A Window on the Past: Historian Christine Kinealy debunks the myth that Ulster was untouched by the Great Hunger.

The myth of Ulster exceptionalism and affluence has roots in the Great Hunger itself. As early as 1849, Protestant loyalists were laying the foundation for a binary, two-nation view of the Famine. Objecting to a new tax that was to be levied on all parts of Ireland, the Belfast Newsletter claimed: “This is not the way to secure the affections, or reward the loyalty, of the sturdy men of the North, who, proud that they have been able to feed their own poor, and even to give of their abundance, in times of need, to the poor of distant provinces, will now be compelled to feed the starving masses in whom bad landlordism, disloyal teaching, a false religion, and an inherent laziness have combined to render at once the shame and the canker of their country.”

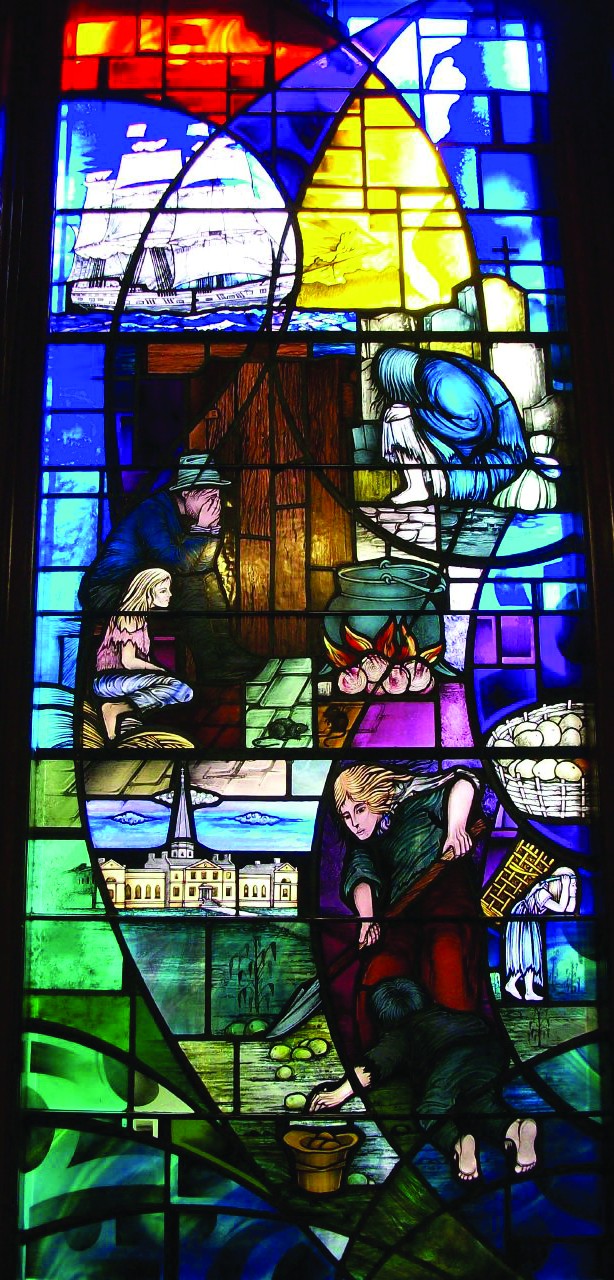

Later generations of unionists built on this fissured – and sectarian – division of the country. As late as 1996, during debates in Belfast City Hall about erecting a famine memorial in the city, Sammy Wilson, a Democratic Unionist councilor, objected on the grounds that “There is no evidence that the Famine played any part in the history of Belfast.” Despite Unionist objections (with the honorable exception of the Progressive Unionist Party) a beautiful stained glass window was eventually installed in the City Hall, although relatively few people – including Belfast residents – know of its existence.

So what was the impact of the Great Hunger on the north?

The towns of Belfast, Lurgan and Ballymena, which were part of the prosperous “linen triangle,” all suffered severely. Workers in the local linen mills traditionally ate potatoes, so the blight deprived them of their usual foodstuff. Moreover, the potato failure coincided with an industrial downswing, leaving thousands unemployed. Government relief in the north proved to be no more efficient than relief in the south in coping with the crisis. By February 1847, for example, mortality in the Lurgan workhouse equaled levels in the most impoverished workhouses in County Cork.

In the predominantly Protestant district of Ballymacarrett in Belfast, privately funded soup kitchens had been operating since 1846. By 1847, 12,000 people were receiving food rations from these establishments every day, representing more than 60 percent of the population. The distress was so severe that Ballymacarrett was likened to Skibbereen, a small town in west Cork, that had become the unwitting barometer of extreme suffering – and that suffering was being replicated in all parts of Ireland.

Mortality was so great in Belfast that the town’s cemeteries were overflowing with dead bodies. Dr. Drew, a leading Anglican clergyman, described their condition as “shameful to any Christian community.” Moreover, the usual rites of burial were no longer being observed. Following a visit to the Shankill cemetery – then and now located in the heartland of Protestant Belfast – Dr. Drew wrote: “A few days since I turned away in disgust when I observed the manner in which the bones and skulls were thrown up and about and in which the spade was stuck into the coffins and dead bodies which had seemingly been but a short time deposited.”

In July 1847, relief provided by the government peaked, with more than three million people receiving free rations of soup every day. For Orangemen, this was the month of their annual Twelfth of July processions. The Belfast Chronicle chastised the Orange Order for wanting to march as usual, pointing out:

“… in every town and village and cluster of cottages, death is busy with his victims, and shall we hear, as though in wilful mockery of these solemn judgments, the air ringing with merry music, and the voice of triumph and jubilee, when thousands of our fellow-creatures are perishing of disease and want?”

The Rev. Hartley Hodson, chaplain to the Orange Order, also urged restraint, asking:

“How many, alas, of your flags have but too recently enwrapped the dead? Suffer then the days of their mourning to be ended before you drag them forth to help in an untimely mirth. What one of your lodges is unbroken by death, unstricken by disease, unreached by affliction? Nay, where is the house that has escaped?”

The local Orange lodges decided that the processions should go ahead, but acknowledged the suffering of their community by agreeing that no music would be played.

Statistics of mortality and emigration are often used as indicators of suffering during the Great Hunger. While they cannot convey the cultural or psychological loss endured by the Irish people, they provide a crude measure of the enormity of the tragedy. The 1851 census records a population loss of 16 percent for the province of Ulster, while Connacht and Munster lost 20 percent, and Leinster, 15 percent. Clearly, no part of Ireland and no tradition was untouched by the Great Hunger. ♦

_______________

Professor Christine Kinealy is Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University. She is author (with Gerard McAtasney) of The Hidden Famine: Hunger, Poverty and Sectarianism in Belfast (Pluto Press, 2000), and an editor of Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization (Quinnipiac University Press, 2015).

One of the largest attenuating circumstances of the famine in the North was the fact that tenants were paid for their leasehold improvements. This practice was known as “tenant right”. Tenants were compensated for any improvements made to their holdings. ‘The Great Hunger:Ireland’ states that “the superior prosperity and tranquility of Ulster, compared with the rest of Ireland, were due to tenant right.”