In rural Virginia, where poverty is a constant and medical care is a rarity, a team of nurses has provided mobile healthcare for 35 years. Today, the Health Wagon provides more than $1 million worth of medical care to more than 11,000 uninsured or underinsured patients who would otherwise have no access to the services they need.

Through rolling hills, a red 1968 Volkswagen Beetle putters up and around the curving narrow roads of Appalachia, past gravel drives of overlooked addresses. It’s 1980, and Sr. Bernadette “Bernie” Kenny is making her way through several southwest Virginia communities, hidden by nestled valleys and a canopy of storytelling trees, providing free healthcare services from her back seat.

“She made her way through the area in the 1980s when the concept of nurse practitioners was very foreign. She saw the need, and she saw people hurting, so she came and she did something about it. Even saying she’s a hero does not describe it,” said Dr. Paula Hill-Meade who serves as the clinical director at the Health Wagon, a nonprofit organization founded by Sr. Bernie.

Sr. Bernie grew up in Boston and entered the order of the Medical Missionaries of Mary in 1957. She spent five years in Ireland, completing her original nurse and midwifery training in our Lady of Lourdes hospital. After returning to the U.S. for a short time, she went on to serve in Tanzania for 10 years as a midwife delivering babies, then moved to Southwest Virginia in 1978 by request of the Richmond Diocese.

“I was frustrated because of legislation and regulations,” Sr. Bernie said. “So, I went to school to train as a nurse practitioner, and that’s when I thought about a mobile unit. Before that, I had been visiting patients in homes and used a Volkswagen Bug to carry around supplies and whatever medications I could.”

Her vision turned into a reality in 1982, when the Health Wagon was officially founded as a single mobile unit, traveling through small towns to community locations and even providing care in families’ backyards to the medically underserved populations of Southwest Virginia.

“We are now broadening the concept of health,” Sr. Bernie said. “The healing touch inspires people to make big changes that often have to happen in the person’s life, and also in their family’s lives.”

From preventative care, women’s health, and chronic disease management (the list goes on) to parenting classes, economic health, and even technical education, the Health Wagon has become an invaluable lifesaving resource across the five main counties it serves and beyond. Last year alone, the Health Wagon managed close to 14,500 patient encounters through its programs.

“We feel that we are only reaching the tip of the iceberg – the need here is phenomenal as health care needs outstrip available resources,” explained Dr. Teresa Tyson, Executive Director of the Health Wagon. “It is a poor resource area with a lot of poverty. Sometimes, it’s hard to believe that healthcare disparities of this proportion are occurring in the United States. We see the brokenness of humanity here daily at the clinic.”

In 2014, the Health Wagon expanded to include two mobile units and one stationary clinic. 2015 followed with an innovative undertaking, as the first FAA-approved drone medication delivery was accomplished in a joint venture with Remote Area Medical (RAM). Then in 2016, the Health Wagon team completed the first telemedicine bladder cancer screening in the world, performed as a joint venture with the University of Virginia. 2017 wrapped up with the first Army Readiness Training event in Virginia, as well as the addition of veterinary services.

“It’s been phenomenal,” Tyson said. “We keep adding resources that we did not have before.”

The Health Wagon continues to participate in and host several RAM events each year, where Sr. Bernie can be found volunteering her time and services. “I’m still learning, that’s for sure,” she said.

As Sr. Bernie approaches her 80th birthday – a milestone of her own – the Health Wagon is preparing to celebrate a milestone of their own in her honor. They are set to open another stationary clinic – to be named the Sr. Bernie Kenny Clinic – funded primarily by an Appalachian Regional Commission grant.

This clinic will host several of the organization’s growing initiatives, such as vision care, telemedicine, and the application of diagnostics through the use of a new ultrasound machine (donated by Philips Foundation through a partnership with RAD-AID). Tyson hopes that these new programs can service widespread needs such as diagnostic testing, prenatal ultrasounds, and diabetes care, among others.

Starting in 1982, the Health Wagon was operated from a Winnebago RV, which was donated by St. Mary’s Hospital in Norton, Virginia. Just before filming began for an April 2014 edition of “60 Minutes,” featuring the Health Wagon, the Winnebago gave up – prompting the need for something new.

Since then, a 4,900-square-foot temporary stationary clinic has been set up, and in the fall of 2014, the organization unveiled its brand new Mobile Unit on campus at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia.

Hill-Meade and Tyson, who have been friends since they were just 14 years old, both grew up in southwest Virginia and have seen the ebbs and flows of poverty and medical care in the area. “What hurts me the most,” Hill-Meade said, “is that on this anniversary of the war on poverty, we can tell you that things are worse now than when we were children in the 70s.”

“We want to be the hands of Christ in some small way,” Tyson said. “Paula [Hill-Meade] and I found mission work right here in our backyard. We’ve had some wonderful influences in our lives – but Sr. Bernie is our mentor. She taught us firsthand about social justice, and we are forever indebted. As two Appalachian women, we will be able to carry that on into the future.”

The Health Wagon is funded primarily by donations and grants, and the small 19-person staff consists of one registered nurse, two licensed practical nurses, two full-time certified family nurse practitioners, and an administrative team.

Teresa Gardner, the Executive Director of the Health Wagon, began working in 1993 as the Health Wagon’s first employee. She was a newly graduated nurse at the time, but by 2006, Sr. Bernie had turned over the reins to her.

“I attribute a great deal of our success to Teresa,” Sr. Bernie said. “She has a great vision and a lot of energy to put into it. It was the first job she had. The crunch was on at the time; we had to not only deliver the healthcare but also do the fundraising and the administration. She has really always been a fresh set of eyes.”

Gardner is originally from the small town of Coeburn, Virginia, where the population is just over 2,000. Coeburn was also home to her right-hand woman, Paula Hill-Meade, who serves as the Clinical Director for the Health Wagon.

Along with all of their administrative responsibilities, Gardner and Hill-Meade both continue to serve as active nurse practitioners, giving direct primary care to patients on a weekly basis.

“Although we are a charitable clinic, and our services are free, it costs us to do what we do,” Hill-Meade said. According to Gardner, the Health Wagon currently runs on nearly $800,000 a year.

Services provided are often primary and preventative, including the treatment of ailments such as sore throat, urinary tract infection or simple immunizations. The focus of the organization, however, is on chronic disease management for conditions such as hypertension, mental illness, COPD, and others.

“God has just blessed us in that we have been able to expand on what [Sr. Bernie] started 35 years ago because the need is certainly here,” Gardner said.

“It was a dream of mine to offer healthcare to people in their homes because you learn so much from how people live. The root cause of illness very often is in the lifestyle, and people don’t choose to be ill, but there are many things that they don’t have too much control over,” Sr. Bernie said. “I went to the homes of people and started to build trust.”

Many of their patients are middle-aged women such as 39-year-old Tracey Salyers, also a resident of Coeburn. Salyers has been going to the Health Wagon for over five years to treat her type-2 diabetes.

“It’s something that’s needed everywhere, but here you find a lot of people who are – I don’t want to say poor because we are rich in a lot of ways – but the economy isn’t exactly booming. I don’t think it’s needed specifically in the Appalachia area; I just think that we were graced enough to have Sr. Bernie start it here.”

Salyers is a mother of five, all of whom are covered under their father’s healthcare. Salyers, however, is not included in that plan at an affordable rate. Because of that, she now turns to the Health Wagon every two to three months as her primary caregiver for check-ups.

“We’re a really close-knit community, and the Health Wagon is a very family-oriented space. You feel comfortable there with the caregivers because they know you or get to know you,” Salyers said. “You’re not just someone that’s waiting in line to see them and then you’re out the door.”

Sr. Bernie grew up in a large family as well, as one of five children raised by a first-generation Irish-American family. She graduated from Boston College School of Nursing magnum cum laude and found herself traveling to Appalachia by request of the Richmond Catholic Diocese.

Rooted in agriculture, mining, family, and religion, Appalachia reminds her of old Irish stories that she was raised on, according to Sr. Bernie.

Southwest Virginia can also be known for its character, its history, and, unfortunately, its destitution.

The area that the Health Wagon covers, which started with five communities but is now up to 12 communities, has a poverty rate that is 70 to 140 percent higher than the rest of the state of Virginia. That includes many of the 1 million Virginians who cannot afford Healthcare.

“Many people don’t have insurance or the diagnostics that they need readily available,” said Gardner. “It’s tremendously important in our location because every patient that we serve is immensely underserved. There’s just huge access problems with healthcare in general in the United States, so being able to provide patients with access to care and actually taking the care to the patients is vital.”

“Nobody seems to even know about this population that is a huge part of Virginia,” added Hill-Meade. “Compared to northern Virginia or Richmond, or places like Fairfax that is one of the wealthiest counties in the nation, we feel like the commonwealth has forgotten us down here. All my life I’ve heard the saying that Virginia stops in Roanoke…it doesn’t seem like anybody is aware of the extreme amount of poverty and desperation down this way.”

The area has had a long-time reliance on coal mining, and to this day the industry has a tight leash on the local economy – in turn affecting the Appalachian population. The 15.3 million tons of coal produced in Southwest Virginia each year may bring money to the area, but they also bring health issues.

“Here, we have a high rate of pulmonary diseases. I think it’s directly related to the environmental effects of not only the coal mines but the coal trucks, the dust, and the pollution in the air,” Hill-Meade said. “We have a high rate of allergens, a high rate of asthma, and a lot of people diagnosed with black lung that have never seen the inside of a coal mine.”

“There’s coal everywhere you look here in Coeburn, so it is something to be concerned about,” said Salyers. “I don’t say a whole lot against the coal because it puts food on our table – and that’s the biggest issue around here. What’s the one job that you can get that’s gonna pay the most in this area? Coal mining. Everybody around here is attached by coal in one way or another.”

Recently, however, the coal industry has sent more and more patients to the Health Wagon, not necessarily because of health issues but because of layoffs and loss of health coverage.

Southwest Virginia produces half the coal it did ten years ago, according to the State Department of Mines, and hundreds of mining employees have been laid off in the process. During layoff periods, the Health Wagon sometimes sees up to 100 patients per week between the mobile unit and the stationary clinic.

“The Health Wagon is so overwhelmed after the coal mining layoff that we’re getting more and more people every single day,” said Hill-Meade.

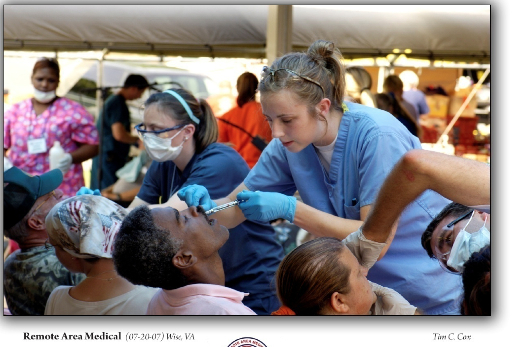

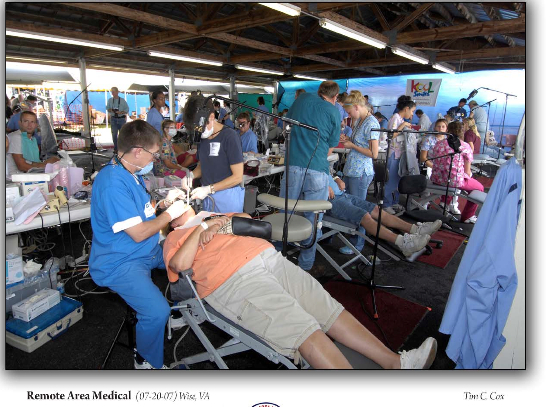

Gardner and Hill-Meade agreed that because of the layoffs, they are also expecting a surge in attendance for their 16th annual Remote Area Medical Weekend, or “RAM,” an annual event known as the largest medical outreach in the United States.

Every July, RAM takes place in Wise, Virginia, at the Health Wagon, delivering basic medical care to people in the area.

“People come from Florida, Michigan, and even farther for RAM,” Sr. Bernie said. “They camp in their cars overnight and wait. We offer state-of-the-art services like ultrasound and retinopathy, oral surgery, or colonoscopies for free; it’s amazing.”

“It’s an eye-opening experience,” Hill-Meade said. “We keep adding services and we keep doing collaborative agreements with universities to bring more essential services each year. These people don’t have access to these services, and they wait all year long to be on the waiting list. We have hordes of people coming out to get basic medical care, vision care, dental care…it’s amazing, horrific, and depressing to think that they’re this desperate for care.”

According to Gardner, the Health Wagon is a medical home for about 3,000 patients, but during the RAM weekend, they mostly see new and one-time patients.

Although she is retired now, Sr. Bernie still helps each year with RAM. “We live in a commonwealth, and we hope one day it will be a ‘commonhealth.’ We are our brother’s keeper or our sister’s keeper,” she said.

Aside from the annual expansion of RAM, the Health Wagon also has plans to expand its pharmacy, as well as build a permanent stationary clinic and raise awareness.

“We’re on the road to getting the education and understanding of self-care improved greatly,” Sr. Bernie said. “The most important thing to understand is that we’re experiencing a ‘brain drain’ – just like in Ireland years ago, the people who leave here often haven’t come back.

“All of the people from the area that we send to places like Virginia Tech don’t come back, so we would hope that in the future there would be more education for people and jobs that they can come back to, to improve the health systems here,” Sr. Bernie continued.

Currently, the ratio of people to primary physicians in Virginia is 1,344:1, while that ratio sits at around 4,000:1 in southwest Virginia – and according to Sr. Bernie, those are important numbers to focus on.

“The Health Wagon actually brought healthcare into a practical aspect. This is an innovative model for healthcare across the United States without the political fiasco that our Affordable Healthcare Act has become,” Hill-Meade said.

“Sr. Bernie has a wonderful spirit of passion and this exquisite ability to care for others that is unparalleled by anybody I’ve ever seen,” added Gardner. “What she started here in the Appalachian Mountains was certainly ahead of its time; she was really one of the front runners of this type of care.” ♦

Editor’s Note: Sister Kenny, who was honored by Irish America in 2018, passed away on December 7, 2024, just an hour shy of her 86th Birthday. To learn more about the Health Wagon and read tributes to Sister Kenny, see here.

This article was first published in 2015 and updated in 2018.

Leave a Reply