A visit to the McCord Museum helps uncover the history of two of Montreal’s historic Irish neighborhoods.

In this tale of two Irish neighborhoods, leafy and modest Point St. Charles is in some ways unchanged from its heyday as a gritty Celtic enclave while just across the Lachine Canal, Griffintown bristles with cranes erecting a phalanx of condos from the ashes of factories and working-class residential blocks.

What ties them forever is the canal, almost whimsically named after a time when many of Canada’s inland waters were probed as potential avenues to the Far East, or La Chine, China.

It was the making of the Irish, and the death of some of them.

The McCord Museum on the bucolic McGill University campus has a display of two pages of a canal pay ledger of 1822. Of the almost 50 entries, only one is French. There are Rileys, Kellys, and Cahills working for an average pay of 15 shillings for six days of work, many of them 10-hour shifts.

The canal builders loved the Irish because they were strong and could work all day.

The Lachine Canal they dug fostered an industrial boom as it bypassed rapids on the St. Lawrence River and provided inexpensive transport for factory goods. In 1848 it was enlarged, providing more work.

According to the McCord Museum archives, Montreal grew by 54 per cent between 1852 and 1871 to 107,000 souls. Most of that growth was Irish immigration.

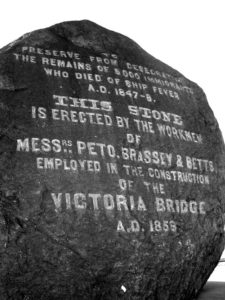

But it was the Irish migration in 1847 and 1848 that is recalled darkly with the Immigrants Stone in Pointe St. Charles. It is erected at the foot of Victoria Bridge to mark the burial spot of 6,000 Irish who died of typhus during the famine immigration.

Though many were passed as “seemingly well,” in official immigration parlance, at a quarantine station at Grosse Isle further north in the St. Lawrence, the stone’s inscription makes clear that the sickness ran wild on steamships bound for Montreal.

The sick and dying overwhelmed health authorities as 20 hospital tents were erected near docks. Nuns, priests, doctors and the sitting mayor of Montreal also died as they sacrificed personal safety to minister to the wretched passengers.

On the final Sunday each May, the modern Irish community gathers at St. Gabriel’s Catholic Church for the March to the Stone, a procession of a few miles that honors the dead at a grassy plot.

The Stone, also known as the Black Rock, is a prodigious piece of work. Thirty tons of black granite dedicated in 1860, it now sits in a desolate area, but a recently formed group, the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation, seeks support to create a new park at the Black Rock.

The Point and Griffintown were among Canada’s first bleak industrial areas with housing cheek-by-jowl with factories and rail yards.And that produced activists like Joe Beef, the publican who has a small park named after him in Point St. Charles. But Charles McKiernan, his square name, straddled both communities in Montreal’s Sud-Ouest borough.

Still remembered in Restaurant Joe Beef on Notre-Dame West in Griffintown, “a drunken crawl from the historic Atwater Market,” its website notes, McKiernan was a working-class hero whose pub was the cultural center for a rollicking

Irish community.

He printed this proclamation to the community, according to a McGill University publication:

“He cares not for Pope, Priest, Parson, or King William of the Boyne; all Joe wants is the Coin. He trusts in God in summer time to keep him from all harm; when he sees the first frost and snow poor old Joe trusts to the Almighty Dollar and good old maple wood to keep his belly warm, for Churches, Chapels, Ranters, Preachers, Beechers and such stuff Montreal has already got enough.”

The New York Times was not impressed, dismissing his tavern as a “den of filth.”

Maybe that was because he had a menagerie of animals in house that included up to four bears, several monkeys and an alligator, noted the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network. Its account added that one bear, Tom, was said to consume 20 pints of beer per day, seldom spilling a drop.

Joe Beef claimed to refuse no one food and was a central figure in a strike by Lachine Canal workers in 1877.

The times are tame now compared to then, and walks and bike rides around both communities show a much reduced Irish influence as the neighborhoods are gentrified.

In the case of Griffintown, the population fell to less than 1,000 in the 1960s, not enough to support St. Ann’s Church. It was razed and is now a park with benches arranged like a church setting.

The Lachine Canal, which fell into disuse midway through the last century and was a dump for excavation material when building Expo ’67 and the 1976 Summer Olympics, is now reborn as a recreational route.

Walkers and cyclists and kayakers enjoy the walkways and waters, many stopping at the aforementioned Atwater Market, which is hard by the canal and has an amazing array of food and produce from Quebec provisioners.

Several of the clothing factories which once employed the Irish along both sides of the canal have been converted to fashionable condos, and the smart Hotel Alt has risen in the midst of the condo boom in Griffintown.

Restaurants like Le Richmond on Rue Richmond now occupy former factory space offering starters like veal Carpaccio with a black pepper and fennel crust and mains like ballottine rabbit stuffed with black pudding. The elegant setting, northern Italian cuisine and professional service are a long haul from the mean meals immigrants once consumed here.

For startling contrast, the Maison Saint Gabriel Museum and Historic Site in The Point showcases 17th century life in New France before the English, Scots and Irish arrived. It illustrates the progression of the homes and lands from school to farm and finally museum.

But even it has an Irish touch – the magnificent grandmother clock crafted in 1763 in Quebec City by James Hanna. Time has changed much of this corner of Montreal, but the clock still ticks precisely.

That os a picture of Louis Cyr.. not Joe Beef!

You should re-check your picture of Joe Beef. It seems to be Louis Cyr, a strong man in the late 1800’s. It is Cyr’s picture in Wikipédia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Cyr

Thank You!

That’s Louis Cyr right there, it’s even written on the picture.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/91/CyrLouis.jpg

Thank you all for the correction. The image has been updated – that’s the real Joe Beef right there.

Is there a walking tour of Irish history in this area? Directions to the stone, and the location of the fever sheds would be helpful.