The history of Limerick, Maine, in York County at the southwest corner of the state, is the history of the everyday: families having children; settlers clearing land, bartering for goods and services, building mills; farmers harvesting and selling at market. In this way, it is unremarkable; but it is also for this normalcy that Limerick today remains an unequivocally authentic New England town.

The 28 square miles over which incorporated Limerick spreads were former hunting grounds for the Abenaki Indians, an Algonquian-speaking tribe whose many sub-groups spread throughout New England. By the late 17th century, though, coastal settlements were expanding and one fur trader named Francis Small moved inland, allegedly purchasing what would become Limerick from the Abenaki for two blankets, two gallons of rum, two pounds of powder, four pounds of musket balls and twenty strings of beads, in 1668. Small then sold half his holding to Nicholas Shapleigh, a wealthy merchant, and although the land remained largely unsettled for the next hundred years due to the French and Indian Wars, the two families maintained the title.

In 1773, a decade after the French and Indian War ended with the Paris Treaty, a land dispute between Small and Shapleigh wound up in claims court. Though the specifics of the case may be lost, the result is known. The eminent York County lawyer James Sullivan won the case on behalf of the descendants of Small, while Shapleigh was granted the title of a small portion of the land he defended. This land he named after his father’s birthplace in Ireland, creating Limerick Plantation. A lead plaque unearthed in the 1850s and now housed at the Maine Historical Society, preserves the signatures of the original 14 settlers of Limerick Plantation, including James Sullivan. It is dated May 15, 1772.

Though James Sullivan never permanently settled in Limerick, he had a large hand in making it habitable. According to an 1859 biography written by his grandson Thomas Avery, in 1774, “He took his axe, week’s provision, and, in his blanket frock and trousers, went to Limerick with the other settlers, most of whom were from Saco, and commenced felling trees to reduce his land to a state of cultivation for the support of himself and his family. On Saturday he returned, the distance of thirty miles, black and cheerful as the natives when they return from a successful hunt.”

However much purchase this anecdote is given, it attests to the fact that Sullivan was a man of action. He was heavily involved in Massachusetts politics at the time (Maine was still then a part of Massachusetts and would not become a state until 1820) as an early advocate of the Constitutional Convention. He eventually served as one of the first justices on the Massachusetts Supreme Court, then as Attorney General for the Commonwealth, and was elected Governor of Massachusetts in 1807. One of his most famous cases while on the court was Commonwealth v. Nathaniel Jennison, which effectively abolished slavery in the state in 1783.

By 1787, the population of Limerick had grown to about 400 and the community was officially incorporated on March 6, 1787. Due to favorable soil conditions and its location near several water sources, Limerick thrived as an agricultural community. An account of the town written in 1830 by Charles Freeman paints an idyllic portrait of a typical New England farming town, where “nine-tenths of the inhabitants are employed in agriculture,” “a flock of sheep is owned in every farmer’s family,” and “orchards do well, and more cider is made than is for the interest of the town.”

Over the next century, the comment about sheep would be increasingly important, as the town gradually became a textile manufacturing hub. The town’s historic, and still operating, mill was built in 1846 by James Bradbury, who founded the Limerick Manufacturing Company. In 1857, it was purchased by Joshua Holland who became the supplier of wool blankets to the Union Army during the Civil War, now known as Holland Blankets. The company still exists today as Bosal Foam & Fiber, and since 1987 has been located at the same historic mill in which it began.

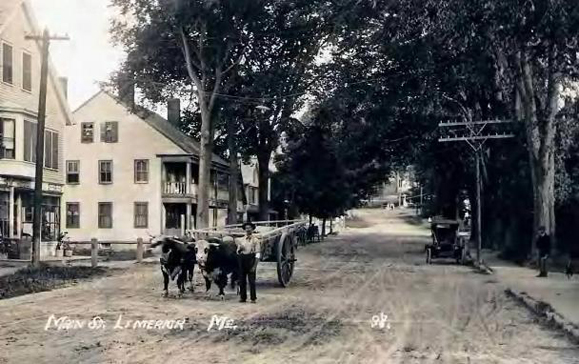

Since its founding, Limerick has had close relations with the larger cities of Maine like Saco, Biddeford, and Portland, though the direction of travel has changed. In the early days of settlement and development, Limerick agrarians and manufacturers would travel to town and sell goods like apples, cranberries, wheat, wool, and fabric. Now, however, the commute tends the other way, with urban residents visiting Limerick for its preserved heritage, thanks to the Limerick Historical Society, and easy access to hiking, fishing, hunting, snowmobiling, and cross-country skiing. Aislinn Sarnacki of the Bangor Daily News recommends a day hike up Limerick’s Sawyer Mountain, located in “the largest unfragmented block of undeveloped forested areas in York and Cumberland counties.” ♦

_______________

More from Irish America’s “Irish Place Names” series:

Leave a Reply