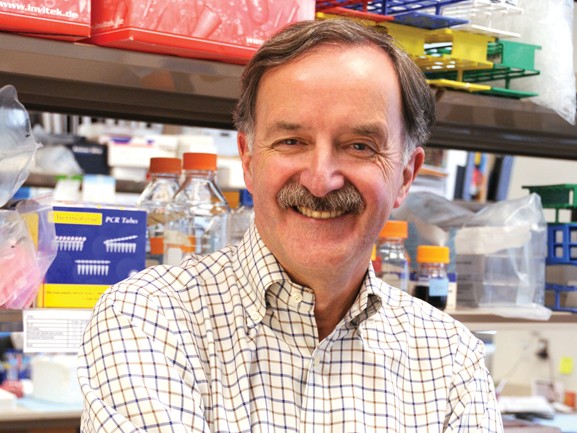

He works between the strands of basic discovery and clinical trial, national research and global connection, harnessing the power of diaspora. The inaugural Healthcare and Life Sciences 50 Keynote Speaker discusses the science of discovery.

Dr. Garret FitzGerald, a.k.a. “Big G” as faculty and students sometimes call him according to a 2001 Penn Medicine article, is a humble man with a proclivity for speaking about his research in equal medical and metaphoric terms. He fell into medicine through “a series of accidents” he thinks, though his earnest quest for knowledge is anything but.

Born and bred in Graystones, Co. Wicklow, he went to high school at a time when specialization in either the arts or the sciences wasn’t required as it is now. His grandfather had been a professor of Greek, he says, “So I did Greek and Latin and French and German and English and Irish,” but also rounded out his linguistics with math and physics. It’s clear his secondary school studies have stayed with him.

Now Dr. FitzGerald heads the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT) at the University of Pennsylvania. The institute, founded in 2004, is at the cutting edge of biomedical and public health research and aims to bridge the divide between basic science and what Dr. FitzGerald calls “the realization of clinical promise.”

Basic research is what is commonly called “blue skies” research, meaning “you study the sky because it’s there, not because you’re looking for a way to get to Mars,”

Taoiseach Enda Kenny presented FitzGerald with the Inaugural Science Foundation Ireland Award this past March. FitzGerald says. “And of course, most of our greatest discoveries that have affected human health or the way we live have come from that type of research. They haven’t come because somebody woke up in the night and said, ‘I’m going to develop a non-stick frying pan.’ They came because people went to the moon and a by-product was a non-stick frying pan.”

This, however, is highly problematic for Dr. FitzGerald and other researchers, because scientists can’t rely on serendipity alone to improve human life. What’s more, is that scientists sometimes have trouble relying on each other to efficiently make the transition from discovery to practice. “As you can imagine, people are educated and tend to be trained in either basic science or clinical research. Very few people have the training that actually straddles what we call the translational divide.

“Our area focuses right where basic science abuts the earliest stages of clinical investigation. And that’s actually the biggest hurdle in drug development… so our focus has been on really trying to increase the number of people who have the expertise that bridges the two very different disciplines,” he says. “Objective number two is to identify and reduce the barriers to their science in that space between basic research and early clinical development.”

In its decade of existence, the institute has enjoyed relative prominence. More than 100 people have graduated from the ITMAT with master’s degrees in translational medicine, and in addition to its core faculty of about 40, the institute also has what Dr. FitzGerald calls a “virtual faculty membership” of collaborators from across the Penn campus. Altogether, ITMAT has about 2,000 members, has been at the cusp of new research initiatives, and would appear to have made translational medicine into something of a zeitgeist. There are now centers for translational medicine across the world, including Singapore, Malaysia, Finland, Germany, and the U.K.

Despite these accomplishments, Dr. FitzGerald is hesitant to make any causal argument about the institute’s responsibility in the growth of translational medicine as a field. “It’s a cultural change,” he says. “Ours was the first institute of this sort in the world, and the institution undertook a commitment that this would take ten years or twenty years to change the culture.”

That cultural change has two parts, according to Dr. FitzGerald, one inside the academy, and one outside. In developing a drug, he says, “you need to harness the expertise of chemists, of pharmacologists, of informaticists, of experts in animal models, of clinicians, of trial design people, people of very different disciplines. Traditionally all those people act in distinct and often times competing departments within an academic medical center, and one of the things that we’ve really provoked is a much more interdisciplinary interaction between investigators within the institution.”

The second change he’d like to see, and is just starting to notice, comes from collaborations with outside private sector companies. “The traditional approach has been that large, vertically integrated companies like Pfizer or Merck would do everything from basic discovery all the way through to clinical trials and marketing for a new drug,” Dr. FitzGerald explains.

“Now that system is progressively breaking down so that the multiple modules along the way, the very different types of expertise that you need along the way, can be drawn not just from within a large, vertically integrated, company, but at various stages in the process from academic centers, from biotech companies, from other large, vertically integrated companies, from different geographies. We’re moving to a sort of modular approach to drug discovery and development. Our objective is to enhance the ability of our investigators to play in that space.”

In the years since the institute was founded, its members have become far more interconnected as researchers than those who did not elect to join and translational medicine has become one of the most bourgeoning fields in the medical industry. Ever humble, and thinking like a scientist, Dr. FitzGerald cautions that this correlation doesn’t mean causation.

“Now the problem always is whether this is just a coincidence over the time course of the existence of this institute, or if this is a result of the institute. And that’s a difficult one because we don’t have a control group.” But, he says, “I would say success has many fathers, and we can claim that we were one of them. We don’t aspire to be anything more than that.”

However success is defined for the ITMAT though, for Dr. FitzGerald himself, it is easily measured. Over the course of his 35-year career, he has published scores of research papers, worked in Ireland, England, and the U.S., and has received numerous awards, including most recently the inaugural Science Foundation Ireland Award this past March. In fact, he was instrumental in the process that gave birth to Science Foundation Ireland in the early 2000s. Moreover, in the previous 15-20 years, he has acted as an advisor to both Ireland and the U.K. and it is partly to his credit that Ireland now spends billions of government money on medical research. To put this in perspective, when Dr. FitzGerald returned to Ireland in 1991 for the first time in more than a decade, his lab’s research budget was roughly six million pounds he estimates, from a mix of private investors and external sources like the NIH and EU, while the entire national research budget for medical science for the whole country “was five-something,” he says.

Recognizing that Ireland could do more with public money, he attempted to replicate the system that had worked so well in the United States but was quickly met with resistance. He and colleague Desmond Fitzgerald (small “g,” no relation) managed to found the Centre for Cardiovascular Science at UCD and the Mater Misericordiae Hospital before it moved to the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. But trying to increase the amount of public funding in a way that mirrored the American system quickly entrenched the two of them in a political mire which Garret FitzGerald calls “a brief and bruising experience,” after which he left for Penn.

“But,” he concedes, “it turns out that one of the more constructive things I did for Irish science was leave, because shortly after that the government decided they might invest in science and I think the role that I could play was – I was very familiar with the realities and constraints of the system on the ground in Ireland and yet because I left I didn’t have a dog in the race.”

Now though, the science research budget is thriving and was largely maintained during the recession, signifying a public change in the perception of scientific research. That preservation, Dr. FitzGerald notes, “was almost counter-cultural” in a country where the popular icons were of literature, poets, and music, ignoring centuries of what he sees as a “grand tradition of science.”

Dr. FitzGerald hypothesizes that the Republican state, perhaps unintentionally, excluded that history of science “because it was mostly the Anglo-Irish Protestants who had the resources to indulge in science. So although we have many figures of considerable stature in our history of science, the Irish State, when it was founded, largely ignored them.”

Even Éamon De Valera, himself a mathematician, was contradictory, FitzGerald notes. “Despite the fact that he gave [Erwin] Schrödinger a home during the Second World War – Schrödinger stayed in his house – and he developed an institute for him, the Institute for Applied Physics, which still exists, the state he led never made an investment up until the early 1990s.”

And while this has certainly been a boon for the economy and for medical education in the years since, Dr. FitzGerald still, like any good researcher, sees room for improvement. Ireland, he thinks, is making a “classic mistake of government” by, perhaps counter-intuitively coming from FitzGerald, prioritizing translational research and shifting focus away from basic research.

“In other words, they wanted near-term gain and they wanted to introduce into their funding decisions the likelihood of commercial realization [as a form of] payback for the state investment,” he explains. While he admits this is a natural reflex of many investors, particularly national governments, he would like to see a readjustment of balance between funding for basic research and clinical research.

“A classical, small-village argument against investment in science in the past was, ‘Oh we’re a small country, we’re not going to make any big discoveries. We should let the Americans and the Germans make them themselves and then we’ll apply them.’ That’s nonsense. We’ve seen it in other domains of our activity. We can play on the international stage. And you don’t have to build MIT in Dublin to do it. You just need to enable people to realize their own potential.

“Will there be individuals who do amazing things? Yes, there will be, but increasingly science is a team sport and we want our guys to be able to play on Manchester United or Bayern Munich or whatever team you want to choose for science. If you take the players on those teams they’re drawn from everywhere. Barcelona has Messi and Neymar. So we want Irish players on those teams. That’s what’s realistic.

“What Ireland has absolutely got the capability to do is to invest and develop investigators who have the resource, the education, and the infrastructure to play in this global game. To be partners with people in Switzerland or the United States or New Zealand in pursuing big questions in science. We can and we should!”

The soccer analogy is an apt one. At the time we spoke, the World Cup quarterfinals were just beginning and national pride was in full swing. But, as Dr. FitzGerald observed, Messi, the star striker for Argentina, and Neymar, Brazil’s striking jewel, both play abroad between national tournaments.

“That’s where our traditions of people emigrating are actually our biggest strength,” the avid sports fan says, tying it together. “Because we emigrate, some of us go back, some of us don’t. It doesn’t matter. You’re creating a scientific diaspora that enhances the ability to develop the capital at home.”

“An ironic twist of fate is that that very paucity of resources propelled me out to train with world-leading figures. In a sense, the availability of resources to train within Ireland now reduces that creative insecurity that prompted people to go. And I think it’s very important in training to widen the perspectives and to go, particularly from a small country, to train at least part of the time, if not all of the time, abroad.”

In fact, he says, he thinks it’s a mistake to try to force people into the decision of whether to remain abroad or return. “What you do is you create the opportunity for them to return, and for those who don’t, you try to harness their goodwill to create the sorts of opportunities that I afford in my own lab.” Dr. FitzGerald is referring to his training program, in which he takes four high school students from Dublin and two students from UCD, his alma mater, to join twenty other students from around the globe to participate in a rotational research project for 6-7 weeks each summer.

It is interesting to think that one of the leading Irish figures in cardiovascular science and translational medicine almost wasn’t. When he’d told his grandmother he’d been accepted to medical school, she told him flatly, “Garret, any fool can be a doctor,” so he thought he would be a dentist, also in part because he was impressed with “a guy who had taken a tooth out.” That guy, however, told him not to pursue pre-dent and go into pre-med. FitzGerald says that advice made a huge impact, “so two weeks before I had to sign up for one or the other I signed up for pre-med. It wasn’t very strategic.” Then, he almost dropped out, but his future wife would persuade him to remain enrolled.

Finally, he had an instructor who made everything click. The teacher emphasized “that we didn’t know the answers and that medicine and science were a series of asking questions,” says Dr. FitzGerald, who has built his entire career around challenging common knowledge about existing drugs and systemic practices in the medical industry.

“You should be inquisitive and you shouldn’t accept dogma; you should question dogma. And that really stayed with me,” He pauses.

“I was always inquisitive, I guess.”

Well, at last I have found you again. I seem to have lost your email address when I changed to Gmail.

First of all, I woud like to offer you my deepest sympathies on your terrible loss.

And now of course -heartfelt Congats on all your tremendous achievements and awards. What tenacity!

love, and hope to be in touch soon.

Tara xxoo