On January 24, 1848 a handful of shiny metal found in the water channel below John Sutter’s lumber mill in Northern California launched the first world-class Gold Rush. Within seven years, the population of San Francisco swelled from 200 to more than 50,000.

More secure work than prospecting could be found on the vast cattle ranches of the original Spanish land grants, and many would-be prospectors from Central and South America ventured no further north than the Pueblo of Los Angeles.

It is estimated that more than 300,000 prospectors, merchants, and immigrants from around the world sought quick wealth on America’s West Coast during the California Gold Rush years. In 1876, the completion of a transcontinental railroad to Los Angeles changed Southern California forever.

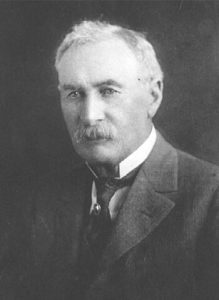

Between 1876 and 1900, the population of Los Angeles mushroomed from 7,500 to 102,500. Real estate developers and city fathers (often one and the same) were determined to build Los Angeles into the West’s most important metropolis. However, the upsurge in residents and industry created a massive problem. The regional water supply could not support further municipal growth. The engineer who provided the solution was William Mulholland.

Born on September 11, 1855, in Belfast, County Antrim, Mulholland ran away from home at age 15 and joined the British Merchant Navy. After several years at sea and inspired by tales of the California Gold Rush, he boarded a ship bound for San Francisco. Shortly after arriving, he set out on horseback to explore California, reaching Los Angeles in 1877. Years later, he wrote about his first sight of the city: “Los Angeles was a place after my own heart. The people were hospitable. . . . The Los Angeles River was a beautiful, limpid little stream with willows on its banks. . . . It was so attractive to me that it at once became something about which my whole scheme of life was woven.”

At the time, water flowed from the river to a large holding pool in the city via open ditches called zanjas, and men who tended them were called zanjeros. Mulholland’s first job in Los Angeles was as a well digger. After completing his day’s work from books borrowed or purchased with part of his meager income, he studied mathematics, hydraulics, engineering, and geology, and for recreation, he read classic literature, always seeking to further his knowledge of science and the arts.

One year later, impressed by Mulholland’s performance, Fred Eaton, superintendent of the newly formed Los Angeles City Water Company, hired him as a zanjero on the Zanja Madre (the main water conduit) and in 1880, he was assigned the task of overseeing the installation of Los Angeles’s first iron water pipeline. When Eaton rose to the post of City Engineer, Mulholland became superintendent of the LACWC. The working relationship that had developed between the two men would leave its mark on Los Angeles’s history and the history of engineering itself.

In 1898, Fred Eaton ran for mayor on a platform of establishing a new municipal water system and was elected to a two-year term. He created the Los Angeles Water Department during his administration and appointed Mulholland as superintendent and Chief Engineer. While in that post, he became the first American engineer to construct a dam utilizing hydraulic sliding gates to control water flow. Built at Los Angeles’s Silver Lake Reservoir in 1906, it served for almost 70 years. Government engineers adopted the method of building a Gatun Dam in the Panama Canal Zone.

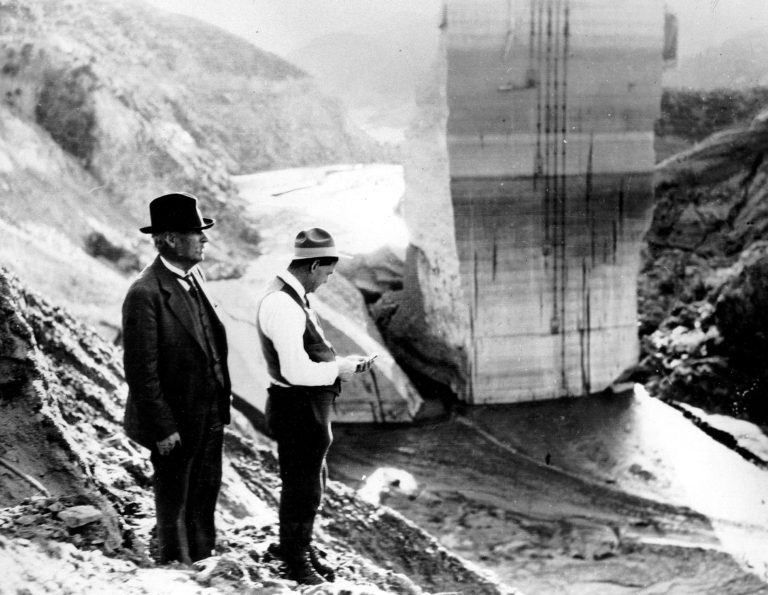

Also during his term as mayor, Eaton launched an extensive study of Southern California’s water supply and deduced that Owens River, fed by the annual snows of the lofty Eastern Sierra mountain range, would be the best future water source for Los Angeles. In 1904, Eaton and Mulholland inspected the Owens Valley firsthand, and Mulholland agreed that the plan was feasible.

A few immense hurdles stood in the way of achieving that goal. First, the Owens River Valley lay 250 miles to the north of Los Angeles, and the water would have to be conducted via a 233-mile aqueduct, tunnels, and siphons over two mountain ranges. Second, the land over which the aqueduct would pass was all privately owned. Third, the project cost was calculated at $23 million, an enormous sum that today would equal more than half a billion dollars.

Undaunted, the two men started working on their gargantuan task. Eaton, a land speculator and real estate developer at heart, began buying up property in the Owens Valley. He gave the impression that he was working on a public irrigation project for the U.S. Reclamation Service. Local residents were furious when they discovered he was buying land and water rights for Los Angeles. The tracts over which the aqueduct would actually run he eventually sold to the city for a pittance; the rest he planned to develop.

After securing the land and water rights, the Board of Water Commissioners needed to obtain funding from Los Angeles residents and legal rights from the federal government to construct the aqueduct. A bond measure to raise the needed construction funds was placed on the Los Angeles voting ballot and passed by a 10 to 1 margin. On June 25, 1906, after a heated debate among California Congressmen in the House of Representatives, President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law a congressional bill granting Los Angeles the rights to Owens River Valley water.

The actual construction of the aqueduct was left entirely to Mulholland, who was installed as Chief Engineer of the Bureau of Los Angeles Aqueduct. Five times, Mulholland personally traveled and inspected every piece of land purchased by the city and every foot of the proposed waterway’s route. Five times, he climbed the mountain peaks over which it would have to pass. After four years of surveying, planning, designing, fundraising, and political maneuvering, construction of the aqueduct began in 1908.

The most difficult part of the aqueduct’s construction was tunneling. There were 142 tunnels, totaling 43 miles in length, that had to be dug. The Elizabeth Tunnel was the longest, with a length of over five miles. In the first 11 months of work, 22 miles of tunnel were driven. The Elizabeth Tunnel set the world record for hard rock tunnel driving: 604 feet in one month. The Board of Engineers had estimated it would take five years to finish the five-mile tunnel. The task came in 20 months ahead of schedule.

Men came from all over the world to work on the aqueduct’s construction. Mulholland had hoped to use newly invented gasoline-powered tractors for the work, but the terrain proved too tough for the early machines. Instead, 52-mule team wagons transported mammoth 30-ton sections of steel pipe along sun-baked desert trails to the job sites.

Land covering 4,300 acres of limestone formations and clay deposits near the Mojave Desert was purchased, and a cement mill capable of producing the necessary millions of tons of cement was constructed. Two hydroelectric plants were built to provide electric power.

The aqueduct’s most challenging length was the completely gravity-powered 119,795-foot-long Jawbone Canyon Division, in which water is conveyed via pressure developed in the downslope to force the water through the upslope. The combination of canal, tunnel, and 15,000 tons of steel siphons and flumes begins at an elevation of 3,320 feet, descends 1,000 feet to the canyon floor, and rises to the 3,171-foot elevation of the opposite canyon wall. It took 15 months to construct and was completely designed by William Mulholland.

Building the aqueduct took five years, five thousand men, and six thousand mules. To Mulholland’s credit, the most difficult engineering project undertaken by any American was completed on schedule and within budget. The Los Angeles Aqueduct remains one of the modern world’s greatest engineering triumphs to this day.

On November 5, 1913 more than 30,000 Los Angeles residents attended a spectacular civic ceremony to view the first water from the Owens Valley complete its journey to Los Angeles. William Mulholland presided and called out for the water gate to be opened with one of the most famous and shortest speeches in Los Angeles history: “There it is, take it!”

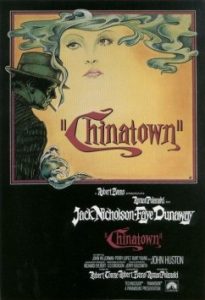

After the aqueduct’s opening, during the years that came to be known as the California Water Wars, irate residents of the Owens Valley campaigned against its effect on their environment and livelihoods. Farmers and ranchers protested that the water needed for their crops and herds was being diverted. Landholders across the valley complained that they had been swindled out of their property’s true value. At the height of the dispute, parts of the aqueduct system were sabotaged and dynamited. In 1974, Roman Polanski’s film noir classic “Chinatown” presented a riveting but highly fictionalized version of the political intrigue that brought water to Los Angeles and made Southern California urbanization possible.

The New York Times, in its review of “Chinatown,” wrote, “Whichever version of the history is correct — the scriptwriters of “Chinatown” certainly took sides — no one was more crucial to the outcome than William Mulholland, the Irish-born civil engineer whose vision of finding water for his adopted town was as inspired as his methods were ruthless.”

By 1923, the population influx to Los Angeles had exceeded even the most optimistic estimates. Foreseeing the need for yet another water supply source, Mulholland, then 68 years of age, personally initiated the Department of Water and Power’s six-year survey of 50,000 square miles of desert that resulted in the route ultimately selected for the Colorado River Aqueduct that now serves more than 130 communities in six Southern California counties.

William Mulholland had boundless confidence in the destiny of Los Angeles and its neighboring communities, but in 1928, his career took a tragic turn. On March 12th, the St. Francis Dam, one of several dams built to increase storage of Owens River water, collapsed, sending 12 billion gallons of water into the Santa Clara Valley, north of Los Angeles. The flood claimed more than 400 lives. The Coroner’s Jury investigating the failure found that the collapse was primarily caused by the ancient landslide material on which the eastern abutment of the dam was built. Mulholland was cleared of any charges since geologists of the 1920s could never have detected the instability of the rock formations.

Nevertheless, Mulholland took responsibility, saying: “If there is an error of human judgment, I am the human.” Several months later, he retired. His final years were lived in the shadow of the disaster.

William Mulholland remains a legendary and controversial figure in Southern California history. He has been called both a visionary and a villain for his key role in constructing the Los Angeles Aqueduct. However, no one can dispute that the Irish immigrants’ engineering triumph was pivotal in enabling the small Pueblo of Los Angeles to become one of America’s largest and most important cities.

Mulholland Tributes

William Mulholland was a self-educated man, but in 1914, the University of California at Berkeley bestowed on him an honorary doctorate degree. The inscription on the diploma read, “Percussit saxa et duxit flumina ad terram sitientum” (He broke the rocks and brought the river to the thirsty land).

Mulholland Drive & Highway

Mulholland Drive & Highway is a scenic road that runs 50 miles along the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains from the Hollywood Hills to the Pacific Ocean at the border of Los Angeles and Ventura Counties. Built during the 1920s “to take Angelenos from the city to the ocean,” it was dedicated in 1928 to honor William Mulholland, the man who enabled Los Angeles to become a major American city by securing a water source for the future. Multi-million-dollar homes lie all along its sinuous length. Breathtaking views of the San Fernando Valley can be seen from vantage points along its route. Mulholland Drive & Highway is one of the most famous roads in Los Angeles, equaled only by Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards, and a “must-do” drive for anyone wishing to grasp the immensity of the metropolis William Mulholland helped build.

The William Mulholland Memorial Fountain

William Mulholland, the Irish immigrant who worked as a ditch tender and lived in a one-room shack when he first arrived in Los Angeles, died in 1935. On August 1, 1940, a memorial fountain was dedicated in his honor, just steps from the shack where he began his pursuit of self-education to become an engineer.

The memorial’s simplistic design typifies the honest, straightforward character of the beloved man whom everyone simply called “Chief.” Gently cascading water jets at varying heights are illuminated at night in a full-color spectrum. A five-ton pink granite boulder symbolizing Mulholland’s rugged character stands at the memorial approach. It was brought down from the hills where Mulholland saw it while the Los Angeles Aqueduct was under construction and commented on its color. A memorial plaque on the boulder reads: “To William Mulholland (1855-1935): A Penniless Irish Immigrant Boy who Rose by the Force of his Industry, Intelligence, Integrity, and Intrepidity to be a Sturdy American Citizen, a Self-Educated Engineering Genius, a Whole-Hearted Humanitarian, the Father of this City’s Water System, and the Builder of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This Memorial is Gratefully Dedicated to those who are the Recipients of His Unselfish Bounty and the Beneficiaries of His Prophetic Vision.”

The Mulholland Fountain is located at the intersection of Riverside Drive and Los Feliz Blvd. In 1976, it was declared a Historic-Cultural Monument in the City of Los Angeles.

Photo: Craig Baker, Historical Marker Database.

Leave a Reply