An excerpt from Seven Seconds, Holly Millea’s best-selling e-book in which celebrities and other luminaries share where they were and what they were doing when they found out JFK had been shot.

RYAN O’NEAL (22 years old):

I had a little baby in my arms and I was going to the unemployment office in my car – it was in the Valley in North Ridge. There were these small transistor radios that had just come out and people had them to their ears and everyone said, ‘He’s dead! He’s dead! They’ve shot the President!’ I was holding Tatum, it was just the two of us, and I had her in a carry thing, back then they didn’t even have straps. I was of draft age – 22 – and when Kennedy was made President in 1960, he made a rule that if you had a child, you were not the first to go to Vietnam. When my baby [Tatum] was born that moved me from A1 to A4. And three weeks later Kennedy was shot. Johnson took over and they revoked the rule, but I had already slipped through. Had I not, I’m sure I would have been sent off to Vietnam.

JULIAN FELLOWES (14 years old):

JULIAN FELLOWES (14 years old):

I was at school and I was at Appleforth College in Yorkshire, which is a Catholic boarding school. And I remember our lessons ended at 7:30 at night. And I had to walk up a hill because I was in a house called St. Bede’s at the top of quite a steep hill. So I was walking up the path with some other boys and suddenly we heard this shout, and a guy who was in my year called Richard Bradshaw suddenly ran towards us and said, ‘Kennedy’s been shot! Kennedy’s been shot!’

I remember that whole moment actually, though I suppose that is a testimony to the shock that we felt when we heard it. And remember, this was a Catholic school, and they were very, very keen on Jack Kennedy because there was a Catholic president of the United States, so clearly everything was now headed for the better. [Chuckles]. So they had an almost familiar connection with him, although of course they didn’t know him. But we used to pray for him and all that sort of thing.

There was this extraordinary, unbelievable shock that rippled up and down every corridor, and indeed the monks and the teachers as much as the boys—everyone was in a complete daze.

The next day I don’t think anyone did anything much. And then the rest of that term until Christmas was entirely dominated by his death. We were allowed to watch things on television that we normally weren’t and listen to the news on the radio. And of course we all rang our parents and they were shocked as well. So there was a sense of the whole country being in the grip of astonished horror.

There are only four public figures I can tell you exactly where I was hearing the news: Princess Grace, Marilyn Monroe, the Princess of Wales and Kennedy. I mean even Elvis, I can’t quite remember where I was when I heard the news Elvis was dead. And he, God knows, was a big enough figure in my youth.

Young death is the tragedy that resonates.

In those days during the Kennedy presidency, it was also just when the world was finally waking up after postwar austerity. Suddenly fashion and music and all sorts of things took a leap forward and somehow, Kennedy in the White House, who was young and healthy and handsome and looked as if he had the world on a string; and his wife who was beautiful and always wearing the latest fashions and setting trends more or less every time she opened her mouth, they seemed so glamorous a couple. They had more or less taken over from the Prince and Princess of Monaco, who had dominated those sorts of headlines at the end of the fifties. And they had become these icons, these gods. And the whole thing of Camelot, there was that musical Camelot. They seemed to represent a new Camelot that was governing America.

Looking across from rather war battered Europe, where rationing had only ended ten years before, here was this golden country across the sea with this golden couple ruling it. And I suppose we did sort of take them into our hearts. We loved them really.

JAMES PATTERSON: (16 years old)

JAMES PATTERSON: (16 years old)

It’s strange, as you get older, a lot of things fade. It’s interesting how a couple of things happen to you that don’t fade, they stay very much alive in your mind. You hope you recall them correctly.

I believe I was a sophomore in high school. And I believe we learned in class that the president had been shot. We had a big basketball game that night and that was immediately canceled.

This was a Catholic high school – St. Patrick’s High School in Newburg, New York – so I was taught by brothers. And the brothers didn’t show a lot of emotion, but the brother who came in was crying which was kind of unheard of. And then the high school, within an hour or so, they had a special mass. They called everyone over to chapel.

And I think for a lot of us it was kind of dreamlike, we were probably in shock a bit. And then in our house at least, TV was really rationed in those days – you might get to watch half an hour a day or something like that. That day and the next we were all glued to the television. I’m not sure this is accurate, but I think we actually saw Oswald get shot by Ruby live on TV when it happened. I’m not 100% on that. But I think we were watching when it happened.

In those days there were a lot of comfortable illusions that we lived under, you know, the Father Knows Best, Ozzie and Harriet, Leave it to Beaver… all that stuff. And I think, although we didn’t realize it then, it was kind of the beginning of the end of the age of innocence for a lot of us. Because then came the assassination of Dr. King, then Bobby Kennedy was shot, then Vietnam, then Watergate, which was kind of the nail in the coffin in terms of the way a lot of us felt about this country and our own sense of what reality was or wasn’t.

The fact that he was Catholic, it didn’t filter in people’s minds when he was shot, we didn’t think it had anything to do with him being Catholic. We liked the idea that whatever the bias had been about a Catholic, that that had been eliminated – that was a good thing, like any bias that’s eliminated. That was very positive for us.

But the attachment had at that stage of being shot, had less to do with the fact that it was a Catholic then just the fact that he was very charismatic and he was the first real television president. That’s probably one of the reasons that he won the election – and one of the reasons he got the nomination over LBJ. He was just so much better on television.

Seven Seconds

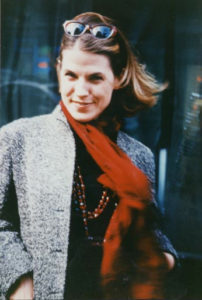

Holly Millea talks about her new book, a collection of memories of the JFK Assassination.

Holly Millea talks about her new book, a collection of memories of the JFK Assassination.

When did you start this project and why did you want to do it?

When I was interviewing Warren Beatty for Premiere in 2007, he recalled his early attraction to politics and John Kennedy being a big part of that. It was startling the way his answer to the obvious question so casually encompassed future icons – Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, producer Charlie Feldman. When my editor and friends asked how the interview went, the first thing I said was, “You’ll never guess who he was with and what he was doing when Kennedy was shot…” I realized that if that was my first response to “How was Warren Beatty?” I should keep asking that question.

What makes your book different from all the other books on Kennedy?

For starters, the personal memories of over 50 icons telling you about a tragic moment in their lives that, while universal, is inherently intimate. Beyond that, each of their experiences sheds a unique light on different aspects of the culture at the time – sex, religion, civil rights, music, fashion, politics…

What surprised you in terms of the stories you got from people?

I was only 2 when Kennedy was shot. As I grew, so did the Kennedy myth. I took it for granted that he was this beloved man and heroic figure – that’s all I’d ever heard because I was raised Catholic. So I was really surprised by some of the stories, like the great artist Chuck Close recalling a group of Republican law students at Yale “drinking a toast to the death of JFK.” Or director Paul Schrader’s memory of Kennedy being elected and his mother saying, “The first thing he will do as President is go to Rome and kiss the Pope’s ring,” and the way she wept when Kennedy was killed. There’s a lot of dark humor in some of the stories, which was really surprising. You have to read crime novelist James Ellroy’s recollection! It is dark and winding and visceral and I dare say entertaining.

Who was the most important person you interviewed?

Each is important in their own way because they touched on something different. Barbra Streisand’s story reminds us of how material things become immaterial in times of tragedy; Meryl Streep brings up the bomb; Liza Minnelli and Lorna Luft share stories of their mom Judy Garland’s friendship with Kennedy; playwright Tom Stoppard speaks so beautifully to our need for human connection.

But I must say having Nora Ephron in the book means the most to me personally. I’d interviewed her a lot over the years, and just loved her. Still do! It’s bittersweet to have her recollection of the way her day played out. It’s hilarious – total comedic chaos. And the way she tells it is pure Nora. I read it and hear her voice so clearly. What a gift!

Why, fifty years later, are we still fascinated with JFK and the Kennedy family?

The combination of beauty and wealth and tragedy has a lot to do with it. And the fact that many members of the family have turned their gaze and used their power to help the less fortunate. They are truly catholic Catholics. And then there’s the dream of what could have been – what the world would be like had JFK and Robert Kennedy lived. You can only imagine.

–––

Seven Seconds ebook [Byliner, $1.99] is available as a Kindle Single at Amazon; a Quick Read at Apple’s iBookstore; a Nook Snap at BarnesandNoble.com, and a Short Read at Kobo. The story is free to Byliner subscribers at Byliner.com.

Holly Millea is a longtime journalist and award-winning columnist for Elle magazine.

Click here to see Holly interviewed on the Huffington Post Live

And here to see her on MSNBC’s Jansing & Co. with Senator Patrick Leahy and the New Yorker’s Hendrick Herztberg

Such a shame to see so many still turning a buck from Kennedy’s murder fifty years later.

Martin, are you serious? I’m glad someone is getting these stories down while people old enough to remember are still here to tell them. I loved Nora Ephron’s movies and her book I Feel Bad About My Neck. And I loved reading her memoiry of that day. Unlike you, I’ve actually read this book and it’s GREAT.

I, for one think it’s great that someone has recorded this oral history — Kennedy’s assassination was one of the most significant events in American history. The memories of those interviewed would be lost to us if Millea hadn’t tracked them down and gotten them to talk to her. And at $1.99 she’s certainly not going to get rich off the venture.

I was 7, in Catholic School in a Virginia suburb of DC. A nun came into the class, whispered to our teacher, also a nun, who was quite strict, but was visibly shaken much to my surprise. She did the sign of the cross, and said, “Children, something has happened. Your parents will be meeting you, and you are dismissed.” Most of us walked to school, and I was met right outside of the schoolyard by my mom. I asked her why I was going home so early. She told me as we were walking. I remember looking down at the sidewalk, it was cold outside, and feeling positively horrible. I said, “Why would they do that?” My mom must’ve said something to the effect, “…the person is not good.” Kennedy, at that time for me, was my “crush.” He was young, happy and I was devastated that he was gone. That day, we were having wallpaper hung in my bedroom, pink ballerinas. The wallpaper guy told my mom that “…he hated Kennedy, and was glad he was gone.” Thankfully, I didn’t associate the ballerinas, from that day forward, with that tragic day. The day of the funeral, my dad decided, at the last minute, that we would drive to DC to see the caisson pass the gates to Arlington Cemetery. We got there just in time, stood in the crowd, and with all the hundreds of people, you could only hear the “clip clop” of the horses’ hooves on the pavement, carrying his body. I was up on my brother’s shoulders, and saw the black caisson go by, but really only remember the lonely sound of the horses’ hooves. Will never forget that. Never mind it was cold, I didn’t feel that. Only the horrible feeling that the world had changed forever.