Scientists from Trinity College Dublin have shown for the first time that two genes involved in many neurological diseases act together to regulate specific aspects of protein production in nerve cells and allow the development of a simple form of memory called habituation. These findings have implications for our understanding of memory formation in general, and will also aid ongoing research in related diseases.

Habituation occurs when we are repeatedly exposed to a stimulus and our response is lessened over time as a result. Two everyday examples include our ability to stop hearing ambient noise when concentrating on a particular task, and the fact that we stop feeling the clothes we are wearing once we are dressed.

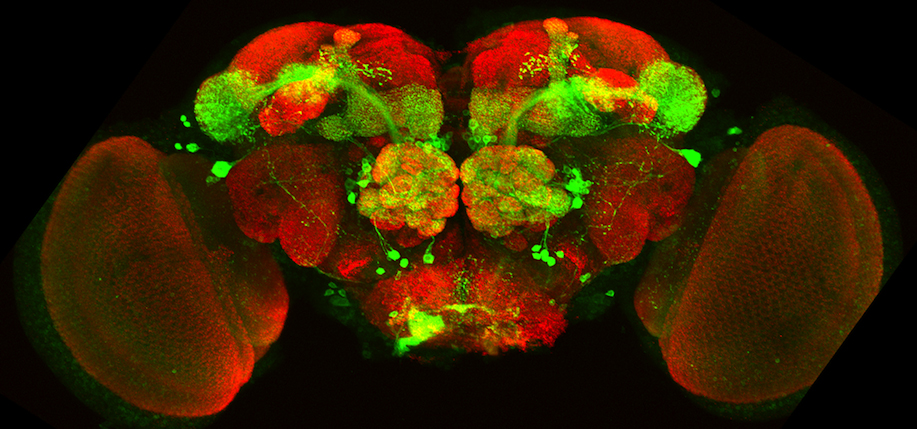

The scientists behind the discovery worked with fruit flies to explore the fundamentals of memory and learning and to investigate the molecular function of the two genes, called ‘Atx2’ and ‘FMRP’. Atx2 is associated with Motor Neurone Disease and Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 2, while FMRP is known to impact mental retardation and Autism Spectrum Disorder.

The Trinity scientists, led by Professor of Neurogenetics Mani Ramaswami, showed that flies that normally learned to ignore a familiar, unpleasant smell, failed to do so if they had defects in either gene. They proposed two potential explanations for defective protein regulation based on their results. Mutations that cause a loss of function in both genes lead to a failure to reduce protein production when associated proteins are not required, while an increased or altered function of the genes leads to a ‘hyper-repressed’ state in which the stimulation of specific protein production is prevented when these proteins are required.

Dr. Jens Hillebrand, Research Fellow in Genetics at Trinity and co-lead author on the paper, added: “It is nice to be able to potentially explain why FMRP and Atx2 diseases in humans are symptomatically different, even though the two proteins have rather similar normal functions.”

Irish Scientists Discover Genetic Basis for Memory Formation

Leave a Reply