While health practitioners now praise the protein and amino acids provided by salmon, it has long had its place in Irish history simply because it is such good eating.

Every year more than 180,000 people visit Ireland expressly to engage in an activity that has been one of the island’s top drawing cards since the first intrepid hunter-gatherers arrived over 7,000 years ago: Fishing. And it’s one fish especially these avid anglers are after. Sporting hip-high waders, they claim stretches along one of Erin’s many crystal clear rivers to try their luck at reeling in the mighty salmon.

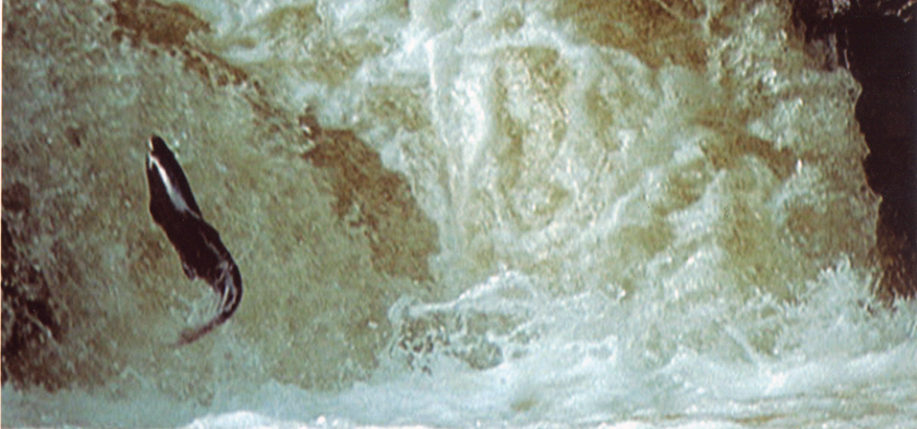

From February to mid-September salmon migrate from the open ocean into the coastal estuaries then up myriad waterways to inland lakes where they spawn. They are found in almost every stream, being most plentiful from May until late July, and fairly dance up the weirs where the rivers meet the sea. While visiting Ballyshannon, County Down in 1776, Arthur Young wrote in A Tour in Ireland, “I was delighted to see the salmon jump…the water was perfectly alive with them”

Young was far from the first to mention salmon in a literary work. The King of Fish appears over and over again in Irish mythology. Once upon a time, Lough Neagh overflowed its banks submerging the palace of King Eochaidh. All the royal family drowned but for one daughter, Muiraidhin (Born of the Sea). Trapped under the lake in her grianan (bower), the princess saw speckled salmon swimming all around her and prayed, “O Lord, make me a salmon that I may swim with the others.” Her plea was answered. Muiraidhin was changed into a salmon, her lapdog into an otter, and they lived happily together for three hundred years under the clear green waters.

One of the most ancient sagas tells how King Fintan escaped the Flood by leaping into Conla’s Well where he was changed into a salmon. Alongside the well stood a venerable hazel tree that was called The Tree of Knowledge because it produced both flowers and nuts simultaneously. Whenever a nut fell into the water, the hungry salmon gobbled it up. For each nut swallowed, he acquired a red spot on his back and absorbed another portion of the Tree’s wisdom. Ultimately, the fish became The Salmon of Knowledge.

The same salmon appears in the Fionn Tales. When Fionn MacCumaill was a lad, he studied with the most famous bard in Ireland, Finegas, who lived beside the River Boyne. One night, the poet came home carrying a reed basket in which lay a magnificent salmon. “I have patiently waited seven years to catch this fish,” Finegas told the boy. “Cook it for my supper, but on no account may you taste it because it has been foretold that a poet will eat this fish and gain all the wisdom of the ages.” Dutifully following his master’s bidding, Fionn broiled the salmon over a fire of sweet apple wood. He watched carefully as the fish cooked, lest it burn, but when a blister appeared on the skin he pressed it flat with his thumb and the hot fat burned his skin. Without thinking, Fionn put his finger in his mouth to relieve the pain and unwittingly had the first taste of the salmon. Instantly, he knew that something magical had happened and was afraid to tell his mentor what he had done. But Fionn was an honest man and Finegas was wise. The poet ungrudgingly forgave his pupil, knowing that Fate had bestowed the Gift of Knowledge on the proper man. From that day forward, whenever Fionn wanted to see the future or solve a problem, he only had to suck his thumb and all was revealed. He was the wisest of men, and for that reason the heroic Fianna chose him as their leader.

The salmon was believed to be such a magical fish that it peppers Gaelic phrases and proverbs. The old saying “Slainte an Bradain chugat” translates to “May you be healthy as a salmon” and conveys a wish for strength, agility and long life. The folk belief that some mystical connection exists between the salmon and the essential divine force is evidenced by the phrase “Bradan beatha” which means “life essence” or “soul.”

Aside from its legendary mythic and divine qualities, the salmon is prized for its superior taste. In fact, it is probable that salmon acquired its place in folk history simply because it is such good eating. In ancient times, salmon was always the central dish served at royal banquets where the method of cooking was identical to Fionn’s. A whole fish was rubbed with salt, impaled on a spit, basted with honey and butter, and roasted to a turn over an open fire. Accompanied by a salad of wild cresses, a loaf of crusty soda bread and cups of golden mead, it was a kingly repast indeed.

Salmon fishing is such an ubiquitous Irish sport that when a country person engages an angler in casual conversation and asks if he has caught a “fish,” the question usually means “Have you caught a salmon?” In Ballintrae, County Antrim, fishing boats and nets have traditionally been blessed on Saint John’s Day (June 21st) during the height of salmon season. After the ceremony, everyone sits down to a dinner where the menu features fish soup, fresh caught grilled salmon and the first harvest of new potatoes. Since Ballintrae stands on a bank of the River Bush, it’s not too surprising that the drink of choice is Bushmill’s Irish Whiskey.

At three years of age, a salmon weighs 8-12 pounds, and while it can be baked, broiled, or smoked, the most common cooking method is poaching. One 18th century recipe called for the whole cleaned fish to be seasoned, in and out, with a mixture of salt, pepper, dry breadcrumbs, finely grated horseradish, minced capers and a few chopped anchovies. It was then poached in a court bouillon made from equal parts of claret, white wine, apple cider and water.

In years past, when salmon runs were so abundant as to be considered “poor people’s food” vast numbers of the catch were filleted, poached briefly, then pickled for several days in a brine made from vinegar, onions, carrots and lemon juice. According to A Sportsman in Ireland (1897), a favorite breakfast consisted of “a bowl of fresh milk, a liberal allowance of cold salmon soaked in vinegar and a bottle of port wine.” When millions of Irish fled during the Great Hunger of the 19th century, tons of pickled salmon found a market in America where the immigrants hungered for a familiar taste.

While there is hardly a more delectable treat to bring home as a souvenir from a trip to Ireland than a side of oak smoked wild salmon, a fine Irish meal can be prepared by journeying no further than your favorite supermarket. The simplest way of preparing the King of Fishes is one of the best. Place salmon steaks on a foil-covered grill, season with salt and pepper, top with a pat of parsley-lemon butter, and broil until the flesh flakes easily (approximately 10 minutes). Add some finely ground hazelnuts to the butter, and perhaps you too will become as wise as Fionn MacCumail.

Sláinte!

People who say that eating fish is boring and they’d rather dine on meat have it backwards. The only thing that alters the taste of poultry and red meat is the way it’s prepared. Every fish has a unique flavor, and is a more easily digested, healthier source of protein. And the mighty salmon is the best of the best.

Not only is salmon a great source of lean protein and packed with nutrients like vitamin B12, vitamin D, selenium, calcium and iron, but it also has high amounts of Omega-3 fatty acids that are associated with many health benefits, from warding off depression and cognitive decline to reducing inflammation and the risk of heart disease.

Whole Poached Salmon (personal recipe)

1 cup water

1⁄2 cup white wine

1 carrot, peeled and sliced

1 onion, peeled and sliced

1 stalk of celery w/ leaves, cut in pieces

1 sprig of thyme

2 bay leaves

1 bunch of parsley

10 whole peppercorns

1 whole 8 pound salmon, scaled and gutted

Put the water, wine, vegetables, herbs and peppercorns in a saucepan. Bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer for 20 minutes. Line a baking pan with a large piece of heavy foil. Place the salmon in the center of the pan, and wrap it loosely with the foil. Pour the poaching liquid over the salmon inside the foil envelope, then crimp the edges closed. Bake in a preheated 300 F oven for approximately 1 hour. Let the salmon sit in the foil for 20 minutes, then lift it onto a large serving platter, and carefully remove the skin. Serve hot or chilled with boiled new potatoes and green mayonnaise. Serves 10.

Green Mayonnaise (Traditional Irish Cooking – Biddy White Lennon)

1 cup mayonnaise

1⁄3 cup packed fresh sorrel and watercress leaves,

stems removed

Blanch the leaves for 2 minutes in a pot of boiling water, then rinse under cold water and drain. Chop the leaves very finely and stir into the mayonnaise. Whirl the mixture in a blender to achieve a really smooth green sauce. Makes 1 cup.

Gravlax (Ancient Viking Salt-Cured Salmon Recipe)

1 side of wild Atlantic salmon (skin on), approx. 3 lbs.

2 large dill bunches, stems removed

1⁄2 cup kosher salt

1⁄2 cup sugar

1 heaping teaspoon white pepper

Mix salt with sugar and pepper, and set aside. Line a glass baking dish with plastic wrap. Cut salmon side in half. Place one piece, skin down, on the wrap. Cover with one-half of salt mixture. Place a thick layer of dill sprigs over the salt-sugar, reserving some for garnish. Spread remaining salt-sugar on the other piece of salmon. Place second piece on top of the first, this time with skin up. Completely wrap salmon with plastic wrap. Place another slightly smaller baking dish on top of salmon. Put two heavy weights in the uppermost baking dish. Refrigerate salmon for four days, turning salmon over twice each day. On the fifth day, brush dill and salt mixture off salmon, place salmon pieces end-to-end in a large platter and garnish with fresh dill sprigs. Slice thinly and accompany with slices of hearty bread. Serves 8 to 12 as an appetizer.

Leave a Reply