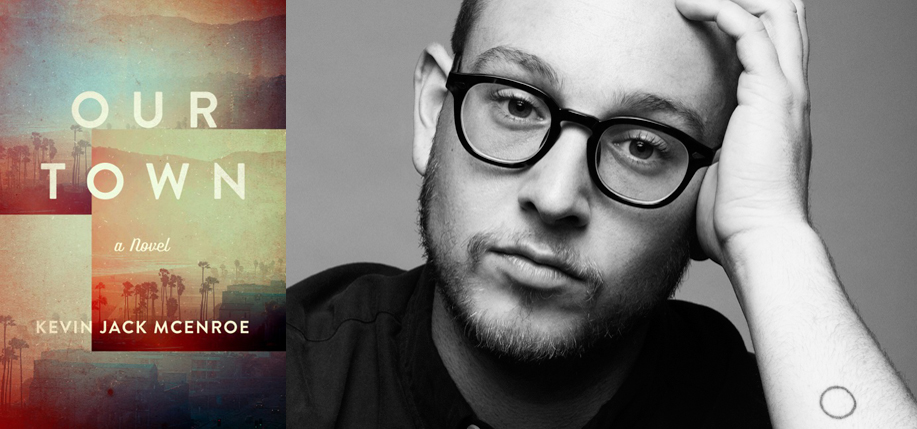

At 29, Kevin Jack McEnroe calls his grandmother, the actress Joanna Moore, his “guardian angel.” He credits her, and his debut novel Our Town, a fictionalized account of Moore’s life and struggles with failed relationships and substance abuse, with helping him come to know himself better. So much so that got a tattoo of her on his left arm just after the book was published.

Moore (named Dorothy White in the novel, a reference to her full given name of Dorothy Joanne Cook), along with actor Ryan O’Neal, are the parents of actress Tatum O’Neal, McEnroe’s mother. His father is the famed tennis player John McEnroe. Both his grandmother and mother lost custody of their children as a result of substance abuse and were often the subjects of tabloid articles.

All of this, however, situates him nicely to write the intimate novel this is, that lifts the tabloid curtain on the darker side of Hollywood and personal defeat – something McEnroe knows himself. The same day he was offered, but had not yet signed, the book deal, he was arrested for trying to buy cocaine in New York, and ended up on the front page of The New York Post the following day with the headline, “Family Curse: McEnroe & Tatum kid in drug bust.”

After rehab and a year off drugs now, he acknowledges Joanna, as he calls her, familiarly, has been a significant part of his professional writing career from the start. Though they only met once when he was five, that meeting became the genesis for this novel. As an undergraduate, he was assigned to write a story from the perspective of the opposite gender, and he took Joanna’s.

“I wrote this story that was about this grandmother and her grandson and the way he viewed her and looked up to her, as if he was the only person in the world who might do that,” he says. “From then on I kept coming back to that character, and a version of that first story has been in the book since.”

That compulsion to return to Joanna comes through in the unique narrative voice of the novel, which might be described as urgent, but casual familiarity, with the tics of an oral history. It is one of the most compelling aspects of this debut. When we meet at a small coffee shop around the corner from his apartment in Brooklyn, this is where we begin.

℘℘℘

I’m fascinated by the narrative voice. It felt like the narrator had to tell this story, but also that it had already been told.

Right, that it’s very important. My initial instinct in writing the book was that the story of my grandmother is just a cautionary tale of “this person is just a fuck up,” and I thought there was more to it than that. So perhaps you think you know this story, but you don’t know this part, and maybe this part is actually the most important.

There was something about her ability to not believe in herself. To be close to success but then believe she didn’t deserve it, and to screw it up and get in her own way. That’s a theme of the book – to constantly get in your own way. And that was the thing that I eventually felt like I understood about her. Because I had felt like I had that too. And it made me really empathize with her. And I hope that came through.

What research did you do for the book?

My mom remembered that later in her life Joanna used to write short stories. She’d never told me that, and she found a big binder of her writings. That was the most significant research I did – to read all the way through those and try to figure out how Joanna’s brain worked.

Even in her diary she had this ability to disassociate herself from the actuality of the situation – she’d be losing her kids in custody battle and yet be writing things to herself like “lost four pounds today” and “skin looks beautiful.” So she actually has – I’m sure drugs and alcohol really allow for this – this ability to disassociate from the actual reality and just sort of be in the exact moment she was in. And in fact I know that drugs and alcohol do that. Drugs, specifically, can allow you to feel like you’re living just for that and those moments where you feel happy and everything else falls away.

I thought she was just a failed actress, I had no idea she had this secret passion for wanting to tell a flowery children’s story about happy kids and good parents – kind of an alternative history for her own life. And that’s what I knew this needed to be – not taking her stuff, but the idea of honoring her in that way.

Did writing this book affect your relationship with your parents? Your mom, specifically?

It made it better. She didn’t read it until I had a galley and she read it and she called me crying and told me Joanna would love it. I think Joanna was viewed as this cautionary tale, and my mom even felt that way for a long time, too, wondering, “Why are you choosing drugs more than your kids?” But it’s not a choice at that point. You don’t think in those terms. One of the things that happened when I finished the book was that I was able to actually understand my mom and the fact that it’s not a choice. And that made me able to forgive her, which made us even closer. And I’m very happy about that.

It’s almost part of the book’s mythos now that you were offered the book deal the same day you were arrested. Did that change your conception of how the novel would be shaped?

I took it a lot more seriously. I spent 20 hours in jail, in the tombs, holed up, and it was just unbelievably horrendous. I was so down on myself and thinking, “Oh God, I’ve done this. I’ve screwed my dreams up and everything I’ve ever wanted is falling away from me.”

But Joanna’s really my guardian angel. I’m not religious, but there was something sort of cosmic about saying, “Okay, this is still real, I need to, for her, take this seriously, take my life more seriously, and cobble together something that really means something.” I became more empathetic to her, so the book changed from being this semi-factual account to me feeling like I understood her even more – and myself even more, and the fact that I couldn’t do that anymore – and it became maybe more of a love story to her. I think it always had some of that, but I came to believe that this needed to honor her because she saved my life.

The first line I wrote after I got arrested was “But she always got in her own way. She never quite figured out how to get out of her own way.” And I thought this is what the book is about. That’s what the narrator has – everything has to come back to that. That is something she doesn’t even understand herself. But now I do. And the narrator does too. And if she had only ever realized this is what she had, she’d be able to fix it. But she thought it was so many other things.

And you feel that’s something inherited?

I do, just because Tatum has it, Joanna has it, more so even than drugs and alcohol. And I think I finally fully realized then why I was so interested in Joanna. I put two and two together and I realized I was really writing about the fact that she had something inside of her and that she had passed that down to me that is just sort of an inability to get out of your own way at times. And once I knew that was in me, I could think, “Oh, I know what that feeling is,” and every time I feel that I can stop.

How do you do that now?

I just know what it is. And I was never able to recognize it before. I just thought I was making specific mistakes – one thing would happen, and then another, but there was no link as to why. But now I’m able to see the pattern. And when I really figured that out is when I was able to create a thesis for the book. So that’s why I can’t really say I regret it all. In fact I think it’s one of the best things to ever happen to me.

Yeah?

Yeah, because it changed my life for the better. I probably could have casually done drugs for years like everyone else I know. But drugs allowed me to not be particularly productive and got in the way of things. So now I have a strict no-drug policy and it’s been pretty good.

I looked back and realized that I always did drugs when I was uncomfortable. If I was out somewhere I didn’t like, that’s when I would always say, okay, lets get some drugs. And now I feel like if I go to places where I’m comfortable, I don’t even think about it. And that really has been a very positive change.

I’d love to hear more about your attention to detail. Some of the ways you describe Dorothy’s clothing, or the process of her putting on makeup, or even what she herself is noticing, it seems like a key into her psychological state of mind in that moment.

To be honest, it bogs a lot of people down, but what I wanted to get across was a sense of set design, and the way the characters view the world. And the way the chemicals are getting in the way of how the characters view the world – to constantly exhaust you. The dissociative element to Joanna’s stories had a lot to do with that, too – the characters are pushed away from how they feel by focusing on other things.

And I also feel like it was a tactic for me, as the writer, to see if I can distract you enough so as not to feel like Dorothy is a bad person. I never felt like she was a bad person, but I thought some people might. But I felt like the readership I have would, hopefully, over time, relate to her, and feel like there’s something about her that is lovable. And I want her to shine because she doesn’t know how to.

I think what the book does a really good job of is creating a good sense of tragic sympathy for Joanna.

I think it’s that we all have some of that in us. We all have ways we can screw up our lives. Really it’s that feeling of knowing you’re doing something wrong but you do it anyway. And hasn’t every person in their lives done that once? Even if you’re dieting, and you say, “I’m on a diet but fuck it.” And it feels good. Imagine that. Shine a magnifying glass on that feeling, and that’s how you live your life – “I’m losing my kids but fuck it. I can go have a drink now.”

But I feel like everyone I know, or at least everyone I care about, has that in them. And it’s tragic to go through your entire life and never realize that you’re worth more. And I do want people to love her. Because I, or at least the narrator, loves her – there’s a lot of love there. And I believe in her. The narrator believes in her. And I want everyone else to. ♦

Leave a Reply