How one of the most important post-Civil War sculptors died in obscurity and is buried in an unmarked grave.

Lancelot (Launt) Thompson was born in the town of Abbeyleix, in what was then Queens County and is now County Laois, on February 8, 1833. He came to the United States in 1847 with his recently widowed mother, who had no means of support in Ireland. They settled in the Albany, New York area. Soon the 14-year-old was working as an office boy for James H. Armsby, surgeon and professor at Albany Medical College, with the hope of eventually becoming a doctor himself.

Albany at that time was a center for visual arts. Several painters and sculptors in year-round residence and more swelling their ranks from New York City and Boston during the summer took advantage of the beautiful scenery of the Catskills, Adirondacks, and the Hudson River.

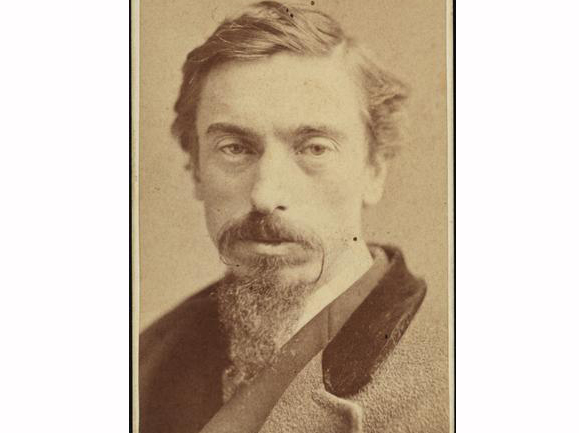

Having always possessed a talent for art, Launt, while in the early stages of studying anatomy, developed an interest in the human form and decided to specialize in anatomical drawing. A well-known sculptor living in Albany, Erastus Dow Palmer, saw potential in his work and hired him as a studio boy. He would spend the next nine years apprenticing with Palmer and developing his own unique style in sculpture.

Thompson and Palmer became friends, and the senior artist helped his protégé early in his career, getting his work exhibited and sold. The center of the art world in America at that time, as now, was New York City, upon which the young man set his sights. In 1858 he moved there, sharing an apartment with his friend, the young artist James Pinchot, who would later become very successful in the wallpaper business.

Thompson rented workspace in the Tenth Street Studio Building, an artistic and social center for the burgeoning New York art scene. He was soon working steadily, turning out cameos and marble relief portraits, some of which were entered into an exhibition at the National Academy of Design, and received favorable mention in the fledging art magazine Crayon.

Rose Madder, reviewing his cameos in 1859 for Irish America Weekly, wrote that they were “unrivalled in the delicacy of their execution.”

What first brought Thompson to the attention of the general public, however, was his marble portrait of James Capon Adams, known familiarly as “Grizzly Adams,” the legendary woodsman. Adams, who bonded with nature and refused to harm any animal, later became the subject of books, a movie, and a television series.

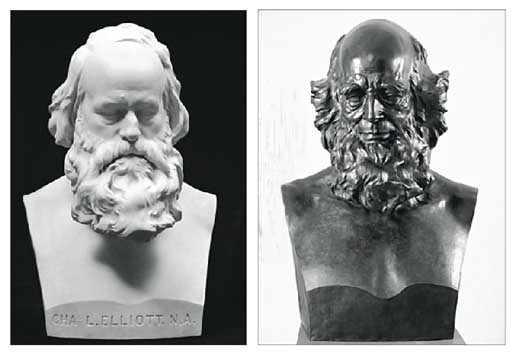

Thompson’s star was now rising, with more work and lucrative commissions coming his way. The Century Association, of which he was a member, commissioned him to do a portrait of another member, his close friend, the poet, journalist, and lawyer William Cullen Bryant, which is currently in the permanent collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Another commission came about in an unusual way – via his roommate’s family. Cyrille Pinchot, father of James, had served in Napoleon’s army before moving to the United States, where he took part in establishing the town of Milford, Pennsylvania. He wanted a bronze statue of his commanding officer placed in the town square.

Of course, by this time Napoleon was no longer an emperor, and Thompson’s sculpture, though considered by many to be an excellent work of art, for various reasons (mostly political) was never installed and remained at the Metropolitan Museum in New York for some time before finding a home at the Smithsonian.

The statue was unique in that it depicted the defeated Napoleon, with his head down. It was an unusual interpretation of an unusual commission, that of a defeated leader, especially one destined for a place of honor in a town square. However, this work led to other commissions, including an important one from the United States Military Academy at West Point, depicting Civil War Major General John Sedgwick, who was killed in the Battle of Spotsylvania in Virginia. In addition to the standing general, Thompson included a bas-relief on the base of the statue depicting Sedgwick’s death in the battle.

During his early years in New York City, Thompson cultivated an active social life. He frequented the famous Pfaff’s Cellar restaurant and bar and was considered one of the new avant-garde artists and writers referred to as “bohemians.” Among whom were the writers, Fitz-James O’Brien, William Winter, Thomas Bailey Aldrich and the artists Frank Bellew and Sol Etynge, Jr. who illustrated the work of Charles Dickens.

Two members of the assemblage who later rose to prominence were poet Walt Whitman and France’s Premier Georges Clemenceau. Lola Montez (see article in June/July issue on this Irish lady), sometimes dropped into Pfaff’s, as the guest of her friend Walt Whitman.

Thompson joined the Lotos Club and the Union League Club. He became a well-known host himself. A quote from the wife of his close friend, the poet and journalist Thomas Bailey Aldrich, may have hinted at problems to come: “Mr. Launt Thompson’s studio was one of the largest, and as he was always a great favorite, choice spirits were to be met there day and night.”

By “spirits” she was probably referring to interesting people but there may have been a pun intended with regard to the alcohol served. At any rate, it indicated Thompson’s outgoing personality – and perhaps his aversion to being alone.

Thompson was now doing so well financially that he could afford to take some time off to do a “Grand Tour” of Europe, so popular with well-to-do and up-and-coming young Americans of the time. His tour, however, was more than a vacation. He went to see first-hand, and study the great works of sculpture throughout Europe.

In 1868, he left for Paris with his friend and fellow artist, the landscape painter and student of Frederick Edwin Church, Jervis McEntee. After a brief stay in the city of lights, the pair traveled to Rome and joined up with Church and another member of the Hudson River School, John Ferguson Weir.

Thompson then went on to Venice, where he met up again with McEntee, who had preceded him and had rented an apartment with his wife. He stayed with them for a while, one floor above the poet Robert Browning, before venturing on to Florence, where he visited the famous Irish-American sculptor in residence there, Hiram Powers.

Thompson then returned to Paris where he was received by the American illustrator Gustave Dore. He finished the grand tour in London, spending time at the Royal Academy, the British Museum and Windsor Castle.

After what proved a valuable and highly educational tour, Thompson returned to New York City in 1869, and embarked upon what was to become the most productive phase of his career. After completing a bronze portrait bust of Sanford Robinson Gifford, leader of the Hudson River School, he was selected to create a statue for the town of Pittsfield, Massachusetts depicting a Union Army color-bearer. He then produced a life-size statue of Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, which was placed in front of the Old Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home in Washington, D.C., of which Scott was a co-founder. The statue faces the Capitol Building. For this work Thompson was paid the then formidable sum of $15,000. While he was completing this work he also executed a bronze statue of the Reverend Abraham Pierson, the first rector of Yale University, done posthumously.

It was during this time, flushed with success, that Thompson married Maria Louisa Potter. She was the daughter of Alonzo Potter, Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania, in St. George’s Church, a beautiful church in Troy, New York, which still has an active parish today.

Maria was the youngest of nine children of Alonzo Potter and Sarah Maria Nott. Her mother died giving birth to her and she was not raised with her father and siblings but with her strict, religious godmother, Mary Garretson. Her life improved when Eliphalet Nott, her maternal grandfather took over her care.

It is not clear how the couple met. Her grandfather lived in Schenectady, New York, not far from where Thompson lived in his youth, so they may have met as young adults, their difference in age being six years.

Thompson, while working on a commission of a portrait bust of Union College professor and Civil War officer Isaac W. Jackson in Schenectady, visited Maria as often as possible at her grandparents’ home, her grandfather was serving at the time as president of Union College.

The couple married, and in 1871, shortly after the birth of their first child, Lancelot Clarkson, they moved to Florence, Italy, where Thompson could find better access to stone and bronze and also a supply of inexpensive labor for his work. He flourished in Italy doing many commissioned portraits. But if Thompson did well, it was Maria who truly came into her own.

Italy became her adopted country where she would stay for the rest of her life. She became fluent in Italian. She became a gracious hostess to visiting family members, and Americans who passed through Florence. This period is described in a history of the Potter family written by her half-brother, Frank Hunter Potter in 1923:

“Her apartment in Florence [109 via de Serragli, next door to what was the studio of the by then belated Hiram Powers] was a Mecca for the whole Potter tribe. To say that we were welcome when we went to Florence is to understate it. I had the good fortune to spend many months practically in her household, and I never was happier.” He went on to say, “Her house became a resort of what was most distinguished and dignified in Florentine society. Her weekly receptions were delightful affairs.”

While in Florence, the Thompsons had two more children, both daughters, Marriette Benedict and Florence Howard. The sculptor kept busy with commissions from home and also turning out portraits of visiting Americans, such as Eliza Cross Pinchot, mother of his former roommate. He also kept up correspondence with his friends back home, especially the now very successful and famous actor Edwin Booth, who wrote regularly, keeping Thompson appraised of the cultural life in America.

It was during this time that Thompson finished his only nude sculpture, entitled “Unconsciousness” (1881) which he worked on for many years, and was one of his few works that was not commissioned, but done for his own satisfaction. It was based on a classic story of an American settler child kidnapped by Indians who was later found by her family but decided to stay with her adoptive tribe and marry its chief.

After six years in Florence, Thompson returned to New York City in 1881 by himself. There seems to be no record of why he left his family in Italy, but the demand for art and sculpture was skyrocketing among nouveau riche Americans and Thompson may have felt the need to be physically there to effectively compete. He probably planned to stay for a while, as long as necessary to re-establish himself and his reputation, and then return to his family in Florence. In addition, Maria loved her life in Florence and it was the only home their children had ever known.

Monuments dedicated to the memory of the Civil War were very popular in the 1880s, and Thompson was responsible for several: “The Eagle On The Globe” for the United States Regulars Monument in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and a statue of Admiral Samuel Francis Dupont, commissioned by Congress and first placed in Washington’s Dupont Circle but later moved to Rockford Park in Wilmington, Delaware. The most important one, however, was his only equestrian statue, that of General Ambrose Everett Burnside, ceremoniously unveiled in Kennedy Plaza, Providence, Rhode Island, on July 4, 1887.

After 1887 an inexplicable decline seems to have occurred in the life of Thompson. It could have been a combination of loneliness and overwork. From what little we know of Thompson’s personality, he seems to have thrived best while in the company of others, but the work of an artist is often a solitary affair. Without his wife and her active social circle, he retreated into himself. His commissions were not declining, which may have been a source of the problem: too much solitary work. At one point during this period he did a self-portrait, probably one of his only ones, in which he depicted himself as a kind of devil. This may have been an indication of his mental deterioration, if anyone was perceptive enough to spot it. Apparently no one was.

Things rapidly came to the surface, however, when he was arrested on December 2, 1890, at the behest of the artist John Snedecor, with whom he was sharing lodgings. Apparently, after a ten-day drinking binge, Thompson proceeded to wreck the premises, or as it would be termed today, “trash the place.” While being arrested, his behavior became even more erratic and there was an indication that he was suffering from delirium tremors. He was brought to the Jefferson Market Courthouse, accused of disturbing the peace.

Thompson’s arrest was covered by The New York Herald in an article entitled “Arrest of a Sculptor,” subtitled: “Liquor Drives Launt Thompson Crazy and a Policeman Has to Take Care of Him.” In fact, his arrest made just about every newspaper in the country, from big cities to small towns, as this piece from the December 11, 1890 edition of Michigan’s Bay City Times attests, “A few years ago Launt Thompson, the sculptor, was the lion of New York Society. He was the style, and while in the swim married a daughter of Bishop Potter. But social position, artistic ambition, success and a large income were thrown to the winds in the gratification of his appetite for strong drink, and a few days ago he was arrested for vagrancy and committed for a month to Blackwell’s Island, at the end of which time a commission will enquire concerning his sanity.”

While The Bay City Times article may have been rather unflattering, it indicates the fame that Thompson had throughout the country. While we don’t have the minutes of this commission’s meeting, we do know the results. Upon completion of his sentence he was transferred to Central Valley Hospital of Orange County, New York, a private sanatorium. It is unlikely that he could have continued to drink in jail, so his decline at this point may have been due to progressive mental illness. His excessive use of alcohol before his arrest may have, as is often the case, led to some sort of permanent, irreversible brain damage. For unexplained reasons he was then transferred to the State Homeopathic Asylum for the Insane in Middletown, New York.

Apparently, Thompson was still creating art while confined because a newspaper published by the asylum mentioned: “The well-known and distinguished sculptor Launt Thompson has been sojourning among us for several months. He has finished a bas-relief profile of Supervisor Cook’s son, little Talcott. This is an admirable piece of work, and shows for the artist, that his brain is still active in conception and that his right hand has not forgot its cunning.”

This amateur entry seems to be the last thing written about Thompson while he was alive. He had now fallen completely out of sight. The psychiatric records of his stay at the asylum are restricted due to privacy and confidentiality laws, so it may be impossible to find out what exactly what went on there.

The next news of Thompson was his obituary in The New York Times, September 27, 1894. The brief article covers only the highlights of his professional life: “In 1858 he went to New York, and having shown a remarkable talent for medallion portraits, he found ample employment. He became an associate of the Academy of Design in 1859, and three years later his bust of The Trapper secured his election as an academician. . . . Yale conferred upon him the honorary degree of M.A. in 1874.”

The Times discreetly makes no mention of the circumstances of Thompson’s death, which was attributed to throat cancer, heavy smoking being another one of his vices. His passing was also covered by practically every major newspaper in America.

Thompson’s decline leaves many questions unanswered. Was his wife kept informed of his condition? Did his family and friends try to help him? Had his antisocial and erratic behavior alienated them, or had he just become an embarrassment? Or was it simply that there was nothing which could be done. These and the other questions regarding his final days may remain a mystery forever.

Maria Louisa Thompson chose to spend the rest of her life in Italy. She became a writer of magazine articles with one book to her credit, The Legend of St. Gwendoline.

Maria Louisa may have become a bit eccentric. When she died on July 17, 1916, in Florence, her death was covered by The New York Times, which called attention to the strangeness of her will, executed in 1910. The article, entitled “Feared Burial Alive” bore the subtitle: “Mrs. Launt Thompson Asked for Cremation in Her Will.” The writer goes on to describe “an unusual will executed by Mrs. Launt Thompson, who died recently at Florence, Italy. One clause of the will says: ‘As I die a member of the Roman Catholic Church, if the permission of the church can by any possibility be obtained, I wish my body to be cremated as soon as possible after my death. If this cannot be done, I request that it be opened in such a way as to prevent my being buried alive, and that quick-lime be thrown upon it to consume it absolutely, and that my ashes be placed near the graves of my children.”

It is unclear when or why Maria Louisa, the daughter of an Episcopal bishop, converted to the Roman Catholic Church, and if Thompson, who never seemed to express any interest in any church, though most likely born into the Church of Ireland, had anything to do with it.

Launt and Maria’s only son, Lancelot, although born in America, considered himself a thorough Italian, and during World War I he volunteered to fight for the Italian Army. He worked as a bookkeeper and when he was rejected for health reasons offered his services as such to the local regiment. Every night after his day job he would work into the night doing their paperwork. This took a toll on his frail constitution and he soon died. His death was attributed to overwork for the cause of the war. He had written a book in Italian on the history of Florence, Il Trentino, la Venezia Giulia e la Dalmazia nel Risorgimento Italiano, which his mother translated into English after his death.

The oldest daughter Mariette Benedict worked as a nurse in France throughout the war. Surviving numerous attacks and bombardments. She received the Croix de Guerre in 1919 for her courageous work, and later became a successful sculptor in her own right, exhibiting in Paris and New York. She moved to the United States, married American businessman Lawrence Hayworth Mills, Jr., and settled in Morristown, New Jersey. They later moved to Paris, where they became friends with many writers and artists, especially Marcel Duchamp and Constantin Brancusi.

Younger daughter Florence Howard used her fluency in four languages to assist displaced soldiers and families during and after the war. She married an Italian count, Gian-Luigi Perticucci de Guidici and remained in Italy. Not much is known of her marriage except that it was not a financially successful one, as Maria wrote in her will: “I have left more to my dear daughter Florence than to my beloved Launt and Mariette because Flossie has married into wretched hopeless poverty, and I have wished to lessen so far as possible her hard privations.” It seems she was not a happy mother-in-law.

When he died on September 26, 1894 at the age of sixty-one, Launt Thompson was a resident of the New York State Homeopathic Asylum for the Insane in Middletown. His grave, in Middletown’s Hillside Cemetery, Section 13, lot 1610, Grave 1, remains to this day unmarked. It was purchased by a Maurice Thompson, who was probably his brother. No one attended his funeral. There may come a time when more light will be shed on his last, unhappy days, but his sad death in no way diminishes the triumphs of his life and the contributions he made to the development of nineteenth-century American sculpture. The works mentioned here are only a portion of his voluminous output. He joins the ranks of so many Irish-born artists and writers who grew, developed and prospered after arrival on our shores. Hopefully, his work will become more well-known and recognized by the contemporary American art public. ♦

Very interesting, but sad. Is any of his work to be seen in Ireland?

Also is information available on the involvement of the Irish in the arts or design in 19th and early 20th century US ?

An article in the New York Sun from October of 1894 has more on his life and last days:

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1894-10-07/ed-1/seq-24.pdf