 1776, Dunlap secured a lucrative printing contract for the Continental Congress. On July 2, the Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence, and on July 4 they agreed to the final wording of the Declaration of Independence. That evening John Hancock ordered Dunlap to print broadsides. Dunlap printed 200 copies of the Declaration of Independence. The first newspaper outside America to publish the first text was the Belfast News Letter in its edition of August 23-27, 1776. ♦

_______________

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on IrishCentral.com in July 2010. The photos were updated and are all public domain.

I think this page might be anachronistically applying modern ideas about the Irish relationship with the Crown onto the 18th Century. Far from being republican in those times, most Irish were enthusiastic supporters of the monarchy. This is history, go and read it.

I’ve read it and the Irish never accepted British rule and were not supporters of the Monarchy. Perhaps the English planed into Ireland supported it but the native Gaelic Irish – No.

Grouch. Can you point out one fallacy in his facts?

While visiting New Orleans, I learned that only Catholics cold reside in the state of Louisiana, originally a French colony prior to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Very good, young man, most interesting. I’m just writing an article about “America’s First Great Gay General,” but he was Prussian/German, not Irish, the amazing General Frederick von Steuben. I don’t think anyone has ever fully realized the presence of the Irish in world history and culture. It is fun to learn. I’ve been reading quite a bit of Lady Gregory – (O’Grady on one side) and will read more. Thanks for your history article and stick to your guns! That critical guy is so typically Irish. “Go read it!” He’ll be after you with a cane next!

How often are you going to publish this article? Every 4th of July? How about something new?

This is good reading and reminds us of the courage of the early Irish in America. To defy the Crown as they did, meant treason and hanging or at best, long prison terms ….