The North’s Dark Star Became a Prince of Peace in a lifelong journey from firebrand to peacemaker.

I was at the Battle of the Boyne site in Oldbridge, County Meath, 30 miles from Dublin in May 2007 when Ian Paisley as the First Minister of Northern Ireland made a visit at the invitation of then Irish leader Bertie Ahern.

It was an extraordinary time when a power-sharing government had risen from the ashes of the old Stormont in Belfast and Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness shared power.

The Battle of the Boyne was the iconic Ulster Unionist battlefield as sacred as Gettysburg or Normandy beaches to Americans.

It was unthinkable that a Protestant leader of Northern Ireland would be officially invited to the battlefield where Catholic hopes of independence had died rather like the French inviting the British to Waterloo.

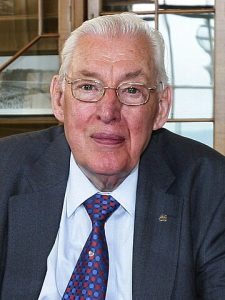

Yet here was Paisley, still with a booming voice, though he was 81 at the time, physically dwarfing everyone around him.

As he walked around the battlefield you had the deep sense of witnessing history that the 350-year-old battle was finally being reduced to a historical artifact, not a yearly rallying cry for more bigotry.

As Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Charlie Flanagan noted on Paisley’s passing, it was truly historic.

Flanagan said, “I recall especially that historic occasion when Dr. Paisley and his wife Eileen took part in the opening of the Battle of the Boyne heritage site. That day represented what many had worked so long to achieve, cooperation between North and South with recognition of our shared history and heritage. On that occasion, Dr. Paisley spoke of his love for ‘this island we jointly hold together.’ He spoke of how he wanted ‘the best for the people of every part of this island.’”

It was certainly a moment to recognize history in the making. Without Paisley, there would be no power-sharing government in Northern Ireland. No other political leader, like Nixon going to China, had built up the credibility with the hardliners that allowed him to do a deal with the hated Sinn Féin.

Once Paisley had been the dark star of Irish politics, bitterly opposed to any compromise on Northern Ireland being British. He was there from the very beginning of The Troubles. He was in the tradition of Hugh “Roaring” Hanna, a fundamentalist preacher of the late 19th century who opposed Home Rule and the pope in equal measure.

In 1963, he led a protest march at the lowering of the Union Jack to pay respects to deceased Pope John XXIII. A year later he caused a riot when demanding that an Irish tricolor be taken down in West Belfast. In 1966, he announced the creation of a loyalist group to protest the Irish Civil Rights movement.

He saw off successive Unionist leaders when they dared to reach out. Terence O’Neill, Brian Faulkner, James Chicester Clark were ejected from power once Paisley turned on them.

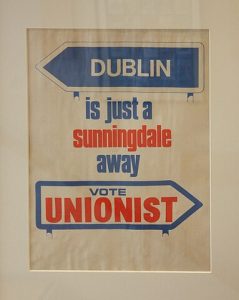

The man himself, it seemed, was never for turning. He brought down the 1974 Sunningdale Agreement and attacked the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 ferociously. His fiery oratory which stopped just short of advocating violence nonetheless led many to take up arms.

In the American context, he was pure Bible belt. He had interesting links to Bob Jones University in South Carolina where he got his doctorate. It was as fundamentalist a Bible belt college as could be imagined, often accused of outright racism. Paisley once saw it and the born-again Baptists in the South as a potentially lucrative source of funding for his political party, but it never worked out that way.

I once gatecrashed one of their events in Northern California and saw the preacher Paisley in full flow. It was quite a sight as the Book of Revelations got a work-out and the audience was worked into a frenzy.

Such a preacher’s gift caused many problems when The Troubles started. But in later years, driven I think (as many other leaders were), by the notion of not allowing The Troubles to feed into an endless loop for future generations, he saw making peace as his priority.

He came to America during the IRA ceasefire phase, and through a strange twist he and I arrived at a post-speech event as the first people there. For ten minutes we stood around awkwardly making very small talk. He seemed very ill at ease outside his normal environment and he bolted from the Irish-American dinner as soon as he could.

But when the opportunity to grasp peace came he took it, much to my surprise I have to say. I had pegged him as an irredentist Bible-belter whose prejudice against Catholics was too deep-seated to brook compromise.

Though he did not serve very long as First Minister, his impact was extraordinary. Privately Martin McGuinness extolled him as a man who above all kept his word — critical for the working of the government.

Now he is gone, a controversial figure who spanned the role of both troublemaker and peacemaker. He is proof that even the most irredentist can change – a hopeful thought as I look around Northern Ireland and other trouble spots and see irredentism everywhere. He shone a light that pierced an encircling gloom.

Leave a Reply