For all of the bluster surrounding the John Ford and John Wayne relationship, and the sizzling chemistry of Maureen O’Hara and Wayne, Scott Eyman’s book, John Wayne: The Life and Legend, is particularly insightful about how this magical trio managed to make such enduring films. While there’s plenty of gossipy sections about Wayne’s marriages and Ford’s tantrums, its great strength is its exploration of Wayne’s rise and what made him – as well as Ford and O’Hara – such great movie stars.

The year was 1926, and young Duke Morrison had a job to do on the Hollywood set of an Irish immigrant picture called Mother Machree.

Not yet 20 years old, Morrison – who would become better known as John Wayne – was tasked with herding a gaggle of live geese, which the ornery director of Mother Machree was using to enhance the film’s rural atmosphere.

Suddenly, Wayne heard someone yell: “Hey, gooseherder!”

It was the director John Ford. He’d heard that Morrison earned a football scholarship to the University of Southern California.

The bombastic Ford challenged Morrison to strike a three-point stance, then declared: “I’ll bet you couldn’t even take me out!”

The next thing Morrison knew, the director was barreling towards him.

“Instead of trying to tackle him, Morrison stuck out a leg and hit the director in the chest, knocking him down,” Scott Eyman writes in his brand new biography John Wayne: The Life and Legend (Simon & Schuster).

“[Ford] sat there and for a minute, it was a case of whether or not I had a future in the motion pictures – I didn’t realize how important it was then,” Wayne later recalled. “But he took it humorously and laughed like hell – and the crew laughed. When he laughed, they laughed – they waited their turn.”

According to Eyman, this physical encounter on the set of an Irish movie captured Ford and Wayne’s “fifty-year friendship in microcosm – goading and torment, followed by release and friendship.”

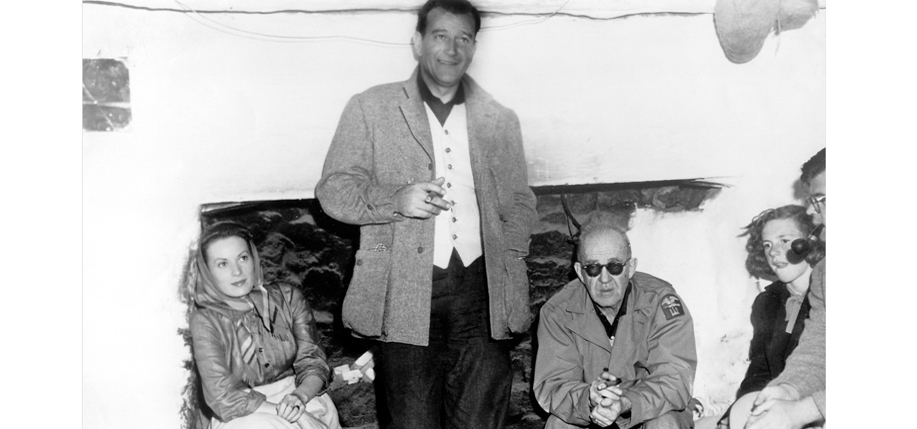

Ford and Wayne, of course, later teamed up with Irish actress Maureen O’Hara for the most beloved Irish film in Hollywood history, The Quiet Man. But the Irish trio had actually been making popular and critically acclaimed movies for over a decade. The new Wayne biography – as well as the 75th anniversary of the release of Stagecoach, the first Ford-Wayne blockbuster – offer a valuable opportunity to look back at the artistic collaboration, brilliant films and off-screen relationships of Hollywood’s Irish trinity: John Ford, Maureen O’Hara and John Wayne.

Ford and Wayne, of course, later teamed up with Irish actress Maureen O’Hara for the most beloved Irish film in Hollywood history, The Quiet Man. But the Irish trio had actually been making popular and critically acclaimed movies for over a decade. The new Wayne biography – as well as the 75th anniversary of the release of Stagecoach, the first Ford-Wayne blockbuster – offer a valuable opportunity to look back at the artistic collaboration, brilliant films and off-screen relationships of Hollywood’s Irish trinity: John Ford, Maureen O’Hara and John Wayne.

Irish Roots

John Ford (1894-1973) was easily the most prolific and arguably the most influential director of his generation. He was born in Maine to Irish immigrant parents and often said his birth name was actually Sean Aloysius O’Feeney. (For the record, Ford biographer Joseph McBride calls this “Fordian blarney.”)

None of which changes the fact that Ford had a passionate interest in Irish storytelling, evident in early directorial efforts such as Mother Machree as well as Hangman’s House, The Informer (based on Liam O’Flaherty’s novel) and The Plough and the Stars (based on Sean O’Casey’s play of the same name).

“John Ford was profoundly Irish in every way possible,” Eyman writes. “He was defensive, in total control of his art, if not his life, and he was some sort of genius.”

Maureen O’Hara, in the book, sums up Ford this way: “He was talented, and he was intolerable.”

Wayne, meanwhile, was different from Ford, who often acted as a (sometimes abusive) father figure to the rugged actor. Wayne, according to Eyman, “had grown up in a poverty further afflicted by [his mother] Mary Morrison’s shanty Irish pretensions.”

Ford spotted a quality in Wayne that few actors had.

“He was the only person I could think of at the time who could personify great strength and determination without talking much. That sounds easy, perhaps. But it’s not. Either you have it or you don’t.”

The Early Years

The first of many great Ford-Wayne movies was 1939’s Stagecoach, also starring Claire Trevor. Filmed in Ford’s iconic Monument Valley, Stagecoach remains one of the most influential films in Hollywood history. The John Ford Ireland Symposium in Dublin celebrated the film’s 75th anniversary this past summer, noting that Orson Welles called it a “perfect film” and watched it some 40 times while making his own masterpiece, Citizen Kane.

Stagecoach was nominated for numerous Academy Awards in a legendary cinematic year that also saw the release of The Wizard of Oz, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and another Irish-themed classic, Gone with the Wind.

Astonishingly, that same year, Ford also directed Drums Along the Mohawk and Young Mr. Lincoln, both with Henry Fonda.

The following year, Ford and Wayne collaborated again on a seafaring film based on the plays of Irish American Eugene O’Neill entitled The Long Voyage Home. Ford swiftly evolved into a “tough, demanding coach whose approval Wayne craved,” Eyman writes.

Meanwhile, in 1941, Ford worked for the first time with a stunning 21 year-old beauty from Dublin named Maureen O’Hara, on the smash hit How Green Was My Valley, about the struggles of a Welsh mining family.

The War Years

World War II (1941-1945) brought disruption to America, including its movie stars. Ford made films for the Navy, as chronicled in Mark Harris’ excellent recent book Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War.

Wayne’s war years are a little more complicated. Given that he’d cultivated such a macho image, it has long been a source of curiosity that Wayne didn’t see action during the war, as stars such as Henry Fonda and Tyrone Power did.

As Eyman writes: “Contrary to those who feel it convenient to regard Wayne as a classic case of war wimp, it is clear that he did make some effort to get into the service.” By this time, however, Wayne was a movie star with family, which would limited his chances for service. Wayne took part in USO tours and was eventually cited by Irish American William Donovan for “Honorably Serving the United States of America as a member of The Office of Strategic Services.”

Eyman believes “the most medically valid” reason for Wayne’s deferments was a “recurring ear infection.”

The Golden Era

Following World War II, Ford made My Darling Clementine with Henry Fonda as well as Fort Apache, 3 Godfathers and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, all with Wayne.

With his star on the rise, Wayne would take a break from his hectic Hollywood schedule by spending “weekends on Ford’s yacht Araner,” Eyman writes. (Ford’s mother hailed from the Aran Islands.)

Wayne never failed to show his appreciation for Ford.

“I’d like to get up on housetops and shout out what I owe to [John Ford]” Wayne told gossip columnist Louella Parson in 1946. “I simply owe him every mouthful I eat, every dollar I’ve got, and practically every bit of happiness I know, that’s all.”

Maureen O’Hara was also busy in the late 1940s, sometimes appearing in four pictures a year, most notably Sentimental Journey (1946) and Miracle on 34th Street (1947).

But as the 1950s dawned, Wayne, Ford and Maureen O’Hara would collaborate on a trio of memorable films, still notable for their mix of comedy, drama, sizzling on-screen chemistry and – in the case of The Quiet Man – the most memorable, even controversial, Irish film in history.

Rio Grande

First up was 1950’s Rio Grande, featuring Wayne as Lt. Col. Kirby Yorke, stationed on the Texas frontier to protect settlers from Native American attacks. (The screenplay was written by Irish-born James Kevin McGuiness.) Yorke has not seen his son in years – that is, until he is stationed under his own father’s command, prompting the arrival of Yorke’s wife (O’Hara) who does not want her son in harm’s way.

Though best known for action sequences, Ford gets less credit for the kind of powerful, conflicted emotions O’Hara and Wayne display in Rio Grande. Though a strict taskmaster, “Espirit de corps was not an option [on Ford’s set]; it was enforced,” Eyman writes. “The cast and crew stayed at the same hotel… and ate their meals together. At night, there were more theatricals – Maureen O’Hara sang Irish songs, Victor McLaglen did vaudeville sketches… and Wayne had to sing.”

Over the years, rumors have swirled that Ford could be abusive to his entire cast – including stars like O’Hara and Wayne. Rio Grande co-star Claude Jarman Jr. said Ford “adored” O’Hara, adding “He treated her like a queen.”

O’Hara, however, pulled no punches, recalling Ford’s “vicious… extremely severe” abuse aimed at Wayne, according to Eyman.

Harry Carey Jr. later added that Wayne “was always frightened of Ford. He was more scared of him than I ever was. I got to know the old man really well, and Duke didn’t have to be that scared of him, but he was.”

Wayne, however, remained appreciative towards Ford, always viewing his mean streak as a motivational tool employed to make an actor – and thus a film – better.

They would need that for their next project, which no one thought would ever get made.

The Quiet Man

Ford had been trying to make The Quiet Man since at least 1944, when he wanted “O’Hara, Wayne, Victor McLaglen, and Barry Fitzgerald to sign,” Eyman writes.

But (proving William Goldman’s old saying that “no one in Hollywood knows anything”) producer Herbert Yates dismissed a film based on Maurice Walsh’s short story as “a silly little Irish story that won’t make a dime.”

Eyman adds: “For the next six years, every major studio in Hollywood turned down The Quiet Man.”

Once financing was finally secured, Wayne agreed to star, but only after making a more bankable Western for Yates (Rio Grande), and giving up his “contractually guaranteed” cut of the film’s profits for a “flat fee of $100,000.”

Finally, Ford “would be able to make his film. In Ireland. In Technicolor,” Eyman writes.

In an interview with Eyman, Maureen O’Hara fondly recalled working with Wayne.

“He knew his lines. He worked like a dog. He tried to make each scene the best he possibly could. He wanted to satisfy the fans who were coming to see the film… He was kind, he supported people. A good man.”

She added, however, that Ford could be “a totally perverse human being,” aiming insults at a member of the cast “all day long… just awful. Your heart would turn over for them, and you wanted to poke [Ford] in the nose.”

But O’Hara believes this was a tactic to make other actors “unsteady, ready to do a certain kind of scene. And the other actors would be totally involved with you, mad for you, unhappy for you. And then he’d shoot the scene.”

Ford also had a tendency to exaggerate when it came to Ireland’s famously bad weather.

“It was one of the finest summers I ever saw in Ireland,” O’Hara recalled.

Ford and Wayne stayed “rigorously sober” on set, with the exception of one slow day when Wayne had an afternoon off from shooting and drank a bit too much with the locals. But “he was ready to go by seven the next morning,” Eyman writes.

The Quiet Man cemented O’Hara and Wayne as one of Hollywood’s most memorable screen couples and Ford as the maestro in charge of a supremely talented Irish cinematic orchestra.

But what about things off-screen? For decades, rumors swirled that O’Hara and Wayne (at the time married) had an affair. O’Hara has long denied this while director Andrew McLaglen (son of Victor) added: “There was nothing personal between them, but that’s the way it is sometimes – that makes the best screen relationships, people that don’t really know each other on a personal level, but they can sure act it.”

The Wings of Eagles

As the 1950s progressed, the trio continued working together. Ford and O’Hara worked on the criminally underrated The Long Gray Line, about Irish-born West Point lifer Marty Maher.

Ford and Wayne, meanwhile, made what may well be their most enduring masterpiece, The Searchers.

It was in 1957 that Ford, O’Hara and Wayne made their final film together, The Wings of Eagles, also starring Ward Bond and Dan Dailey. The film explores the history of the U.S. Navy through the colorful character of Frank “Spig” Wead, with Wayne playing the lead and O’Hara playing his long-suffering wife.

Subsequent years would see Wayne, Ford and O’Hara do some of their best work. Ford and Wayne worked together on The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Donovan’s Reef, while Wayne shot The Comancheros with Michel Curtiz and Rio Bravo with Howard Hawks. In 1960, Wayne himself directed The Alamo.

For O’Hara, there was Spencer’s Mountain, The Parent Trap and Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation.

McClintock!, in 1963, featured both O’Hara and Wayne, and though not directed by Ford, it was helmed by a familiar name – Andrew V. McLaglen, son of Ford regular Victor McLaglen. The film was also produced by John Wayne’s son, Michael.

John Ford died in 1973, and Wayne died six years later, after finally winning an Oscar for his turn in True Grit. Maureen O’Hara continued working regularly, even teaming up with John Wayne in 1971’s Big Jake, and offering up a particularly memorable turn alongside John Candy in Only the Lonely (1991).

Her 2004 memoir ’Tis Herself was a best-selling chronicle of an eight-decade career.

In the end, there’s simply never been an enduring Hollywood relationship – on screen and off – like the one forged by O’Hara, Wayne and Ford. What was the secret? Was it Wayne’s grit and generosity? O’Hara’s radiance and toughness? Ford’s intemperate vision? Perhaps the answer can be found in the famous final scene of The Quiet Man.

Ford has wrapped up his wonderful Irish American story, and Mary Kate (O’Hara) whispers a secret into the ear of Sean Thornton (Wayne) before they run off.

Was the secret comical or dramatic? Sexual or romantic? Philosophical or crude?

The answer, simply, is yes. Because it is all of these things that made the Ford/O’Hara/ Wayne collaborations so great.

_______________

John Wayne: The Life and Legend, by Scott Eyman, is out now.

(Simon & Schuster / 672 pages / $32.50)

Leave a Reply