The Dream of the Celt

By Mario Vargas Llosa, translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman

Mario Vargas Llosa was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010 “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat.” Each of his books is a portrait of one or more individuals who set their course against the entrenched interests of the powerful. His first novel, The Time of the Hero, published in the mid-sixties and set among cadets at a Peruvian military school, very like the one Vargas Llosa had been sent to by his father, was derided by the ruling Peruvian generals as the product of “a degenerate mind.” In the ensuing years, Vargas Llosa has had reason to move from one country to another in order to continue to write and to stay free of such condemners. Each of his relocations has enabled him to absorb additional forms of language and literature, especially Portuguese, French, and English, even leading him to claim William Faulkner as his favorite writer.

What is especially remarkable about Vargas Llosa’s subjects is that he never seems to get anything wrong. Even the most consummate insiders hear no false note. His Dominican Republic in The Feast of the Goat is an utterly authentic recreation of that island nation in the time of the dictator Trujillo. His mid-nineteenth-century France – in The Perpetual Orgy, his non-fiction tribute to Gustave Flaubert – is faultlessly accurate. And now, in The Dream of the Celt, Vargas Llosa has written a lightly fictionalized, amazingly precise, and astonishingly perceptive life of the controversial Roger Casement, an early twentieth-century Irish figure whom most writers, whether of fiction or non-fiction, have failed to capture on the page.

Casement, who grew up in an Anglican family in Ulster, never attended university, and while still a teenager became a shipping clerk in Liverpool. Soon enough, he set off for adventures in Africa, long the destination of his dreams. There he came gradually to abhor the cruel treatment of the natives by Europeans, especially by the Belgians working for King Leopold II, one of the great villains of history. Casement’s report on the harrowing but quotidian atrocities perpetrated on the highly lucrative rubber plantations became a sensation, first in Britain, then throughout the Western world, leading to Casement’s knighthood and international fame.

The Dream is divided into three great sections, entitled “The Congo,” “Amazonia,” and “Ireland.” Vargas Llosa contrives to drop the reader, as if by parachute, into each locale. At first, one may lose one’s sense of direction, but gradually one becomes acclimated and, if not quite a native, certainly a seasoned resident. In the colonies of the Amazon, Casement encounters similar atrocities to the ones he reported in Africa, which triggers another sensational report. But as time goes on, Casement’s horror at the effects of colonialism turns him into an unyielding Irish patriot, one who sees vividly the parallels between the dispossessed natives of the Congo and Amazonia and the similarly dispossessed natives of his own ancestral island.

Casement’s involvement with the Irish revolutionaries and his subsequent capture, trial, and execution by the British are too well known to shock the reader. But Vargas Llosa sculpts such a rounded figure in his evolving portrait of Casement that we are left both sad and content at the end. Casement’s once-shocking “Black Diaries,” which narrate his homosexual encounters and were published by the British in order to discredit him, are put in their rightful – and subsidiary – place in the narrative. The author’s interpretation of their significance is so beautifully subtle that I would urge you to read about it in The Dream of the Celt without my further summary.

– Thomas Cahill

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux / 458 pages / $27)

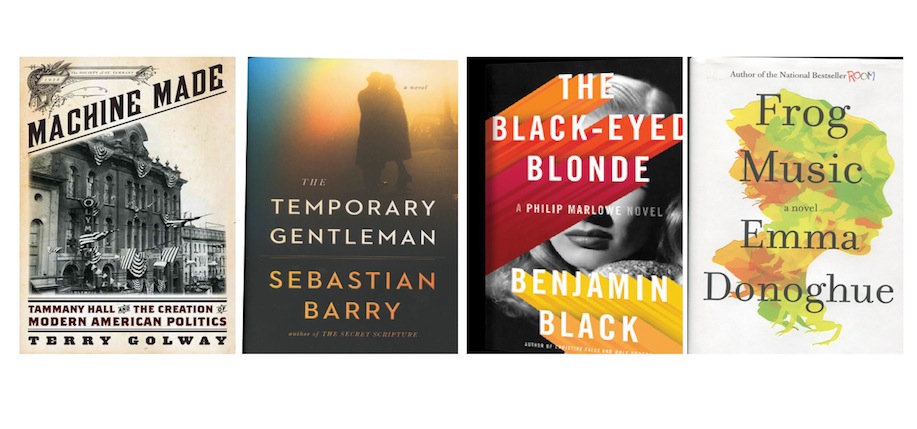

The Black-Eyed Blonde

By Benjamin Black (John Banville)

Booker Prize-winning Irish novelist John Banville has an alter ego known as Benjamin Black. As Black he has written eight best-selling crime novels. In his latest, The Black-Eyed Blonde, he revisits Raymond Chandler’s legacy of American noir, reviving Chandler’s brutally compelling and witty P.I., Philip Marlowe.

The novel is an entertaining read – a noir thriller reminiscent of the best of the genre. Certainly, Black’s mimicry of Chandler comes close to masterful in most of the novel. The women are beautiful, dangerous, and duplicitous – just as noir “dames” should be. Black does his utmost to present us with authentic Marlowe – a jaded first-person narrator whose world-view is rife with bitter witticism and often bizarre metaphor (“around here there are days in high summer when the sun works on you like a gorilla peeling a banana”).

The plot is pure Chandler, with more twists and turns than a drive through the Hollywood Hills. There are country clubs, gun molls, shady Mexican gangsters, playboys, rich kid drug addicts, and of course, the black-eyed blonde – a poor little rich girl who just happens to have been born in Ireland. Aside from a few minor linguistic stumbles (no 1950s P.I. would have a clue what a “cottage loaf” looks like or call his cigarettes “cancer sticks”), Black captures Chandler’s prose style. It is only in the Irish references that the novel feels off-key – the black-eyed blonde’s father was a compatriot of Michael Collins and was brutally murdered. When Marlowe hears the story, he is already familiar with the importance of the Irish Civil War and Michael Collins – an importance that Collins and Irish Nationalism just wouldn’t have had in the vernacular of 1950s L.A.

What Black attempts here is admirable, and aside from a few minor missteps, he accomplishes his goal of writing Chandler’s best-known anti-hero true to character while giving us a romp of a noir thrill ride.

– Yvonne C. Garrett

(Henry Holt & Co. / 304 pages / $27.00)

Frog Music

By Emma Donoghue

San Francisco in the 1870s – a parched and burgeoning city of debauched entertainment, lyrical music, salubrious pubs, and as it turns out in Dublin native Emma Donoghue’s new novel Frog Music, murder. Her new mystery centers on the real-life unsolved murder of Jenny Bonnet, a frog-catching crossdresser whom Donoghue weaves with vibrant delight throughout her story. Just as she had done in her previous novel Room (shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and Hughes Irish Novel of the Year), which was inspired by the abduction of Elizabeth Fritzl, Donoghue takes inspiration from the real-life complexities of the world and turns them into emotionally riveting fictions.

Frog Music is not Donoghue’s first foray into the realm of historical fiction, having captivated audiences with her moving and lusty portrayal of an 18th century working-class London prostitute in Slammerkin or with her book of short stories The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits. Donoghue is at her best when she inhabits the world she is writing about, bringing to life the crowded and stifling streets of San Francisco with “a stinking miasma of all the streams and soots San Franciscans can produce” while also conveying the fear surrounding the outbreak of smallpox that ravaged the city in 1876. Added to these fears is the pent up racism that colors San Franciscan society. Donoghue puts us right in the middle of Chinatown, where no doctors would venture over fears of contracting smallpox from the exotic “coolies.” Racist and stereotypical fears of newly arrived Irish immigrants like the McNamaras, who owned the saloon where Bonnet was murdered, are bitingly described as unintelligent and “potato-faced” from the novel’s heroine Blanche Beunon, herself a French immigrant. These descriptions contextualize the gilded 19th-century American West, allowing Donoghue throughout Frog Music to present the time period in a highly visual way, focusing on the less appealing aspects of society, warts and all.

As in all of Donoghue’s novels, the characters she creates center on the solidarity of relationships – in this instance that of Blanche and Bonnet and, more heartrending Blanche and her baby P’tit. Blanche herself is an immigrant from France having settled as a dancer and call girl in California with her ami Arthur and his friend Ernest.

What the novel needed was more aspects of Jenny Bonnet. Donoghue tells her narrative through the eyes of Blanche in a fractured and fragmented way, relying on flashbacks and fastforwards. The image we have of Jenny is incomplete and the reader waits anxiously for the scenes she tends to steal so effortlessly.

The relationship that solidifies the novel is Blanche’s journey with her son P’tit. We watch as Blanche goes from self-involved sex object to nurturing mother. Blanche rescues P’tit from an appalling shelter where he is nursed for over a year, and even though he is described in no flattering terms, the love Blanche feels for him comes across as sincere and palpable. The novel’s journey is just as much about who killed Jenny Bonnet as it is about the relationship between a mother and her son, a theme it shares with Room.

In the end, Donoghue pieces together a murder mystery and family drama of a very high caliber that uncovers the life of the rambunctious and ahead-of-her-time Jenny Bonnet, while infusing her novel with love, music, and frogs.

– Matthew Skwiat

(Little Brown / 405 pages / $27.00)

The Temporary Gentleman

By Sebastian Barry

Sebastian Barry’s The Temporary Gentleman is his eighth novel, and his third to deal with the history of the McNulty family. This time the narrator is Jack, brother to Eneas from The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty and brother-in-law to Rosanne from The Secret Scripture, the woman who was committed to a mental institution by her husband, Jack’s brother, and the local priest, for supposed sins of the flesh. (The book is now being made into a movie starring Vanessa Redgrave, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Jessica Chastain and Jeremy Irons.)

As in his other books, Barry writes about a country suffering from both the aftershock of British colonization, and the almighty control of the Catholic Church.

Jack, an engineer who lived through the Great War, is the “temporary gentleman” of the book’s title in that his commission in the British Army was never permanent. (The moniker was used, as a pejorative term to describe an Irish officer in the British Army who, for the course of the war, would be designated a “temporary gentleman.”)

As with many Irish who served in the British Army, Jack finds himself unable to settle in Ireland’s post-revolution atmosphere. Meanwhile, his wife, the beautiful Mae Kirwan, whom he met in college, is frustrated in that she has no role to play in the “new” Ireland other than that of wife and mother.

In 1957 Jack finds himself in Accra, along the Ghanaian coast, where he had been posted during the war. To better understand his predicament he decides to write down his recollections.

This story within a story technique worked well for Barry in Secret Scripture and it succeeds here too. We come to an understanding of Jack’s nature through his reflections, and that’s the beauty of Barry’s writing. He lays the evidence out without judgment, and though Jack is culpable of wrongdoing, in the end we see him as all too human.

– Patricia Harty

(Viking Adult / 320 pages / $26.95)

Leave a Reply