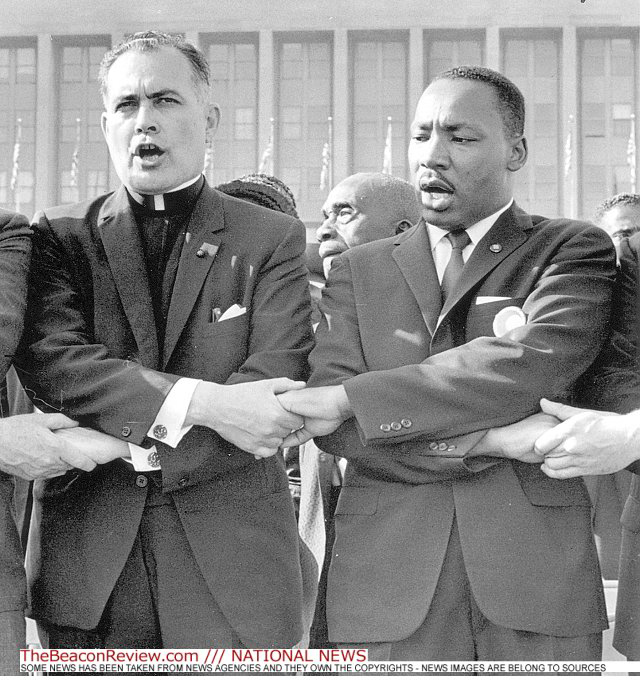

Reverend Theodore Hesburgh

1917 – 2015

A former president of the University of Notre Dame and one of the most public Catholic leaders in the 20th century who fought for civil rights and university autonomy, often at odds with both the Vatican and U.S. presidency, died late February. Reverend Theodore Hesburgh died at his home at the Holy Cross seminary on the Notre Dame campus in South Bend, Indiana, having attended daily mass and keeping office hours until the week before his death. He was 97.

Father Hesburgh never wanted an administrative role at the university, where he took his vows in 1943 at the age of 26, initially hoping to serve in the U.S. Navy as a chaplain on an aircraft carrier and later simply to teach. But he was assigned to Notre Dame during the war to help train naval officers and was made president just nine years later, at 35, after serving as vice president and assistant to the president.

When he retired in 1987, he was the longest-serving Notre Dame president in history, having overseen a number of key transitions for the university and the nation. That same year, Father Hesburgh was named the most effective college president in the U.S. by a survey of 485 university presidents. He had audiences with presidents and at the Vatican, but rejected the idea that either the national government or Rome should have greater control over the university than the administration and the board.

“[He] took Notre Dame from being a rather small Catholic Midwestern institution to being an … academically distinguished institution,” Rev. John Jenkins, Notre Dame’s current president, said in an interview with NPR.

At Notre Dame, Father Hesburgh doubled enrollment, oversaw the admission of the first women in 1972, increased the university’s endowment from $9 million to $350, and transitioned control of the university from the Congregation of the Holy Cross to a primarily secular board. But he was also a national figure in business and politics, serving on several boards of directors for various organizations, including Chase Manhattan Bank and the U.S. Institute of Peace, and more than a dozen presidential commissions, including the Commission on Civil Rights for 15 years, the last five of which he served as chairman until his criticism of President Nixon led to his forced resignation in 1972.

“It’s important to remember, this is the ’60s,” Rev. Jenkins emphasized with NPR. “It was not universally acclaimed… for a Catholic priest to be advocating for civil rights for African-Americans. It was the middle of the Cold War; it was not universally accepted to argue for nuclear disarmament. He was a courageous leader for this time, and for that reason a highly influential one.”

Indeed, even into the 1990s the Vatican was still dealing with the fallout from the Land O’Lakes Statement, released by a group of Catholic academics assembled by Father Hesburgh in 1967, which began: “To perform its teaching and research functions effectively the Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.” It was a shot across the bow of St. Peter’s.

The Vatican released its own statement on the role of Rome in Catholic universities in 1990, the Ex Corde Ecclesiae, which outlined requirements for Vatican-sanctioned Catholic institutes of higher education.The president emeritus of the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars told the Catholic World Report that when asked about Notre Dame’s compliance with the document, Father Hesburgh reportedly said, “What is the worst thing that can happen to us? John Paul II will tell the world that Notre Dame is not a Catholic university. Who will believe him?” A decade later, Notre Dame’s faculty senate voted unanimously to ignore the Ex Corde Ecclesiae.

Theodore Martin Hesburgh was born in Syracuse, New York in 1917. One of five children of Theodore Bernard Hesburgh and Anne Murphy, he said he had wanted to be a priest since the age of six, and had wanted to attend Notre Dame since eighth grade, when four Holy Cross missionaries came to his parish church and sold him on the seminary in South Bend. In 2010, President Bill Clinton awarded Father Hesburgh the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor in the U.S. He was the first person from higher education to be awarded the medal. At a 2013 birthday celebration in Washington, D.C., vice-president Joe Biden called Hesburgh “the most powerful unelected official this nation has ever seen.”

“In his historic service to the nation, the church and the world,” Rev. Jenkins said in a statement, “he was a steadfast champion for human rights, the cause of peace and care for the poor.”

– Adam Farley

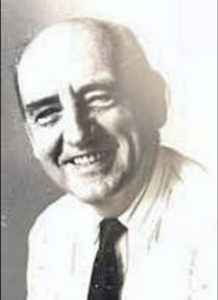

D. Michael Collins

1944 – 2015

Toledo Mayor D. Michael Collins, a first-generation Irish American who had led a life devoted to civil service, died in February following a cardiac arrest. Collins, an independent, was elected mayor in 2013 and was just beginning his second year in office. He was 70, and the first mayor of Toledo to die in office since 1904. Prior to his mayoral bid, Collins had served as a city councilman since 2007, and prior to that worked as a detective with the Toledo Police Department, where he also headed the Toledo Police Patrolman’s Association for more than a decade.

Collins was born in 1944 to Michael John Collins, who immigrated to Toledo from Ireland, and Gertrude Helmer, whose ancestors came from Germany. But it was his Ireland connections that Collins relied on for his public service, maintaining close ties to his relatives still in Ireland, and even implementing Ireland’s “Tidy Towns” program to clean up Toledo.

Former Toledo Mayor Carty Finkbeiner told The Toledo Blaze, “We should celebrate Mike’s commitment to improving the quality of life for Toledoans and their families and policemen and their families.”

“He was a true old-fashion Irish leader. He would be urging us to continue on to do those things to make Toledo better… Intense, and at times combative, and a competitor. He had a warm Irish heart beneath the intense, combative exterior.”

Collins is survived by a sister, Mary Pat Hobbs, his second wife, Sandra Drabik, and three daughters from a previous marriage, Tammy Dickey, Laurie Mulligan, and Kelly Sheridan.

– Adam Farley

Sean Corrigan

1917 – 2015

Irishman Sean Corrigan, 42, of Medfield, Mass. died while inspecting snow removal on a warehouse roof, falling through the skylight. The Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency reported over 140 building and roof collapses in February.

Corrigan was originally from Co. Mayo and had been living in Boston for a number of years with his wife Sheila. He returned to Ireland often throughout the years, maintaining contact with family members on both sides of the ocean. Following Sean’s death, a memorial service was held at Gormley’s in Westport, Roxbury. His body will be laid to rest back home in Mayo. The Corrigan Family Memorial Fund was set up in Sean’s honor to support his wife and their three children at giveforward.com. So far nearly $80,000 of it’s $125,000 goal has been reached.

– Matthew Skwiat

Michael Lambert

1907 – 2015

Michael Lambert, former holder of the title “Ireland’s Oldest Man,” has died. He was 107. He was born in Clooneygrasson, Castlerea, Co. Roscommon on October 5, 1907. Throughout the span of his 107 years, Lambert witnessed a complete transformation of Ireland, but remained committed to his Roscommon roots.

He was born, according to his son Edward in The Irish Times, “in a thatched cottage beside what is now the family home.” Lambert’s was an active life filled with hard work and his love of family. He married late, to Mae Collins who lived in a nearby village. The two were married for more than 60 years and produced 10 children with a total of 22 grandchildren.

His early life was like something out of a novel, leaving school at 12 after his father died, taking over the family farm, and eventually settling down in his 40s. Lambert left Ireland only five times during his lifetime, even though he had a U.S. passport. He used to visit his mother who moved to America soon after his own marriage. He credited his long life to quitting smoking 60 years ago and to good ol’ family genes (both his sisters lived well into their 90s). His son gives credence to the old mantra, slow and steady wins the race, saying “he was a placid, easy-going man. He said his prayers at a slow pace, he ate his dinner at a slow pace, he never rushed anything.”

While Lambert was the oldest man in Ireland, the oldest Irish person honor goes to Kathleen Snavely in Syracuse, NY, who turned 113 in February.

– Matthew Skwiat

Sean McCann

1930 – 2015

Sean McCann, the prolific author of more than 25 books, a former Evening Press journalist, and the father of award-winning Irish author Colum McCann, has passed away. He was 85. Born in Dublin, he moved to London with hopes of becoming a football star (a dream young Colum also inherited), playing for the Charlton Athletic. By the early 1960s he settled down and returned to Ireland and took up journalism.

It was from his father that Colum was introduced to the world of literature, who describes in “The Word Shed,” published in The New Yorker last December, his world of literary creation as “The ping of the bell. The slam of the carriage return. It all sounded like a faint form of applause.”

Sean had a successful career at the Evening Press, running a weekly column called the “Petticoat Panel” and hiring a number of prominent writers including Claire Boylan, Noeleen Dowling, and Liam O Cuanaigh. John Boland, writing in The Irish Independent, called him “a civilised and unfailingly charming journalist of the old school.” Sean published works on Irish wit and children’s books centering around the soccer-playing underdog Georgie Goodie. When not writing stories, McCann was an avid gardener, which landed him several international prizes.

Sean McCann is survived by his wife Sally and his five children.

– Matthew Skwiat

Leave a Reply