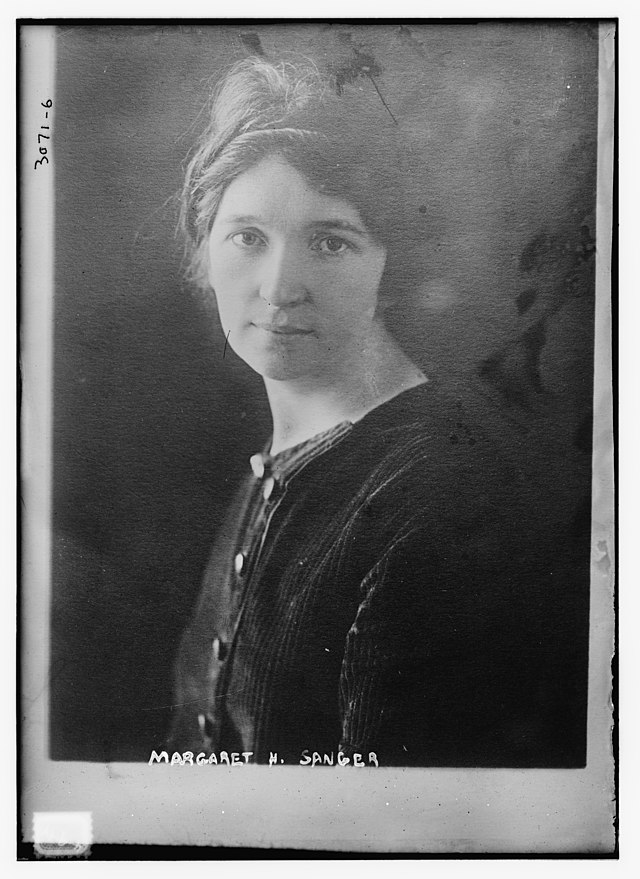

Continuing her series on Wild Irish Women, Rosemary Rogers profiles Margaret Sanger, who devoted her life to legalizing birth control, and with the help of her sister Ethel, opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S.

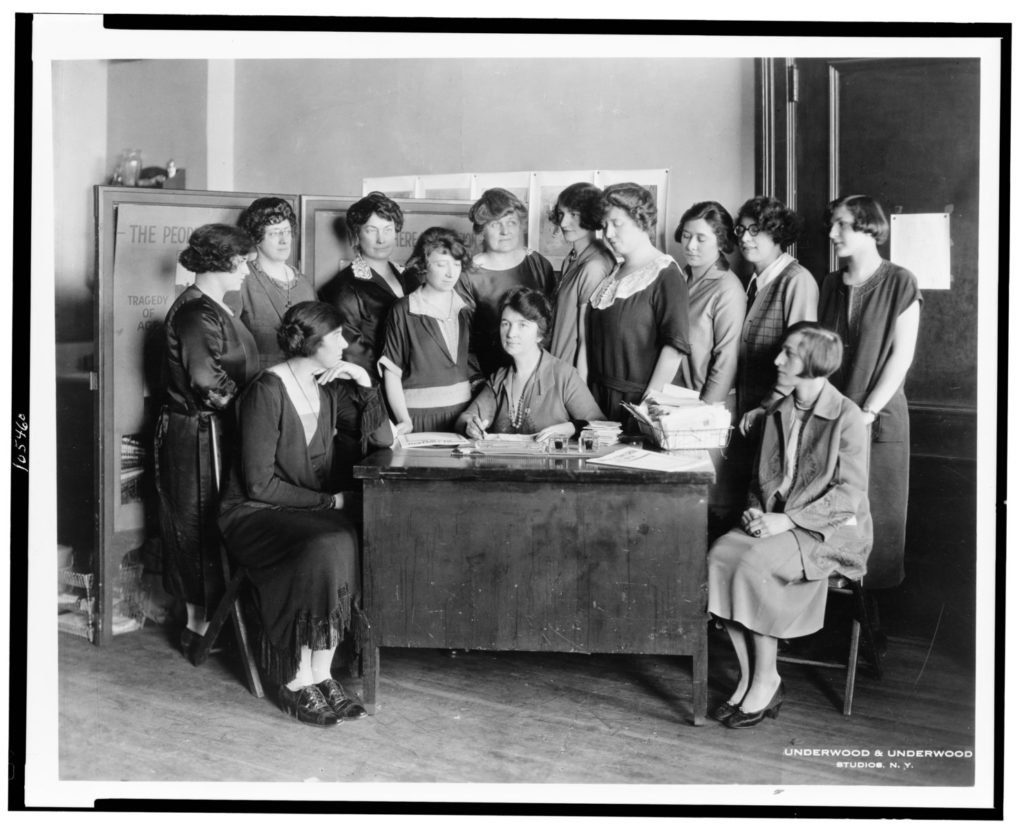

On October 16, 1916, Margaret Sanger opened the doors to a Brooklyn storefront and Planned Parenthood began. The centennial will be celebrated with profound gratitude by generations of women and decried with bile by (too) many male lawmakers. Sanger opened the clinic with two other nurses, her sister Ethel Higgins Byrne and Russian émigré Fania Mindel. Margaret and Ethel were the daughters of Irish-born Michael Higgins and Irish-American Anne Higgins. Michael, an ardent socialist, free speech advocate, philosopher, and prolific father imparted his political passions to Margaret, who fused them with her own brand of righteous feminism.

Five years before she opened the clinic, Margaret, her husband William Sanger, and their children had moved to New York with her sister, settling in Greenwich Village. They fell in with the “Reds” crowd, Emma Goldman, John Reed, Max Eastman, Mabel Dodge Luhan – all socialists, feminists, and free speech advocates. The sisters worked with Fania Mindel in Lower East Side tenements nursing women in labor – starving immigrant mothers, old before their time, already with more children than they could manage. Margaret and Ethel saw so much of their personal story in these women – their own mother had seven miscarriages and eleven children – one delivered by an 8-year-old Margaret – in 22 years before dying at age 49.

By the time Sanger had opened the Brooklyn clinic she was already established as a feminist and writer with her series on “the facts of life,” called What Every Girl Should Know. She wrote and published a magazine, The Women Rebel, in which she coined the term “Birth Control.” A mother of three, Sanger wrote, “The right to be a mother regardless of church or state” was the “basis of feminism.” But everything she had written or planned to write, everything she had done or planned to do, was illegal.

Helping women through childbirth or even watching them die in the process didn’t affect Sanger as deeply as helping women recover (or not) from botched abortions. Sanger nursed one mother close to death after a self-inflicted abortion. The woman pleaded to an unsympathetic doctor for protection against another pregnancy. His advice? “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.” The mother died six months later during a second self-inflicted abortion. Margaret Sanger became a lifelong opponent of abortion and vowed to dedicate her life to making contraception legal, available, and free to those who can’t afford it. A dangerous goal, since thanks to the absurd but powerful Comstock Laws, contraception was illegal, believing it led to promiscuity.

The Victorian villain in all this, and he’s a big one, was a frightful windbag named Anthony Comstock. He was an evangelical Christian, YMCA devotee and head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. He saw New York City as a latter-day Sodom and Gomorrah, a fleshpot of pimps, prostitutes and hoochie-koochie dancers. What choice had he really but to tattletale to the police and summon raids? He railed against French novels and art, once invading the Art Students League to sniff out nude paintings. He tried to suppress George Bernard Shaw’s play on prostitution, Mrs. Warren’s Profession, causing the Irish playwright to gripe (and invent a new word), “Comstockery…the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States.” For some odd reason, Comstock found information about birth control particularly pornographic and began his crusade against the contraception industry. He persuaded Washington to create an anti-obscenity bill banning contraceptives, the eponymous Comstock Act which went into effect in 1873 and was used to persecute Margaret Sanger for decades.

1914 and 1915 were trying years for Sanger. Her marriage had unraveled, her 5-year-old daughter Peggy died of pneumonia and her articles on sex education got her arrested, forcing her to flee to Europe. The charges were dropped when, in a rare burst of humanity, the court decided that no judge would sentence a grieving mother. Margaret Sanger came back to New York even more determined. Now was the time for the Brooklyn clinic.

The first day brought over 100 women lining around the block, pushing prams, holding infants, and keeping toddlers in tow. Margaret, Ethel and Fania distributed contraceptives and copies of Margaret’s pamphlets, the only information these women had ever seen about their own anatomy. The nurses heard over and over the question poor women always seemed to ask about rich women: what’s their secret? Why don’t they have a baby every year? The “secret,” of course, was contraception.

Then as now, Planned Parenthood was and is about information – education on family planning, pregnancy, sexually transmitted disease and understanding how contraception works. Then as now, it was/is the only health care available to women living in poverty. Then and now, it wasn’t/isn’t an abortion mill depicted by crowing moralists like Anthony Comstock of the late 19th century and Scott Walker of the early 21st century.

The clinic wasn’t opened long when a distraught Mrs. Whitehurst, desperate to avoid another unwanted pregnancy, sought and got help from the nurses. The distraught Mrs. Whitehurst was an undercover policewoman. Ten days after it opened, the vice squad burst in and lugged out an examining table, an assortment of contraceptives, “books on young women” and shut the place down. Sanger, Byrne, and Mindel were arrested on obscenity charges under the Comstock Act. All were found guilty, all remained unafraid – even as they awaited trial, they re-opened the clinic two days later, were again raided, re-opened one more time until the police forced the landlord to have them evicted.

In prison, Ethel, her mind on her father’s stories of Irish freedom fighters and hunger strikes, went on one herself. She was close to death, and even the press begged for her pardon. Margaret helped secure her early release by promising that Ethel would never break this law again; this angered Ethel and the two sisters were never as close again. No longer active in the birth control movement, Ethel died in 1955 from a heart attack.

Margaret went on trial to make her case – exposing women to the danger of dying in childbirth was a violation of their right to life. In the courtroom, she had the unfortunate experience of having a judge wave a cervical cap in her face and announce that no woman “had the right to copulate with a feeling of security.” Offered her freedom if she promised never again to break the law, Sanger replied with a curt, “I cannot respect the law as it exists today.” Convicted, she was sent to the workhouse. But she succeeded in getting attention and the support of the public, a development that a reporter later attributed to her “Irish ancestry, which endowed her with unfailing charm and persuasive wit.”

Out of the workhouse, Sanger appealed her sentence and won. A new judge issued a ruling allowing doctors to prescribe contraception in New York State. Pushing the envelope further, in 1917, she starred in a silent film, Birth Control. It was, needless to say, banned and now she slowly began her shift away from radical politics. In 1921, she founded the American Birth Control League and, in 1923, opened the first (legal) birth control clinic. To get her message across to the Establishment and to the middle class, Sanger campaigned all over the U.S. and Europe. She began consulting with scientists trying to develop a “magic pill,” one that women could take before they were ready to be a mother.

Margaret Sanger had remarried and moved upstate close to where her niece and Ethel’s daughter, Olive Byrne, lived. Olive had come under the sway of William Moulton Marston, an oddball psychologist, screenwriter, and most significantly, the creator of Wonder Woman. Marston lived with his wife, Olive, and the children from both women; the unconventional “family” had frequent visits with “Aunt Margaret.” Wonder Woman, the first female super-hero was according to Jill Lepore, author of The Last Amazon, Wonder Woman Returns, “a pinup girl. She’s Eleanor Roosevelt. She’s Betty Grable. Mostly, she’s Margaret Sanger.”

In 1937, the American Medical Association endorsed contraception and by the 1950s, research and development on “the magic pill” began in earnest. Margaret Sanger, aged but still the activist, brought together scientist Gregory Pincus and wealthy feminist Katherine McCormick, and, in 1960, the “magic pill” was on the market. In 1965, the year before Sanger’s death, 6.5 million American women were “on the pill” and the Comstock Laws were, finally, thrown out by the Supreme Court. Justice William O. Douglas announced the decision, paying tribute to Wonder Woman – “I am sure Mrs. Sanger, who is very ill, will rejoice in this which crowns her 50 years of dedication to the liberation of women.” ♦

When I read the story of Margaret Higgins Sanger, (Wonder Woman, August/September) and her pioneering efforts in the early 20th century to make contraception legal and available to all women, l was reminded of my mother ‘s views on this topic.

Mary Carmelita Donohoe Lyons , mother of seven children, a granddaughter of Irish immigrants from Co West Meath, would climb over snow banks to get to daily mass at her parish church up until two weeks before she died at age 93 in Yankton, South Dakota.

Mother visited our home in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1984 shortly after Bernard Law had been installed as Archbishop of Boston. In his inaugural address, Law decried pro-choice women as “the greatest evil of our time.”

I asked my mother what she thought about the archbishop’s charge against women. She snapped her fingers and instantly replied: “Well, they can’t have it both ways. You can’t deny a woman the right to decide whether or not to conceive and then expect her to live with the consequences.” And then, my mother, who not only knew her mind well, but could speak it well added: “I think it’s time for those Bishops to get off their high horses.” That was very strong language from a devout Catholic mother. I told her that I thought she was a better theologian than any bishop.

If my good mother were alive today, I am quite certain she would repeat the same charge to the Bishops.

Thanks for presenting the story of the wonder woman at the beginning of the 20th century and for reminding me of another wonder woman, toward the end of that century, my mother.

Robert F. Lyons,

Kennebunkport, Maine

See here what Margaret Sanger really said about eugenics and race, https://time.com/4081760/margaret-sanger-history-eugenics/.