Just around the corner from the Pantheon in Paris’s 5th Arrondissement is the former Collège des Irlandais, now the Irish Cultural Center (Le Centre Culturel Irlandais). Matthew Skwiat explores its storied past and current revival.

Henry Miller once said “to know Paris is to know a great deal.” His words seemed to take on a whole new meaning once one has traveled to France. One of the many things I learned while in Paris, besides a new appreciation for travel and the overwhelming wonder that Parisian food and art can inspire, was a great deal about the Irish in Paris.

It was, in fact, an Irishman who brought me to Paris. Oscar Wilde the subversive wit and playwright, like many Irish before him and since, fell in love with Paris. He was a fixture of the bohemian artistic circle, wrote his play Salome there, and after his fall from grace following his trial in 1895, he called Paris home. It was there where he died in 1900 (he’s buried in Père Lachaise), but not before quipping of his ill-furnished room, “this wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do.” Go indeed he did, but the hotel has survived him and is still standing, now as a five-star hotel. The conference I attended, “Wilde Days in Paris,” was due to take place at the Centre Cultural Irlandais in Paris to celebrate the 160th anniversary of Wilde’s birth.

It was here at the Irish Cultural Center where I stayed in Paris for just under a week, and while the conference was a success, I ended up learning more about the historic roots of the Irish college in Paris and the ties that continue to Ireland and France together.

The center itself is perfectly situated in the heart of Paris at 5 Rue des Irlandais, a few blocks away from the Pantheon and within walking distance to the Metro. Its presence is at once charming and bursting with history. The rooms are quaint, dormitory style, and reflect the former priestly roots of the past while offering lovely views of the center’s courtyard. It has just enough amenities, like free breakfast, to make it feel like you’re on vacation, but enough hospitality to make you feel at home. Besides the conference attendees, the center houses Irish students and scholars who want to study in Paris. The many rooms available for classes and the Old Library which was built in 1775 and houses over 8,000 volumes of manuscripts and printed books, intensify the intellectual foundations of the college and cultural center.

The history of the Irish cultural center and college is a unique story of knowledge, perseverance, war, and the centuries-old bonds between France and Ireland. The origins of a college in Paris originated in the 16th century during the turmoil of the Wars of Religion and the Reformation. While Henry VIII was converting England to Protestantism, Ireland along with France remained steadfastly committed to Catholicism. In 1578, an Irish priest, John Lee of Waterford, along with many other Irish Catholic priests, set up one of the first communities of Irish students and the beginnings of an Irish college in Paris at the Collège de Montaigu. Financial problems and inner struggles hampered the group initially, but recognition by Louis XIII in 1623 allowed Irish priests and scholars the right to receive and possess property. The University of Paris recognized the Irish college as a seminary in 1624, but the growing student body needed a larger and more permanent residence.

In 1672, Dr. John O’ Mollony, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Killaloe, along with other Irish bishops, set about establishing an Irish college. Louis XIV allowed them to obtain the College des Lombards, a derelict Italian college dating back to 1333. Once it was renovated and rebuilt, the Irish students finally had an official home in Paris.

As the 17th century passed into the 18th , the college continued to grow. By 1764, it had over 160 students, with Ireland sending many priests already ordained or those looking to take on holy orders. In 1769 a second college was built where the current Irish Cultural Center and College now sits. The two colleges became a beacon of Irish culture and knowledge that reflected the intellectual and cultural landscape of Paris. The colleges excelled in areas of theology and and the arts, but it was renowned as a center devoted to the Irish language with two Irish-English dictionaries published in 1732 and 1768 and an Irish language catechism in 1742.

This golden age of enlightenment did not last as war disrupted the stability of the two Irish colleges. The French Revolution fractured the connection between France and Ireland. Irish clergy members found it difficult to decide which side to support during the Revolution, either the state-sponsored government religion or the underground church which refused to accept the revolutionary changes. In 1792, both colleges were closed due to outbreak of the French Revolution and war with Britain. Many clergy who stayed behind were jailed in the Irish Cultural Center, but eventually set free. As the Napoleonic Wars continued, the clergy in Ireland refused to send any students to France, and in an effort to educate their clergy at home they petitioned the British government for the establishment of a college in Ireland. Maynooth College was born in 1795 following this petition.

A period of restoration followed in the 19th century, but the college was plagued by poor leadership, financial difficulties, and a dwindling student body. At this time the college was largely controlled by the French government, which displeased many of the Irish clergy. During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-1 the college was closed and turned into a field hospital. Once reopened it again became an important center of knowledge and was instrumental in providing priests to Ireland in the pre and post-Famine years.

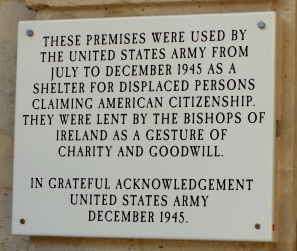

The 20th century brought with it new troubles to the Irish college as a law of the separation of church and state in 1905 in France all but closed the college. Two world wars saw the college close once again and the Irish clergy continue to dwindle. After 1945, the Irish clergy no longer showed interest in continuing an Irish seminary and granted permission to a group of Polish clerics to open a seminary. As a Polish seminary it had a number of impressive visitors, one of them being Karol Jósef Wojtyła, the future Pope John Paul II.

In 1997, the Polish community moved to new premises and the building was once again a cultural center for the Irish. A new restoration and renovation took place and it is now home to scholars and students alike looking for a quiet place to study or rest during their stay in Paris.

For me, the intersecting histories and voices of the college itself was something truly astonishing and memorable. While I would go on to visit the Eiffel Tower, Notre Dame Cathedral, Sacré Cœur, and Pére Lachaise, it was knowing I had a place just as historical to go back to that made it all the more magical. So not only did I get to know Paris, but I left knowing a great deal about the Irish as well.

I read that an ancestor of mine may be buried within the chapel. His name is Simon Luttrell of Luttrellstown, County Dublin. He was exiled from Ireland by the English after King James’ defeat at The Battle of the Boyne. I traced him to France as being a mercenary, training the French. I read (somewhere) that he was buried in the chapel of the then Irish University. Can you confirm if this is true, or not? I was in Paris this past June (for one night), but did not have the time to make it to the cultural center. Any help you may provide would be greatly appreciated.

Slante’ Ricardo

For the last six years I have arranged rooms for at least fifteen people to spend the month of July at the Centre Culturel Irlandais in the 5th Arrondissement. It is our little paradise in Paris, with easy access to the Métro in three directions, a 5-minute walk from the Rue Mouffetard, with its open-air markets and restaurants, along with the Roman Arena down the hill, for a huge dance on Bastille Day, and the Cimetière de Picpus, where we celebrate the Fourth of July at the grave of the Marquis de Lafayette, along with other Americans who find their way there to honor the great Frenchman who helped us gain our liberty. Vive la France!

Michael Heffernan

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Yes, in my last day in Paris I decided to go down the rue and check out that little cemetery. Delighted to discover the tombs of M. LaFayette and his faithful wife.

Nathalie

I’m organizing my group for July 2017!

Nathalie,

I am organizing my group for July 2017.

Michael Heffernan

heff1942@aol.com

Nathalie,

I am organizing my group for July 2017

I am the great grand niece of the Reverend Patrick Canon Glynn (1853-1921) from Kilmaley, Co. Clare. He was a close friend of my grandfather Thomas Fitzpatrick and I admire the Canon’s involvement with his parishioners. If I am lucky to get more information on him, I intend doing a little booklet for the family. I understand he was in the Irish College in Paris.

He was probably in Paris circa 1880 but not sure. Would there be a student who had a little time to research his time in Paris and why he was there? Thank you, Deirdre