Award-winning Irish American novelist and devout Catholic Flannery O’Connor will appear on a new postal stamp, joining distinguished authors like Hemingway and Steinbeck in the “Forever” U.S.P.S stamp series.

Famous for her unnerving southern fiction style, O’Connor’s absorbing work deals with the ideas of racism, free will, sexism and inevitability of belief. Her autobiographer, Brad Gooch, explains O’Connor was uninterested in making people happy or comfortable. Rather, she focused on the political realities of her time. Her approach proved to work as a collection of her works, The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor, won the 1972 National Book Award for fiction.

According to Linn’s Stamp, the non-denominated three-ounce-rate stamp was issued June 5th, during the NAPEX Stamp Show in McLean, VA.

The stamp itself depicts a digital portrait of O’Connor (taken when O’Connor was a student at the Georgia State College from 1942 to 1945), created by artist Sam Weber. Surrounding O’Connor are peacock feathers, the Los Angeles Times reports, the feathers are a symbol of O’Connor’s fondness for the exotic bird, from raising them on her family farm in Georgia. The article reprinted below, originally published in the March/April 1998 issue of Irish America, discuss O’Connor’s upbringing and the affect her Irish heritage has impacted her writing.

Although, O’Connor’s life was cut short (passing at age 39, from lupus disease), her legacy lives on. Her inclusion into the U.S. postage stamps is a triumph for American authors and a major step for Irish American writers. – Cliodhna Joyce Daly

℘℘℘

“Flannery O’Connor: An Irish American Literary Giant”

Novelist and short story writer (Mary) Flannery O’Connor, who specialized in calling attention to the spiritual shortcomings of her characters, was born on March 25, 1925 in Savannah, Georgia. O’Connor was witness to a rapidly accelerating process of change that brought the destabilizing and depersonalizing effects of industrialization and agricultural mechanization to the rural and small-town South. A Roman Catholic, she viewed with critical detachment the entrenched, obsessive, and, in her portrayals, often hypocritical and hollow devotion of her fellow southerners to fundamentalist Protestantism. O’Connor died in 1964 at the age of 39 of a debilitating disease and left behind dire, funny, magnificent stories. Her death deprived American letters of a brilliant writer.

_______________

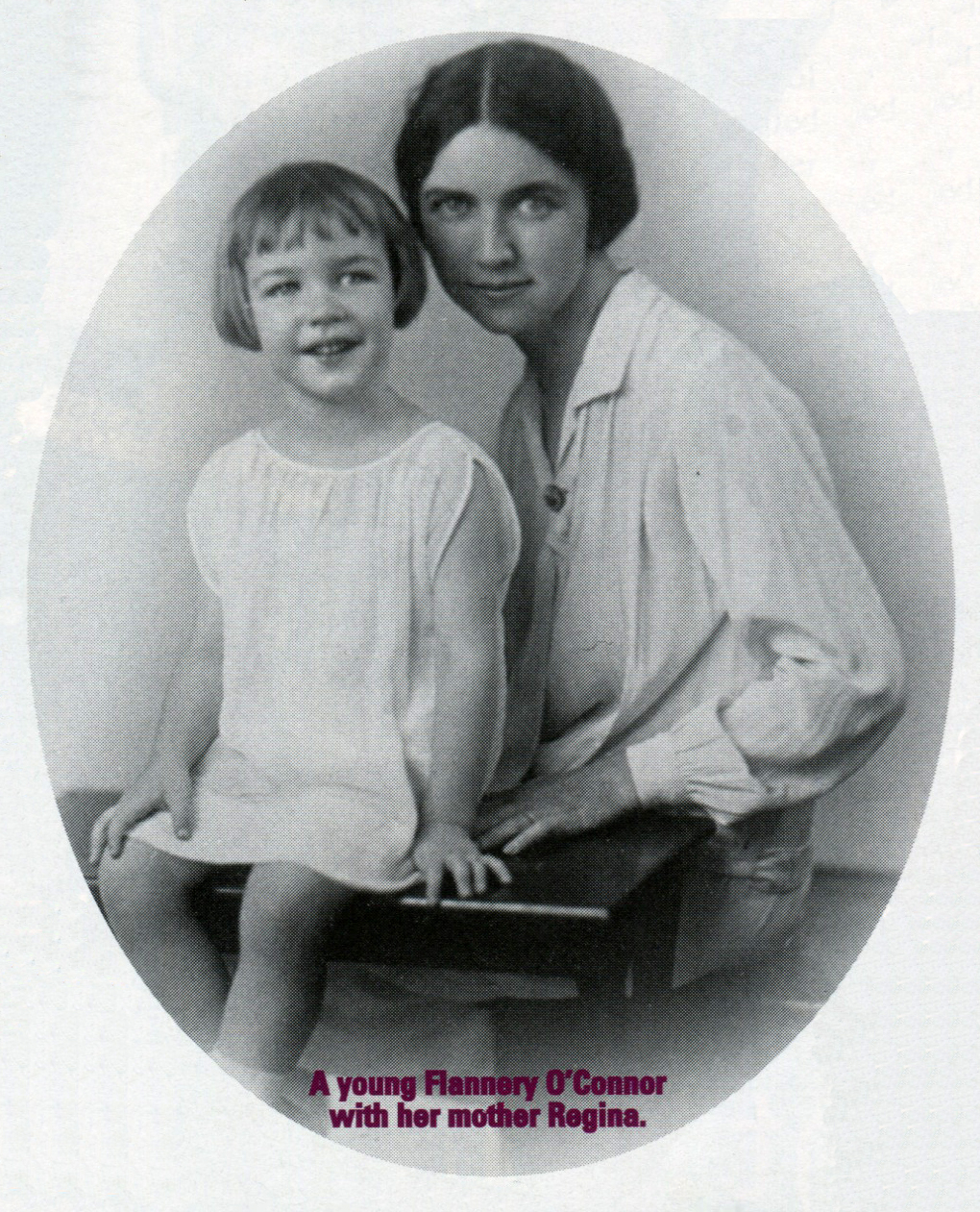

O’Connor’s great-great grandfather, Patrick Harty, came to Georgia in 1824 from county Tipperary, settling in Taliafero County. Edward O’Connor, the author’s father, attended Catholic schools as a boy and eventually married Regina Cline. In time, they became the parents of a girl whom they christened Mary Flannery O’Connor.

“‘Flannery sounds like something to eat,’” someone once commented. The words reminds people of flannel, the soft woven cloth used to make nightgowns and winter shirts. It is very Irish. O’Connor never used her first name.

She was an Aries, born March 25, 1925. When O’Connor was 16, her father died of lupus, the disease that, years later, killed her. After her father died, O’Connor and her mother moved from Savannah to Milledgeville, where they lived in a townhouse built for Flannery O’Connor’s maternal grandfather, Peter Cline.

O’Connor attended local Catholic schools and then Georgia Women’s College in Milledgeville. In 1945 she received a fellowship to the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa, from which she received a M.A. degree in 1947. While still a student, she wrote stories that caused her to be recognized as a writer of considerable talent. After stay at Yaddo, the artists’ colony in upstate New York, O’Connor moved to a furnished room in New York City. Later, she lived and wrote in an apartment over a garage at the Connecticut home of Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, who became after her death, her literary executors.

After a period of doubt, she reaffirmed her loyalty to the Catholic Church. What might have seemed a causal decision, since she had been brought up in a Catholic family, involved every part of her being.

O’Connor eventually decided to spend the remainder of her life in Milledgeville. She believed that this decision saved her from the rootlessness from which, she felt, many of her contemporaries suffered. O’Connor recognized that, for the artist, the entire universe exists in the gestures of individuals, and the individuals she knew were southern.

Early on, Flannery O’Connor faced the almost certain prospect of a deterioration of her health, leading to a premature death. In December 1950 she experienced a heaviness in her arms. On the train trip home from Georgia for the Christmas holiday, she became so ill she had to be hospitalized. The cause of her problems was diagnosed as disseminated lupus.

The word lupus is Latin for “wolf,” and has been described as a disease “that eats into the substance.” It is a painful, wasting malady, O’Connor not only suffered from the disease itself-which caused her muscles to weaken and her body to swell, among other things-but from the medicine she took to fight it, which caused her hair to fall out and her hip-bones to melt.

O’Connor’s comments on her illness were often humorous, sometimes merely descriptive, occasionally philosophical, almost never self-pitying. She did on rare occasions reflect in her correspondence on her illness.

In a letter written to a person known only as “A” in 1956, she became more personal: “I have never been anywhere, but sick. In a sense, sickness is a place, much more instructive than a long time to Europe, and it’s always a place where there’s no company, where nobody can follow. Sickness before death is a very appropriate thing, and I think those who don’t have a miss one of God’s mercies.”

As O’Connor knew only too well, the medications she took only controlled (they did not cure) her lupus. She accepted the incurable nature of the disease as inevitable, though naturally undesirable.

In the fall of 1951, after spending nine months in a hospital, she returned to Milledgeville. Because she could not climb the stairs, her mother brought her to their country home, Andalusia, which is located about five miles from town. Flannery O’Connor had no need to climb there. She lived at Andalusia for the next 13 months, before dying.

Her mother was the widowed mother of an only child whose physical health was her single-minded concern. She would not be alive, Flannery O’Connor once commented, but for her mother’s care. The writer professed great love and gratitude for her mother.

Outside the house, everything clucked and gamboled with life: ducks, geese, turkeys, pheasants, swans and chickens of every description. Her uncle, Louis Cline, kept her supplied with feathery exotica, including peacocks. When Andalusia was in the bloom of life, these kings and their queens roamed everywhere, choosing their roosts, fencepost and branch of the surrounding trees. To a visitor, O’Connor once pointed out that the peacock was, in medieval times, considered to be a symbol of the Transfiguration of Jesus.

O’Connor was an unappreciated prophet in her home town. A physician who worked in the local mental hospital had read her novel Wise Blood. He once commented: “I enjoyed it, but I know one thing for sure. She don’t know a damn thing about a whorehouse.” Flannery later admitted she had leaned on conjecture in her Wise Blood brothel episode.

She was jovially critical of the Irishness of the Milledgeville Irish-American pastor, the way he draped the church in green on St. Patrick’s Day. She was less jovial in her criticism of what she called the Irish cast of American Catholicism of her time.

The only activity that took O’Connor away from Milledgeville during the last decade of her life was her lecturing and reading from her work in colleges. She never gave the same lecture twice; she always worked over her notes, adding here and subtracting there.

Ralph McGill, a columnist who was known as “the conscience of Atlanta,” was proud of Flannery O’Connor and knew her life history in great detail. He once quoted Atlanta novelist Margaret Long as saying: “Flannery certainly is a great writer, but, you know, there is no love in her writing.”

When confronted with this statement, O’Connor said: “She’s right. You can’t write about love when you haven’t had it, leastwise the kind she is talking about. I never had any.”

She, in fact, never did. The early onset of her dreadful illness ruled out the normal activities of youth that lead to love and marriage. She was incapable of being anything but herself, and the self she was would probably have frightened away any save a suitor of singular discernment.

She was not, however, without offers. A letter once came to her from a young man in Florida. In effect, he said: “It is evident that you know nothing about sex. I know plenty about it, but I don’t write very well. What say we pool our skills?”

Her Ideas and Her Writing

Fiction, Flannery O’Connor observed more than once, is not a statement or a sermon or anything other than dramatic action presented through specific details that a reader can apprehend through his or her own sense. That is not to say her works lacks imagination. Hers is what she called “an incarnational art”; it reveals spirit through mater and embodies truth.

Central to O’Connor’s life and writing was her Christian faith. It was rigorous and unsentimental. “I take the Dogmas of the Church literally,” she wrote in one letter. “Dogma,” O’Connor said, “is the guardian of mystery. The doctrines are spiritually significant in ways that we cannot fathom.”

“O’Connor recognized that many persons viewed Catholicism as being restrictive to her life as a writer. From her perspective, however, faith was essential and liberating, freeing her to write. “For fiction writer,” she argued, “to believe nothing is to see nothing. [However], I don’t write to bring anybody a message; as you yourself know, this is not the purpose of the novelist.”

While, she believed in all the mysteries of her faith, she was incapable of writing dogmatic stories. No religious tracts, nothing haloed by celestial light, nor happy endings. It has puzzled some of her readers and annoyed the Catholic Church that, in her stories, not only does good in triumph, it is usually not present. Seldom are the choices, and God never intervenes to help anyone triumph.

To O’Connor, Jesus won only by losing. She believed that not much has been learned by his death, and that it is only by His repeated dying-touching one’s life in a direct way-the meaning that original loss has been pressed into the heart of individuals.

“Don’t think that you have to abandon reason to be a Christian,” she wrote in one letter. O’Connor argued that the Christian faith provides a person a place from which to critique the world views to which one is exposed in college. “Don’t look for final answers, but for different questions. What kept me a skeptic in college,” she wrote, “was precisely my Christian faith. It always said wait, don’t bite on this, get a wider picture, continue to read.”

Unapologetically Roman Catholic, O’Connor was not provincial in matters of faith. She fought against being cast in the role of apologist for the church in her fiction. To novelist friend John Hawkes, she wrote: “People are always asking me if I am a Catholic writer. I am afraid that I sometimes say no, and sometimes say yes, depending on who the questioner is.”

While O’Connor kept informed about theological issues, in the early days of Vatican II, she valued strictness with herself in matters having to do with church discipline. While others were leaving the church in protest of its strictures, O’Connor maintained that she drew her strength from the church’s firm guidelines.

We are, she believed, creatures shaped almost entirely by our choices, which is to say, by ourselves. We remain essentially responsible beings before God for whatever we do. Those changes wrought in us by what we do, whether for good or ill, can best be understood in light of what some people call character.

In all of her writing, O’Connor moral tone is neutral, whether she presents an amoral murdering redneck, a devouring middle class mother, or selfish Catholic girl. In O’Connor’s world, all humans are predestined misfits or freaks. The victim and the freak serve as a reminder that persons are weak and yet have a capacity for the infinite. Every person has limitations; yet, even this imperfect life, she argues, “has for all its horrors, been found by God to be worth dying for.” If so God regards humanity, then each person is worth another person’s consideration.

O’Connor populated her stories with grotesque characters. She once commented “To recognize the grotesque, you have to have some notion of what is not grotesque, and why.” Her use of the grotesque in her characters was to probe the distinction.

Her grotesquerie is full of people who are “good” religious and moral characters but who have somehow managed to distort goodness into the unnatural. They emerge as distorted images of the good. O’Connor’s purpose in telling stories about such people is to tell the truth as the artist sees it-and to tell it with sufficient force that the “point” of the story is unmistakable.

Having grown accustomed to the hard words of the gospel, religiously-minded folk slip easily into conventional religious observance. It is a writer’s obligation to shock people who have grown accustomed to religious speech. O’Connor wrote: “To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and starling figures.”

For Flannery O’Connor, writing and faith are tightly bound together. She identified “conversion”-that is, “a character’s changing”-as the only real subject of good literature.

What created story for her, what created the necessary conflict, was a character’s resistance to God’s grace, which often led violently to sudden revelation.

In O’Connor’s stories, as much as we hope for a happy family, an integrated person in body and character, we are repeatedly disappointed. If we do not necessarily demand that stories have “happy ending,” we do expect the ending to flow in good order from previous incidents. Time after time, O’Connor’s stories end in some act of violence. The endings bring a revulsion, a turning around, that is but a foreshadowing of conversion, the radical turning away from egotism to God.

In Wise Blood, her first novel, O’Connor’s Hazel Motes attempts to establish “the Church without Christ” in a dilapidated automobile that ends up covered with kudzu in a Georgia pasture.

Quoting from the Book of Matthew (11:12), she entitled her second novel The Violent Bear It Away. Like a peacocks beauty, which requires violent shaking to produce, the Kingdom of Heaven comes for many persons only after they have been badly shaken. The character Tarwater was one of those; once shaken up, he set out to do likewise.

In one of O’Connor’s most famous short stories “A Good Man is Hard to Find,: a daffy old matron leads her entire family to destruction at the hands of “the Misfit,” a cold-blooded killer, who blames his troubles on Jesus Christ and defines pleasure solely in terms of the harm he can inflict on others. When, in the course of trying to save her own life, the old lady stops urging him to seek Jesus and tries to embrace him as one of her own children, he shoots he at point-blank range and offers a fitting inscription for her tombstone, observing that “she would be a good woman, if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” O’Connor’s letters, entitled The Habit of Being (Vintage, 1979), bring into focus the human being behind the art. The O’Connor family did not install a telephone at their farm until late in Flannery’s life, so to communicate with her friends, she had to write to the. These letters from a diary beginning in 1948, after her graduation from the University of Iowa, until her death in 1964. Of particular interest are her views on the business of writing-a business that was for her indistinguishable from the spiritual life itself. On August 2, 1955, she wrote: “One of the awful things about writing when you are a Christian is that for you the ultimate reality is the Incarnation, the present reality is the Incarnation, and nobody in your audience. My audience are the people who think God is dead. At least these are the people I am conscious of writing for.”

Her letters reveal a keen awareness of the absurd and an appreciation of the caprices of human personality. Whether describing the farm help, her neighbors, or visitors to Andalusia, O’Connor demonstrated an ability to spot the comic in human affairs.

She told, for example, of a man who telephoned and announced: “I have written as novel,” and asked if he could visit with her and discuss publication possibilities. Though O’Connor had “never heard of him, but that is not unusual,” she consented. He turned out to be “87 years old with a wife about 40 who calls him ‘sweetheart’. He is writing a book about ‘a modern woman’. My mother asked what was a modern woman. ‘One without scruples,’ he says”

O’Connor knew the difference between art and religion, and never confused the two subjects. She understood that her primary duty was to tell an engaging story.

What To See and Do

“Amen, Amen!” an old woman once cried when a Flannery O’Connor peacock displayed its grandeur. It is a fitting response to her stories. O’Connor left behind more than three dozen short stories, two novels and a dozen essays. She told stories that no one else had ever told, profoundly comic stories, often radically conservative in their implications, shocking, disturbing and serious, as only comedy can be.

In the twilight of spring, with jonquils and sweet olive perfuming the air, it is not hard to imagine Milledgeville as Flannery O’Connor saw it. To visit here today is to tread in the footsteps of a remarkable and sadly missed literary figure.

The city has Georgia’s best-preserved display of Federal-style architecture, enhanced by Greek Revival, Classic Revival and Victorian houses abiding side-by-side throughout the historic district. Milledgeville’s starchy traditionalism and its lode of Southern Gothic paradoxes were the perfect foils for Flannery O’Connor’s surgical Irish Catholic wit. It remains a popular pastime, a third of the century after her death, for townsfolk to scan her books, trying to determine who among them were models for Francis Marion Tarwater, Rayber, the Greenleafs, Hazel Motes and assorted other rascals, revivalists backwoods meanies, freaks and patient sufferers who roam her novels and short-story anthologies.

Memory Hill is the 30-acre cemetery designed in 1804 as part of the original town-the second-oldest planned cemetery in the state of Georgia. Flannery O’Connor is buried there, only a few blocks from the 1820s house where her family lived.

Furnishings from the writer’s home and manuscripts are on display in Georgia College’s Ina Dillard Russell Library in Milledgeville. Scholars and O’Connor fans come each year to view photographs of Flannery O’Connor as a child, first editions of her books, her personal library and mementos. The library is open Mondays through Fridays 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. The telephone number is 912-445-4047.

Northwest of Milledgeville on Highway 441, you will come to a sign on the left that says “Andalusia.” The O’Connor home is a large white abode that has a view of a lake from its screened-in front porch. Andalusia is not open to the public. ♦

Leave a Reply