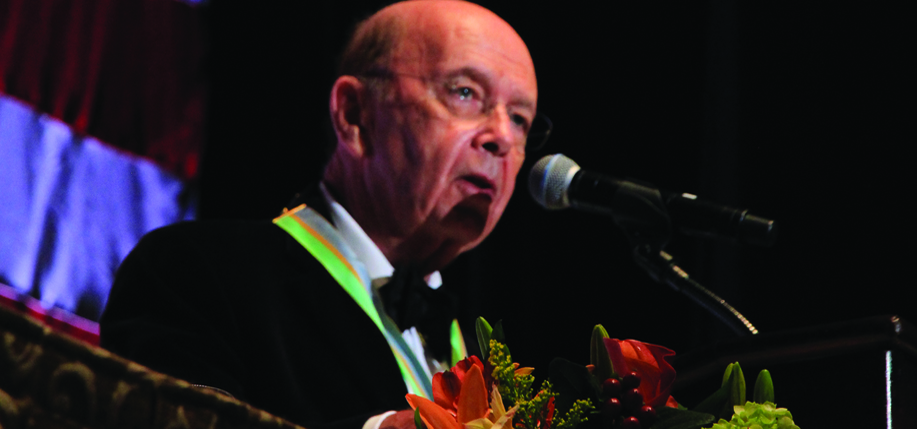

The American investor and businessman Wilbur Ross, Jr. led a consortium of investors who took a stake in Bank of Ireland in 2011 in order to reduce the risk the Irish state had to take. The investment also helped restore investor confidence in the ability of Ireland’s economy to recover. For his efforts, Ross was presented with the American Irish Historical Society’s Gold Medal on November 6, 2014, at the society’s annual dinner at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. In his acceptance speech, Ross, who Irish on his mother’s side, offered some insights into some of the lesser-known history of the Bank of Ireland.

From 1770 to 1782, all Irish government funds were held in the personal names of officials, but some of them kept the money, thereby creating government deficits. During the same period, many Irish private banks failed because of real estate speculation. (Does this sound

familiar?) So, in 1783, the newly independent Irish Parliament created Bank of Ireland as the sole depository for government cash. Private investors contributed £600,000 in Irish Government bonds that were trading at £80 but valued at £100, a nice mark-up. Once the bank had earned a real £600,000, the bonds were canceled, eliminating one-third of the government’s indebtedness. It was a combination Ponzi scheme and government bailout – the first of many in European history.

The bank was the first official issuer of currency and profited by printing paper money. Notes were engraved on the same paper and in the same dimensions and denominations as English Pounds Sterling, but also stated an official exchange rate of 13 Irish to 12 English. Ireland previously had no paper money, and its coinage had been limited to copper coins versus the gold and silver English coins that also changed hands there. Bad Irish coppers repeatedly drove the gold and silver coins out of circulation, causing periodic shortages, and creating recessions. Paper money solved the monetary supply problem, but led to forgery. Soon, Mr. Foliett Whiteway became the first convicted forger in Irish history, and forgery flourished despite increasingly harsh penalties. Finally, the Irish Parliament in 1797 decreed the death penalty for forgery, which did bring it under control somewhat.

Religion was another issue for Bank of Ireland. Catholics could buy shares only after swearing adherence to “An Act to Enable His Majesty’s Subjects of Whatever Persuasion to Testify their Allegiance to Him,” but the Board required prospective members to swear to Parliament’s “Act to Prevent the Further Growth of Popery.” The Board, therefore, included no Catholics, although it did include a former Catholic who recanted his faith in order to join the board. However, Irish Protestants were never on time so each newly-elected director deposited five guineas from which would be deducted a one shilling fine for fifteen minutes of tardiness and two shillings for an hour. Fines actually became a profit center for the bank.

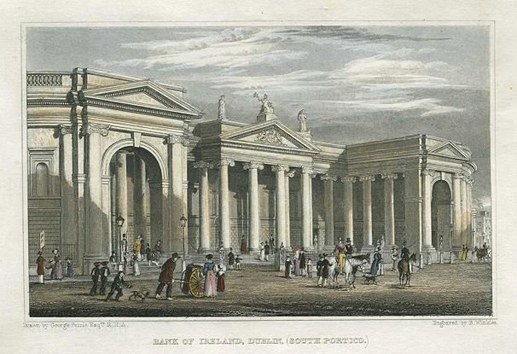

Another challenge was real estate. The bank’s original building abutted an open sewer into which a cashier’s carriage soon fell, costing the bank ten guineas in damages. So they purchased a new site from, of all organizations, the “Commissioners for Wide Streets,” and hired Sir John Soanes, Bank of England architect, to design a building. The bank wanted no windows, just like the Bank of England, but Soanes convinced them that their location was more secure than Threadneedle Street and that Iron bars on the windows would suffice. He cautioned though, to use non-combustible building materials and to store large quantities of water inside the bank, just in case. They wisely accepted his advice.

The bank’s original charter did not authorize branching but in 1801 the bank opened a branch anyway. In fact, it opened 94 branches and 48 sub-branches over 128 years before Parliament passed an act permitting branches. The bank similarly ignored the prohibition against incurring liabilities in excess of its capital. Until 1932 its charter had also provided that shareholders were liable for any debts the bank could not repay. Fortunately, this provision was never tested.

The first branch had its own saga. When the Act of Union subsumed Ireland’s Parliament into the English one, the House of Commons was torn down and to prevent it from ever rebuilding, the bank was ordered to erect a branch there. They did so and again debated windows, this time creating just one small window on one of the top floors. Strangely, the adjoining House of Lords was not torn down. Instead, the bank took it over and made it into the public museum which still operates today. It exhibits a huge silver gilt ceremonial mace, which the Lord Chancellor consigned to Christie’s in London for auction when the House was disbanded. The bank sent a staffer to buy it, and he did but at a surprising four times the high estimate after a bidding war with an anonymous antagonist.

On the steamboat returning to Dublin, the staffer met the mysterious rival bidder who said that the Government had commissioned him to buy it as a present for the Bank of Ireland, not knowing if the bank itself was bidding. The mace, recently valued at £50 million, turned out to be a good buy.

Tales from the Vault

Leave a Reply