Outside the city limits of ancient Rome at the top of the Janiculum hill is the 15th century church of San Pietro in Montorio. The church was supposedly built on the site where Saint Peter was crucified in 64 C.E. and its courtyard holds a small, circular, domed building meant to mark the exact spot of his crucifixion. The “Tempietto” (lit. “little temple”) was built by Italian architect Donato Bramante and is one of the best examples of High Renaissance architecture, prefiguring much that would come in the 16th and 17th centuries. A tourist site in its own right, Irish visitors to the Rome should have additional reason to visit San Pietro outside the city center – as many as 11 O’Donnell and O’Neill exiles are buried in the crypts below the church, including Hugh O’Neill and Rory O’Donnell, who led the Flight of the Earls in 1607.

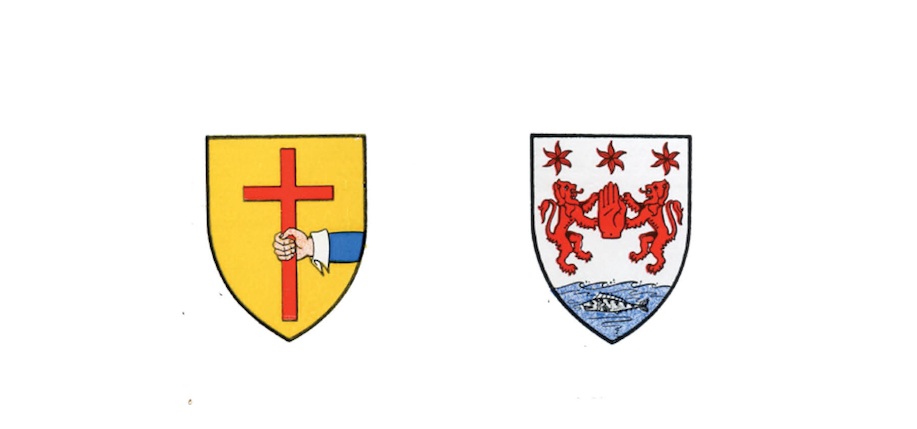

The history of these clans’ relationship is the history of Ulster in pre-Cromwellian Ireland. Though neither surname formally appeared until about the tenth century, both clans trace their lineages to Niall of the Nine Hostages, the famed fifth-century King of Tara.

The descendants of Niall, who had seven recorded heirs, were collectively called the Uí Néill and spread throughout Ireland, but the O’Neills that most are familiar with today actually take their name not from Niall himself, but from Niall Glúndub (d. 919), a descendant of Niall’s son Eóghan and a tenth-century king of the Cenél nEóghan, the kin of Eóghan, who occupied and lent their name to modern day Tyrone. Similarly, the O’Donnells trace the origin of their name to Domhnaill (d. 901), a descendant of another of Niall’s sons, Conall Gulban, and a ruler of the Cenél Conaill, Conall’s kin who occupied Tyrconnell, contemporary Donegal. It was thus that at about the same time both the modern O’Donnell and O’Neill clans arose in Ulster, in bordering territories.

The next six centuries saw the newly formed dynasties alternating between foe and ally, depending on the threat from English invasion of Ulster. When not banding together to prevent various invasions, the O’Neills and the O’Donnells warred with each other variously attempting to spread their own control over the North or assert their autonomy. Finally, the 1567 Battle of Farsetmore between the two clans led to a truce, in part because of the death of Shane O’Neill, head of the O’Neills at the time and a key belligerent. The heads of the clans rolled over and a new alliance was formed, just in time for the next English war.

The most famous instance of the clans’ friendship occurred in 1592, after the head of the O’Donnells had been imprisoned in Dublin Castle for almost five years. Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill (Red Hugh O’Donnell, 1572 – 1602) was seized by the English Lord Deputy of Ireland at the age of 15 in an attempt to prevent an O’Donnell/O’Neill alliance. Unfortunately for him, it only strengthened the clans’ relationship, and in 1592, Aodh Mór Ó Néill (Big Hugh O’Neill 1550 – 1616) orchestrated a jailbreak for Red Hugh. It would be the only successful escape from Dublin Castle.

Upon returning to Ulster, Red Hugh was named head of the name and clan when his father abdicated. Seeing an opportunity, Red Hugh compelled the father of Big Hugh to similarly abdicate, elevating Hugh O’Neill to the same position. Their alliance would prove crucial in the Nine Years War, with the O’Neills clandestinely garnering support from Philip II of Spain and gaining bargaining power over the English.

The war came to a head at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, the famed defeat for the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell, ultimately leading to the loss of the war, the death of Red Hugh, and the exile of the Earls of Ireland six years later. Red Hugh was succeeded by his brother Rudhraighe Ó Domhnail (Rory O’Donnell 1575 – 1608), who many blame, rightfully or not, for convincing Hugh O’Neill to flee, thus catalyzing the Flight of the Earls. Ultimately, both made it to Rome with the help of King Phillip III of Spain and were given sanctuary there. When they died, Philip allowed them to be buried in San Pietro in Montorio, which was financed by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain a century before and today is still the location of the Spanish Academy in Rome.

The legacy of the O’Donnells and O’Neills is effectively that of Ireland, plagued with what-ifs and could-have-beens. But it also illustrates a deeper connection to continental Europe and a kinship that extended into death and across national boundaries, much as the diaspora of the clans’ descendants does today. Excepting Antarctica, there are O’Neills from every continent, and, counting an Antarctic peak, the O’Donnells can claim a resident on all of them.

Of course, narrowing the focus a bit, this issue features two members of the clans back together again with our profiles of Ed O’Neill and Nora O’Donnell.

Leave a Reply