Rosemary Rogers, continuing her series on Irish women of note, profiles Constance Georgine Gore-Booth, the social agitator and revolutionary who took part in the Easter Rising of 1916.

Revolutionaries are, almost by definition, romantic – what else could explain the fact that the iconic image of Che Guevara (whose Grandma Lynch, incidentally, was from Galway’s Lynch tribe) is still ubiquitous 50 years after his death? Countess Markievicz, the fierce and courageous Irish revolutionary at the heart of the 1916 Easter Rising, cultivated her romantic image by fusing her flair for theatrics with her great heart and earned forever a place in Ireland’s history and imagination.

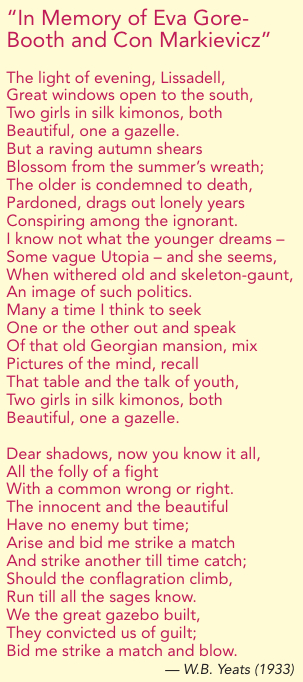

Constance Georgine Gore-Booth was born into County Sligo aristocracy, married into Polish nobility (hence the “Countess”), and as a young girl in Lissadell, her family’s estate, she was immortalized in poetry by her Sligo neighbor, W.B. Yeats. He admired her beauty, “lonely wildness” and likened her to a gazelle. Indeed she was always in mad motion, a comet whose life followed an astounding trajectory: in 1887, she was presented before Queen Victoria as “the new Irish beauty” but, within 29 years, she was sitting in Kilmainham Jail, under a death sentence for participating “in an armed rebellion against His Majesty the King.”

At the turn of the century Count and Countess Markievicz were at the center of Dublin’s artistic set and fixtures in society gatherings at Dublin Castle. Before they even arrived in Ireland, the publisher A.E. Russell enthused, “The Gore-Booth girl who married the Polish Count with the un-spellable name…will help create an art atmosphere.” He was right. The Countess was a talented landscape artist and the Count, though penniless, was a handsome writer and one of the few men around who was taller than his very tall wife. He wrote and staged plays in which she starred, and the artsy-but-elegant couple settled into a Georgian mansion with their daughter Maeve and the Count’s son by his late wife.

In 1906, the Countess took a solitary painting retreat in a cabin in the countryside. It was there that she had what could only be called an epiphany. She discovered some Irish revolutionary literature left by a former tenant, the poet Padraic Colum. Instead of painting, the Countess read and kept reading with increasing passion. To borrow again from Yeats, she had “changed, changed utterly” and returned to Dublin a rebel dedicated to Ireland’s freedom. She joined Sinn Féin and founded Fianna Éireann, a youth movement.

The Countess, who had an amazing talent for re-inventing herself, turned social agitator, joining forces with union leader “Big Jim” Larkin and James Connolly in The Lockout of 1913, the labor strike which led to the creation of the Irish Citizen Army. She, so often accused of haughtiness, ran soup kitchens and personally delivered food and medicine to the strikers’ families and other starving Dubliners who she saw as the “dispossessed people of the old Gaelic race.”

It was her relationship with James Connolly, the scrappy and brilliant socialist from the slums, that proved the most significant of her life. He was her mentor and Madame, as she was now known, was his protector, providing him with a home (and a bodyguard) while he stayed in Dublin. When World War I broke out, both were active in the Irish Neutrality League – not only were Irishmen volunteering to fight for the Empire that had enslaved them but there was danger that the British government would, at any time, impose conscription. It also meant that the long-delayed Home Rule for Ireland bill would be put on hold once again. During a rally at Liberty Hall Dublin, Connolly denounced the war as the work of “a small clique of rulers and armament workers.” He took one side of a tremendous banner, “We Serve Neither King Nor Kaiser But Ireland,” the Countess took the other – they unfurled it and a photograph was taken that went around the world.

In 1916, Connolly, commandant-general of the Easter Rising, co-signer and co-architect of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, Poblacht Na hÉireann, appointed the Countess as Lieutenant and second-in-command of the rebel position at St. Stephen’s Green. On the morning of Easter Monday, Madame marched through gas-lit Dublin streets at the head of a column of the Citizen Army. She was wearing her dark green uniform, a slouch hat with a pin of the Red Hand badge of Labour and riding breeches covered with a long dress. She carried a rifle and the Mauser automatic she had dubbed “Peter the Great.”

During the fighting, word spread of her fearlessness (and recklessness). When it was all over and the rebels had surrendered, she wanted to continue the fight but reluctantly followed orders to cease firing. She turned her gun over to the arresting officer who, in a typical twist of inbred Irish politics, just happened to be one of her cousins. At her court-martial, Madame announced, “I did what was right and stand by it,” and was sentenced to death by firing squad. When her sentence was reduced (“because of her sex”) to penal servitude for life she was both insulted and infuriated, huffing, “I do wish your lot had the decency to shoot me.” It was during the Rising, in the heat of battle, that the Countess had yet another epiphany. Seeing the faith of the rebels, hearing the zen droning of the rosary, she decided to convert to Catholicism, which she did soon after being released in the General Amnesty of 1917.

And where were her husband and daughter during all of this? The Count had moved to the Balkans to work as a war correspondent and Maeve was off in Sligo to live with her grandparents at Lissadell. The Countess always remained close with her husband, less so with her daughter. Maeve spent her childhood in Ireland but had the “misfortune” to be at an English boarding school in 1916 where she earned notoriety as “the Rebel’s Daughter.”

In 1919, Madame was sentenced again, this time for sedition; while in Britain’s Holloway Prison, she ran for a seat in Parliament. The Irishwoman with the Polish name won and became the first woman ever elected to the British Parliament. In accordance with Sinn Féin, she refused to take an oath of allegiance to the King and when the other Irish M.P.s voted to form the Dáil Éireann she cast her vote as fé ghlas ag Gallaibh (“imprisoned abroad”).

Released in 1919, she became the Minister of Labor of the first Dáil Éireann, the only woman in the world (saving another in USSR government) who sat in a government cabinet. In 1922, she joined forces with Eamon de Valera in opposing Michael Collins’s Anglo-Irish Treaty (all three were veterans of the 1916 rising) and supported the Republican cause in the Irish Civil War, taking up arms against the Free State Government.

The fierce progressive had, sadly, become isolated from the other feminists of her generation since they concentrated on suffrage and pacifism while her focus was revolution and warfare. Madame Markievicz may have backed the wrong man in de Valera. The Free State government gave women the vote in 1922, while de Valera – in office, in one way or another, from 1927 to 1973 – engendered a culture that was Catholic Church-centric, reactionary, and oppressive toward women and their rights.

Before her death in 1927, she was once more imprisoned and elected to office. She gave away all her possessions to the poor of Dublin and died penniless in charity ward, possibly from tuberculosis. Her husband (who had from 1913 lived in Ukraine, but the two corresponded always) arrived for a deathbed visit that Constance described as the happiest day of her life. She was 59 years old. ♦

An excellent educational article. It deserves perusal and cogitation from readers who are interested in Irish history. I called a friend after reading this and implored him to become a reader/member of the Irish America Magazine. Even for individuals like this writer who are familiar with the background of Constance Georgine Gore-Booth, it’s still very entertaining.