Five years after the tragic loss of their mother and sister, the five Murray daughters and their father, Sean, continue to thrive.

Tie-dyed sheets line the back of a Chevy Chase classroom where a group of preteen girls sit discussing some of the weightier topics of adolescent life: Why do we feel the need to conform? Is it harder to stick up for ourselves or for someone else? What does it really mean to be beautiful?

“I said that it means if you have a good personality,” volunteers Maeve Murray, a freckle-faced 11-year-old with auburn hair. “It’s not about what you look like or how you dress.”

The event, called GirlsUp, is Maeve’s mother’s doing. Kelly Murray got a PhD in psychology, joined the Navy, became a professor and then had six daughters. Six. By the time the oldest was in junior high, Kelly had become very interested in the way society tells girls who they should be. How to look and act. And how these expectations sap their confidence just when they need it most.

Kelly wanted to get there first – to help girls figure out who they are before the world does it for them. So six summers ago, she set up camp, gathering her two oldest daughters and a half-dozen of their friends to talk about such things as self-image and self-reliance.

But Kelly didn’t know then what the program would mean to her daughters today, when it would carry a message that she could no long deliver herself.

Homework assignment: To whom do you compare yourself, and why?

“I compare myself to my dad,” Maeve says. “Because he works really hard at his job – and he takes care of all us girls alone.”

Sean Murray was at his law office downtown on the evening of June 26, 2009. He noticed the sky suddenly darken and unleash a furious storm, but he thought almost nothing of it.

Then his cellphone rang. “Get to Children’s National Medical Center,” a friend told him.

Kelly, 40, and the five youngest girls – Meghan, 11; Sloane, 7; Maeve, 6; Quinn, 2; and Kieran, 9 months – had been at the Chevy Chase Recreation Association for a swim team pot luck. When the rain started, the girls and two of Meghan’s friends piled into Kelly’s minivan. She was driving down Connecticut Avenue, less than a half-mile from their house, when a massive oak branch crashed down onto the van.

Sean arrived at the hospital just as his family emerged from a train of ambulances. He began counting heads.

“You’re just, ‘Whoa – what’s the deal? Where’s Sloane? Where’s Mom?’” he recalls. Then a social worker escorted him to a private room and told him that his wife of 13 years and their effervescent 7-year-old were dead.

In that moment one thought enveloped him – This existence is over – and was immediately swallowed by another – This existence is more precious than ever before. Because there were five other children out there, “and I’m now the be-all and end-all of their life.”

Meghan lay in the hospital with minor injuries and someone had put the babies to bed when Sean sat down with Jillian and Maeve. “It was just something that you never think or want to do in your life – to tell your kid that their mom passed away,” says Sean, now 45.

A friend who is a grief counselor gave him the words that he’d start to say on repeat. “I’m going to take care of you. I’m not going anywhere. I love you and your life is going to be good.” He would say that even when he wasn’t sure about the last part.

The night before the funeral, Sean kept vigil over the bodies of his wife and daughter at the Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament in Northwest Washington. “You could just say things and be with her,” he remembers of those hollow hours before dawn.

Sean met Kelly during Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport, R.I. He was the New Jersey-bred son of Irish immigrants. She’d grown up in Hawaii, Kenya and California. She was smart and beautiful, but Sean was more impressed by her vibrancy and sense of adventure. “She was always sort of excited about stuff,” he says.

Two years later they were married, and Jillian was born less than a year after that. Sean always thought that four kids seemed like a good number, but then they just kept going. “Once you have more than four, you almost don’t even notice the difference,” he says.

He and Kelly loved being parents. They threw themselves into the world of kids’ activities, coaching teams and volunteering at school. Kelly became a professor at Loyola University Maryland’s graduate center in Columbia and Sean went to law school at night.

Kelly was the kind of mom, Sean says, who “made everything fun.” Birthday parties had themes, such as “Fear Factor,” and she was a confidant not just to her own daughters, but also to her daughters’ friends.

“Kelly is one of these women who just embraced herself so fully, flaws and all, that she did the same for you,” remembers Debra Soltis, one of her best friends.

Sloane, outgoing like her mom, hated wearing shoes and made a new best friend everywhere she went. “She was kind of like the town mayor,” Sean remembers. “She was a very free-spirited, lively, just sort of happy kid.”

“I know you will keep Mommy company as you watch over us,” Sean said to her in his eulogy. “And that gives me more comfort than you will ever know.”

Kelly and Sloane were buried in the same coffin, the little girl’s head resting on her mother’s chest.

Outside the doorway of the Murrays’ brick colonial hangs a white flag painted with two rainbows. In their grief following the funeral, Kelly’s family went to the Eastern Shore. There, after another sudden summer storm, a breathtaking double rainbow appeared. They were sure it was Kelly and Sloane.

For a while, life was all questions and confusion. “How am I going to get through my teenage years?” Meghan remembers thinking. “How am I going to get through life without a mom?”

As a lawyer and a military man, Sean was used to going “to the book.” But there was no guide for this, for how a father should raise five daughters by himself. Yet there was a certain way in which he felt prepared. “Kelly was such a fantastic mom, and I literally felt like, ‘I’ve been trained for this,’ ” he says.

So he did what they’d always done. He kept the girls on their soccer teams. He insisted that they eat two vegetables every night at dinner. He cut their hair short in the summer and let it grow long in the winter. He expected them to pick up after themselves, to always try their best and to live up to their potential.

The first year was a fog, and the second was worse. After Kelly died, a former nanny agreed to stay with the family for a year. She was an anchor of familiarity and continuity. But she left. In the 12 months that followed, as shock wore off and sadness rushed in, six new nannies came and went before the Murrays found a fit.

Jillian was in middle school then. “Everything changed so fast that I really couldn’t keep up,” she says. “I was just kind of lost for the first couple of years.”

But every night, school uniforms were washed. Days were rehashed and arguments about who stole whose shirt were tamped down. Quinn and Kieran, who goes by Coco, became walking, talking human beings who joined the fray and added a new level of buoyancy. It makes Jillian and Meghan sad, but the truth is, the little girls don’t really know what they are missing. They were too young to remember.

“At least I got my mom,” says Meghan, now 16. “But they’re growing up completely without her.”

“Meg, what are you having for breakfast?” “Megs, what are you going to eat?” “Meghan. Breakfast?”

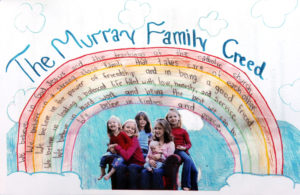

Sean will ask two more times before his sleepy-eyed teenager accepts a bowl of cereal. It’s just after 8 a.m. Quinn, now 7, is transfixed by the Disney Channel. Coco, 5, is playing the piano, on which sit framed photos of Kelly and Sloane. Middle child Maeve is at the kitchen table, beneath a “Family Creed” she made in the third grade. She wrote it on a rainbow.

“We believe in loving and serving others.”

“We believe in being responsible and honest to develop our talents.”

“We believe in the power of love and laughter.”

There is camp today, so soon it’s time to go. Quinn and Coco line up for a hug and a kiss from Sean. Maeve and Meghan already have piled into Sean’s Jeep. Jillian, on the verge of her senior year, is in Texas, competing at the Junior Olympics Track and Field Championship.

And at North Chevy Chase Elementary School, a couple of dozen girls are waiting to meet, and perhaps learn something about themselves.

The second session of GirlsUp was scheduled to take place two weeks after the accident. Debra Soltis had spent so many hours talking with Kelly about the program that she knew it had to continue.

She studied Kelly’s notes, developed a curriculum and taught the program to that year’s participants – including Jillian and Meghan. “Their presence in the room made the entire experience poignant and particularly inspiring,” she says.

The program now hosts 80 to 100 girls a year and holds three sessions each summer, including one at a youth center in Southeast Washington.

Jillian and Meghan are on a teen advisory board that helps run the camp. For them it’s about the mission, and also about their mom. “That’s when I feel closest to her,” Meghan says. “When I’m doing all the work.”

Today’s theme is self-expression, so the campers will talk about how to make their voices heard. They’ll meditate, improvise ways to navigate tough social situations, and take pictures of themselves.

And through it all, Soltis says, Kelly will be there. “It’s great that her own daughters get to continue to hear the wisdom and the guidance from her,” she says. “And it’s wonderful that many other girls get to hear it as well.”

At the end of each session, the campers decorate mirrors with words and expressions that describe their true essence. Maeve, who wears a rubber band bearing the names Kelly and Sloane around her ankle, spells out “happy,” “confident,” “friendly,” and “stronger.”

The Murray sisters were born almost in pairs. Today Maeve, who was just a year younger than Sloane, is the only one with a room of her own – the top bunk above her bed lies empty.

Each GirlsUp camper has chosen a personal mantra. Maeve paints hers in blue: “Just Keep Swimming.”

“It’s from Finding Nemo, ” she explains. “It means just keep going – even if, like, something bad happens.”

“I could say anything to her,” Jillian remembers of her mom. “That’s one of the hardest parts for me. If I have something going on at school or with friends, or if I’m just having a rough day, all I want to do is be able to talk to her.”

There’s a consensus among the girls that Sean is doing a good job. He’s naturally a hard-driving military man. “If I ask to do something and he says no, you don’t change his mind,” Meghan says. But, she adds, “he tries to be that soft side, too.”

Sean tries to talk about Kelly and Sloane – to mention their favorite movies or foods, to recall stories of things they said or did. But the girls, especially the older ones, find it more difficult.

“I can’t really do her justice,” Jillian says. She wants her sisters to know who their mother was, “but I feel like it’s hard for them to imagine her just through words.”

So she has found a different way: “I want to be there for them,” she says. “Like she was for me.”

And Jillian and Meghan still turn to their mom for support. They both silently talk to her at night before drifting off to sleep and – though they’d never mentioned it to each other – both have developed a habit of writing her notes.

Sean leaves discussion of matters such as bras and menstruation to aunts and grandmothers. As for boys, his philosophy is: “Idleness tempts the devil.” If the girls are occupied with other pursuits, he hopes, there won’t be time to get into trouble.

It has worked so far. The girls are on the honor roll and involved in almost every imaginable extracurricular activity. And they’re happy and chatty and outgoing, with magic tricks to demonstrate, bedrooms to show off and a pet turtle named Roxy who likes to make an occasional appearance in the kitchen.

“They haven’t just survived the tragedy,” Soltis says. “They’ve thrived.”

“Megs, what are you doing?” Sean yells, watching Meghan walk the last 50 yards of a warm-up lap at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. It’s the final night of a club track program that Sean started four years ago.

Meghan shrugs, smiles and jogs a few more paces to appease her dad.

Along with two dozen other athletes, the girls stretch, do jumping jacks and then take their places on the starting line for a mile-long run.

This is how Sean prefers things – busy and together. A year from now, Jillian will go off to college. During a 90-minute interview, it’s this thought, more than any other, that provokes an emotional silence. “It’s just going to be sort of an upsetting of the apple cart,” he says.

As the runners prepare for a relay, the western horizon grows dark. Soon there’s a slow rumble of thunder and a flash of lightning. The Murray sisters look at each other. Coco’s eyes well with tears and she points to the sky.

“I know, Coco,” Sean says. “It’s okay. We’re not going to put you in danger, okay, Coco?”

He will have to say it again and again as they pass out celebratory popsicles, clap for their coaches and hustle to the Jeep.

But the Murrays will make it back before the first drops of rain begin to fall. They’ll file into the brick house, where there will be dinner and showers and bedtime kisses. And where a flag with two rainbows always hangs, ready to welcome them home.

_______________

Editor’s Note: Some of the best journalists today are Irish American, including Ellen McCarthy, the author of this story on the Murrays, which ran in The Washington Post last August. In upcoming issues we plan to run such stories, by Irish Americans, of Irish Americans, as we find them.

Ellen McCarthy is a feature writer for the Style section of The Washington Post. Her first book, The Real Thing: Lessons on Love and Life from a Wedding Reporter’s Notebook, will be published by Ballantine Books in April.

Leave a Reply