Fiction

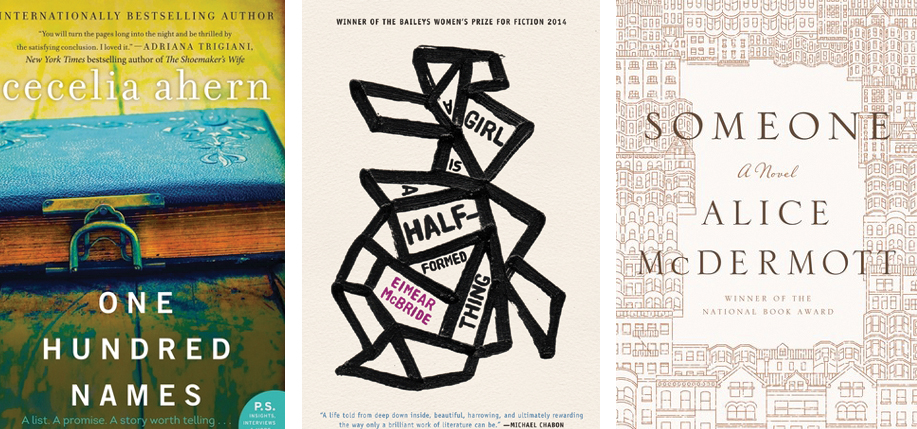

Someone

By Alice McDermott

Someone captures the universal experience of life’s joys and tragedies in the story of Marie Commeford, a most unremarkable woman. The novel begins in Depression-era Brooklyn as Marie, a myopic 7-year-old sitting on the stoop waiting for her father, chats with a teenage neighbor, Pegeen. Despite Marie’s bottle-bottom glasses, she still notes the young woman’s long instep and crowded teeth. And, as Pegeen opens the front door, Marie suddenly foresees her death, “her thin image in the glass shuddered like a flame.” That night Pegeen falls down a flight of stairs, dying instantly. It seems that the young girl with terrible eyesight sees everything.

At 17, Marie, believing she’s in love, finds herself engaged to a vile character named Walter Hartnett. When her fiancé invites her downtown to a swanky restaurant she dresses in her best Going-to- Mass clothes. It doesn’t take Walter long to announce that he’s marrying Judge Sweeney’s daughter Rita, explaining that it’s not because of her money but Rita is, well, better-looking and that makes for better-looking kids. Marie stumbles home to her brother Gabe, a still-devout ex-priest, who takes her on a long walk. When the heartbroken girl asks him if anyone will ever love her, he whispers, “Someone. Someone will.”

Someone does love her, the loving and loyal Tom; after her first child is born, Marie finally forges a bond with a life-long antagonist, her tough-minded mother. Both women embrace the secret code of Irish Motherhood: don’t brag about your children or exult in good fortune—that’s inviting bad luck. As her mother feeds her first grandchild, Marie’s infant son, she’s lost in a rapture she must conceal: “My mother glanced at me with sly eyes warning against the risk of drawing too much attention to the deepest joys.”

So much of Someone is not in what McDermott writes but what she doesn’t write, what lies in the spaces. She leaps back and forth through time and place, between the living and the dead, using scattered images, smells and sounds to spin her intergenerational narrative of Irish-Americans. Quick glimpses – a soldier’s uniform, a hospital waiting room, laundry on the clothesline and a half-cooked loaf of Irish soda bread – are subtle markers of where Marie is in the world of Someone.

The book ends where it starts as Marie’s mind goes back to that Brooklyn stoop with the doomed Pegeen and all the other ghosts that passed her way. Only a quiet genius like McDermott could manage to reveal the cycle of life in this small book with a big heart.

– Rosemary Rogers

(FSG / 232 pages / $25)

One Hundred Names

By Cecilia Ahern

Prolific Irish author Cecilia Ahern is known for her sparkling prose and plots that hook you and pull you in. One Hundred Names fits the bill. Part mystery and part coming-of-age story with a dash of romance, the novel follows Kitty Logan, a young and eager journalist whose commitment to getting the scoop has landed her in a heap of trouble.

Following a false accusation, Kitty be-comes a journalistic joke and a national pariah, and after the death of her beloved mentor and editor, Constance, it begins to seem like nobody is left in Kitty’s corner.

Grief-stricken and downtrodden, Kitty throws herself into her last shot at redemption: crafting the piece that Constance has left behind as the one story she always wanted to write. But there’s a catch: all Kitty has to go on is a list of seemingly random names she finds in Constance’s desk, and with a deadline looming, it’s up to her to piece together the story.

As she begins the daunting task of tracking down the owners of the names, she’s faced with the twin obstacles of a belittling new editor who’s skeptical of her talents and the disapproval of her oldest and dearest friend, Steve. Kitty will need her best reporting chops to pull it off, but she’ll also need to learn that there’s more than one way to get a story.

– Kara Rota

(William Morrow / 480 pages / $15.99)

A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing

By Eimear McBride

When Eimear McBride sent the manuscript of A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, her debut novel, to the editors at Galley Beggar Press in Norwich, the company hadn’t actually published anything yet. To say it was fledgling would be generous. But now McBride and the small U.K. press are close to ubiquitous names in the books sections of both U.K. and Irish periodicals.

Despite taking nine years to find a publisher and giving the editor who eventually did recognize its worth anxiety attacks over whether he should have listened to the big houses, A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing has been nothing short of a phenomenon. McBride won the Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year award, the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, the Goldsmiths Prize, and was shortlisted for the Folio Prize (she lost out to George Saunders). In July, she was announced the winner of the Desmond Elliot Prize, one of the most prestigious for first novels. The path McBride took to get to this place contributes in no small part to the novel’s appeal, which, one expects, will continue on this side of the Atlantic when Coffee House Press publishes it in the U.S. in September.

A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing is not an easy read, emotionally or technically. It challenges our ethics as much as our confidence in language to accurately express our fears, desires, drives, and histories. Narrated by an unnamed female protagonist literally from the womb to death in what McBride has termed “pre-consciousness” (as opposed to stream-of-consciousness), the book tackles head-on themes of sex, religion, child molestation, mental illness, family, and the divide between childhood and maturity. These may be familiar “Irish” themes embodied by traditional “Irish” characters – the molesting uncle, the religious mother, the culchie siblings – but McBride navigates the tension between cultural inheritance and contemporary reclamation deftly. In the end she produces a novel that is wholly unexpected, a novel that questions the very linguistic foundation of our identity. At the same time, McBride restores our faith in small presses and debuting authors to radically reinvent the genres we thought we knew.

– Adam Farley

(Coffee House Press / 227 pages / $24)

Poetry

The Holding Centre: Selected Poems, 1974 – 2004

By Harry Clifton

The author of seven previous collections of poetry with another forthcoming, Harry Clifton is experiencing a bit of a comeback, so the timing of this volume is no surprise. Nor is it surprising that the Blackrock-born poet’s first English-language selected poems in over two decades terminates at 2004, forgoes his most recent book (The Winter Sleep of Captain Lemass – Bloodaxe, 2012), revises old poems (including the title poem), and includes previously uncollected works, for the Clifton The Holding Centre offers is one caught in the perpetual throes of modern movement.

Taking for granted the facts of international travel and commitment, Clifton becomes a stand-in for the Irish diaspora, but also questions the formation of a global ethics and identity. He draws personas from an international coterie of poets and thinkers, from Kierkegaard to Euclid, Sandro Penna to Morton Feld-man, in an attempt to work through the problems inherent in being an Irishman, or any contemporary citizen for that matter, abroad. Ireland appears between the lines and in the background of Clifton’s work, rarely coming directly to the fore (“After Ireland,” a brilliant exception).

But despite the collection’s diagnosis of a deracinated modernity, early in the second of its six sections, Clifton acknowledges the terminality of disquietude in “Loneliness in the Tropics”: “Already this restlessness, / an hour old by the clock, // is wearing off….” Clifton here posits that sooner or later there will be equilibrium (though the ellipsis suggests an anxiety over just when that might materialize) and asks, resisting conclusion, of which two states will that equilibrium be born? He also asks whether equilibrium, as a form of stasis, is generative or destructive.

The title of the collection itself offers no such resolution. It performs double-duty work between its literal meaning as a detention center – a limbo between arrest and trial or escape and refuge, as is the case in the titular poem, set at the Mairut refugee camp between Thailand and Cambodia – and its figurative implications – a firm center in the middle of implied turmoil (Yeats’s gyres also alluded to). As a collection then, a minor critique may be that the poems are too regular, too similar, too settled in tone and diction while addressing the unsettled condition of a poet who has lived on at least four continents. But they also define a trajectory that is at once rooted in form and tradition that promises the potential for what some might call a late renaissance in his career. He has, after all, been living in Ireland now for the last decade.

– Adam Farley

(Wake Forrest UP / 156 pages / $16.95)

Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics

By Terry Golway

Tammany Hall has been synonymous with corrupt politicians ever since famed political cartoonist (and blatant anti-Irish, anti-Catholic bigot) Thomas Nast painted “Boss” William Tweed and his Irish American cronies as the “40 Thieves” of New York City. Irish American historian Terry Golway presents the Manhattan-based political machine in a much more complicated light in his new book Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics. Golway argues that the Irish Catholics who ruled Tammany actually influenced the progressive legislation more generally associated with the New Deal ideas adopted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This is a controversial, revisionist take, in part because the social legislation so beloved by liberal historians has not generally been associated with devout Catholic Irish Americans. Especially those whose record on race relations is not exactly pretty. Nevertheless, Golway makes a convincing case that less-prominent Tammany leaders – Richard Croker, “Silent” Charlie Murphy – made a great difference in the lives of the urban ethnic working- and lower-classes. Once Tammany graduate Al Smith became the first major Catholic political candidate to run for president in 1928, many of the legislative pieces of the New Deal puzzle were already in place. Perhaps the most interesting thing Golway does is make strong connections between the Irish struggle in the old world and the new. Too often, the Irish experience in America is depicted as a brand new beginning, wholly separate from what the Irish endured in Ireland. Aside from outlining Tammany’s role in social welfare legislation, Golway also convincingly argues that the trauma of the Irish Famine – exacerbated by Anglo-Protestant laissez faire attitudes in Britain and Ireland – fueled Tammany’s belief that government in the U.S. could be a solution to the problems facing many poor, urban ethnic groups. Golway, currently director of the Kean University Center for History, Politics and Policy, is not attempting to hide or cover up Tammany’s many sins. Still, Machine Made is a fresh, important look at a central subject in Irish and Irish American history.

– Tom Deignan

(Liveright / 400 pages / $27.95)

Leave a Reply