Hillary Rodham Clinton’s role in the Irish peace process is often underestimated but there were few people more important.

In retrospect it all seems so obvious. Once an American president focused on Ireland, there would be an immediate concerted effort to find a way to end Europe’s long-running war.

After decades of war the American intervention was decisive, a fact admitted years later by the British government themselves. The reality at the time was different, however. When President Bill Clinton became the first U.S. president in history to focus on peace in Ireland, the initiative was opposed on all sides.

The British government was apoplectic that a foreign power would meddle in its backyard, and Prime Minister John Major told President Clinton so.

In his own administration, the FBI, State Department, Justice Department and the CIA fought tooth and nail to keep the president out of efforts to sort out the conflict.

They were aghast when the decision was made to allow Gerry Adams, the Sinn Féin leader, a visa to come to America in late January 1994.

Yet Clinton persisted. One of his key advisors in his decision was his wife, Hillary, who saw the potential for peace in Ireland.

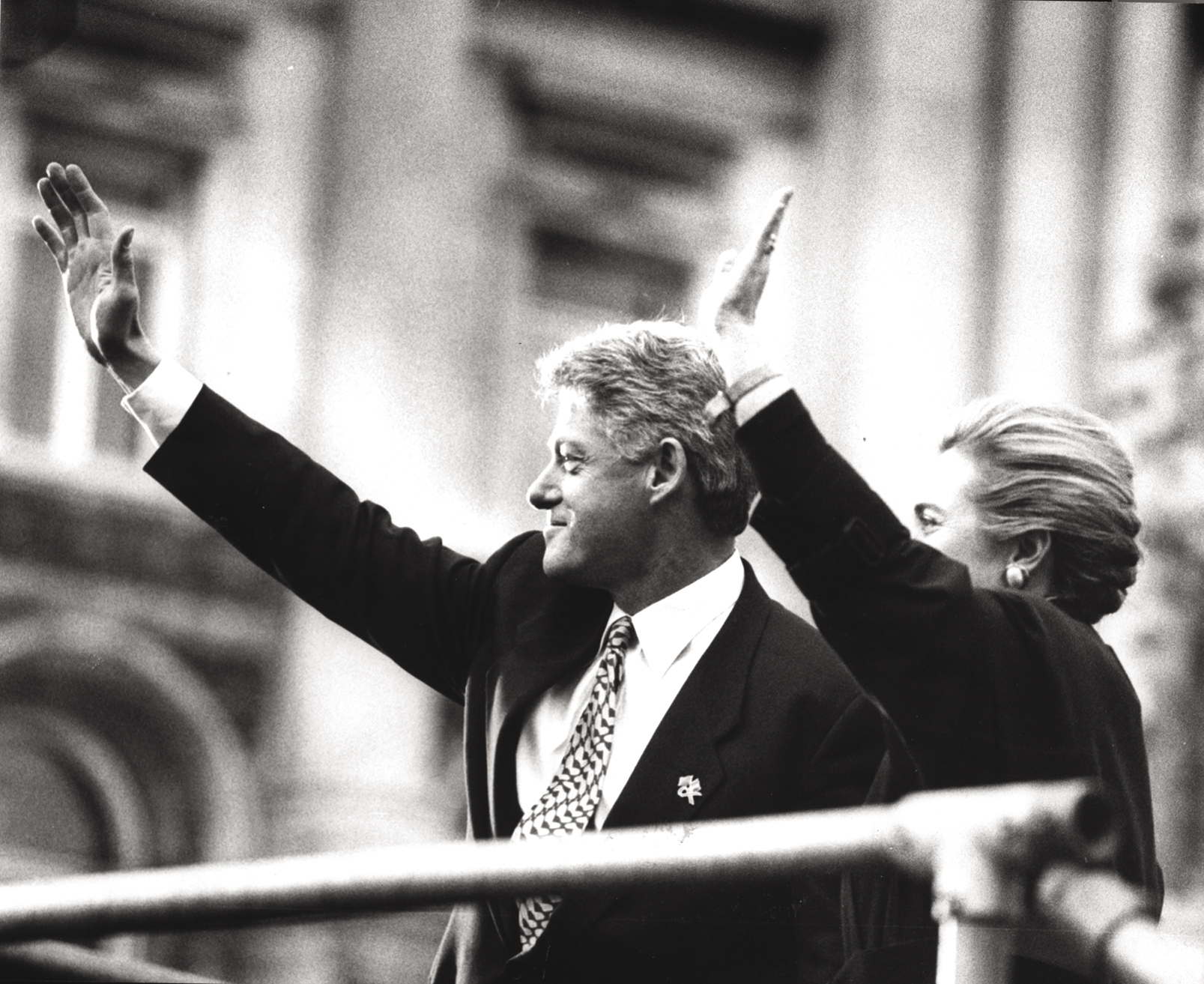

Not only that, Hillary determined that she would become part of it. She accompanied her husband on what has been described as “the two best days of his presidency” by Terry McAuliffe, their chief fund-raiser, who accompanied them to Ireland in November 1995 and watched them bask in the warm glow of appreciation as hundreds of thousands of people in Belfast and Derry came out to welcome the U.S.

President and First Lady who had helped bring peace to Northern Ireland.

In his memoir What a Party!, McAuliffe, now the governor of Virginia, remembers that visit as the high point of the Clintons’ White House years.

During that trip and subsequently, Hillary Clinton played a leading role in creating the links between the White House and leaders on the ground that would be so important in subsequent years.

Her visits to the Falls and Shankill Roads in Belfast to meet working-class women from both communities were especially important. She helped empower key women at a time in the conflict when women’s voices were hardly heard. She played a major role in setting the groundwork for the formation of parties such as the Women’s Coalition, which was to play an essential role in cross-community bridge building in the vital years when the peace process was being bedded down.

On her first visit to Northern Ireland in 1995 she made the acquaintance of Joyce McCartan, an extraordinary Protestant woman married to a Catholic, whose own son had been killed in the Troubles.

As her biography noted, McCartan lost 17 members of her wider family during the Troubles including, in May 1987, her youngest son, Gary, who at age 17 was murdered in the family home by loyalist paramilitaries. McCartan herself heard the shots.

The incredible personal tragedy fueled McCartan’s desire to find a way to stop the violence. She founded The Lamplighter drop-in center, which became a guiding light amid the encircling gloom for families weary or fearful of the Troubles who wanted to talk and mingle.

In November 1995, McCartan, the center, and its Lamplighter Cafe, were in the world’s spotlight when First Lady Hillary Clinton dropped in for tea and a chat with a group of women from varying backgrounds.

Hillary later described how after the chat and tea, McCartan “gave me an old battered aluminum teapot – which kept the tea very warm, which is what I first noticed about it – that I took with me to the White House where I used it every single day in the second-floor private kitchen.”

The teapot story was often subsequently referenced by Hillary. She established the Vital Voices initiative in the North, which brought mostly, but not exclusively, women at community level together and provided a powerful forum for groups with little or no voice.

It cannot be underestimated just how few women were in any positions of power in the North back then, and Hillary went about changing that from the grassroots up.

As she stated in 1999, Vital Voices was “certainly part of a larger effort that I have been privileged to view firsthand, since my husband and I first came in 1995. And that is the way that the people here have pulled together to make peace real in our lives and in our time.”

Inez McCormack, the late beloved trade union organizer and human rights activist community worker, told me in a Belfast restaurant that Hillary had single-handedly empowered women in the Northern Ireland conflict, which had a profound impact.

McCormack quoted to me her own definition of success: “When I see a glint in a woman’s eye who believed she was nobody and now knows she is somebody.”

Hillary, she said, led the way for Northern Irish women to see that breakthrough.

Then, of course, there were the meetings in Washington, usually around St. Patrick’s Day, and the White House “Irish night,” which became a fixture at Hillary’s insistence.

The boost to the peace process of a First Lady of the United States welcoming party leaders of whatever stripe to the White House had to be seen in person to be believed.

When perhaps the most famous woman in the world spent an extraordinary amount of time just listening to the perspectives from the various parties, it was bound to have an impact.

Progressive Unionist Party Leader David Ervine, tragically now deceased, described her as the most knowledgeable person on the issue he had met in Washington. John Hume, the SDLP leader and Nobel Peace laureate who was a frequent visitor and friend, agreed. They were sitting together in a smoky hotel bar in Washington, D.C. after an economic conference on Northern Ireland, another Clinton initiative, and Hillary had just knocked them dead with a spirited contribution on peace and economic strategy.

It is an intricate business, learning the details of Northern Ireland politics so that you never put a foot wrong. Yet, amazingly, with everything that was pressing on them, neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton ever made the kind of slip-up that would have led to embarrassing headlines on the issue.

I remember sitting down with them for a brief interview in the ambassador’s residence in Dublin on one of the trips over. It was clear they had both become enamored of the Irish, and were gratified to have helped solve the riddle that was Northern Ireland in a way that had surprised even themselves.

Hillary used the example of her peace efforts in Northern Ireland on her future global travels. Soon after being named Secretary of State she met with a small group of Irish-American leaders and spoke of her hopes that Irish Americans would meet and give advice to other diaspora leaders such as Pakistani and Indian Americans, revealing to them how the Irish diaspora helped end the conflict in Northern Ireland.

As Secretary of State, Hillary convened several diaspora conferences and used Ireland as an example of peace brokering in her bestselling memoir, Hard Choices. She also included Northern Ireland on her final travel trip as Secretary of State and received an overwhelming reception from party leaders on all sides when she spoke at a luncheon sponsored by the American Ireland Fund at the Titanic Quarter in Belfast. She promised to stay involved and she has.

Hillary, who has made history in so many ways, has also helped make it for the Irish. Most importantly, the Irish know she walked that long and tortuous road with them to help bring peace and that she will be there for the last mile. ♦

Hillery will be our President when Irelanld gains their freedom.

Peace for 2016