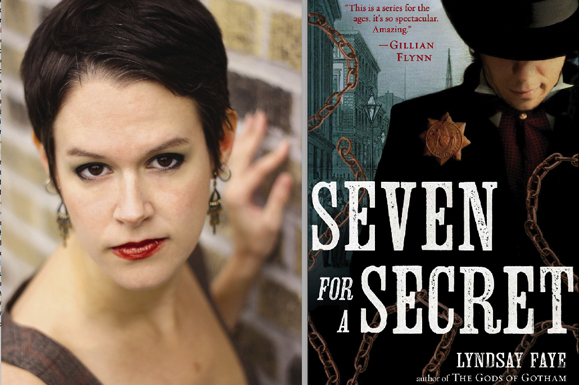

Lyndsay Faye’s Gods of Gotham series, about the earliest days of the New York City Police Department, has taken the literary world by storm. With a second book, Seven for a Secret, just released, Faye talks to Tom Deignan about her Irish roots, her acting past and her fascination with history.

“My great-great-grandmother was Irish,” says Lyndsay Faye, whose latest Famine-era historical thriller Seven For A Secret has just hit bookstores. This is the second book in a planned trilogy that explores New York City in the middle of the 19th -century, when the NYPD was created and thousands of destitute Irish were arriving each week.

Seven For A Secret has already earned praise, including starred reviews in Publisher’s Weekly and Book List. Best-selling author (Gone Girl) Gillian Flynn has called Faye’s books “a series for the ages. . . . Amazing.”

“Katie was her name,” says Faye, 33, of her great-great grandmother. “Her mother was widowed at a young age and she remarried a Pennsylvania Dutch German. Apparently this guy was a sociopath. He enforced a strict disciplinary code with a cat o’ nine tails whip. Katie was never allowed to go to school and did all the work around the farm.” Faye, who learned the story from her own grandmother, continued: “Katie married and had three children but her husband died. She was determined to give her children the education she never received, and supported the family by becoming an exceptional cook and pastry chef.”

Given that we are seated in a cozy coffee house, in the literary capital of the world discussing Faye’s just-released third novel, it’s tempting to see Katie’s adversity as yet another ultimately triumphant part of the Irish American dream. Later generations could perhaps track down Katie’s roots in Ireland and honor her sacrifice.

“There’s just one problem,” says Faye.“ We don’t know her last name. Her mother never told her anything but the German name. It bothers my grandmother to this day.”

Giving Names Back

History is filled with horrors — the Holocaust, American slavery, the Soviet gulag. For each of these horrors, a durable literary masterpiece has been produced by those who were there: Night by Elie Wiesel, Frederick Douglass’ memoirs, A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. However, the toll of the Great Hunger on those who fled Ireland was apparently so calamitous that those who lived through it were never to produce such an enduring work.

In recent years, a diverse array of authors have labored to fill this historical gap. Writers such as Peter Quinn and Kevin Baker, Peter Behrens and Joseph O’Connor have given names — and joy and sadness and love and rage — back to people like Katie.

We can now add Lyndsay Faye to this impressive list of novelists. Her first published book was 2009’s Dust and Shadow, in which she turned a life-long passion for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries into a brilliant mash-up, featuring the famed Baker Street detective trying to solve the infamous Jack the Ripper murders.

“I’ve been obsessed with Sherlock Holmes since I was 10,” says Faye, who shifts easily from serious literary analysis to ironic observation, sometimes while discussing the same subject, all before punctuating her point with a burst of laughter. (On the restrictions of marketing in publishing: “What would the cover of a Jane Austen novel look like today? It would be pink!”)

With her fashionably cropped dark hair and ready-for-stage appearance (somewhere between Rachel Maddow and actress Ally Sheedy), Faye does not fit the stereotype of someone who spends hours peering at microfilm copies of 19th-century New York newspapers. She does, however, look exactly like someone who would belong to an irreverent literary circle of Sherlock Holmes devotees called “The Baker Street Babes,” who produce a popular podcast and analyze all things Holmes, from A Study in Scarlet to the BBC series Sherlock.

In search of a follow-up to Dust and Shadow, Faye became fascinated by the glut of TV shows, movies and books that revolve around the NYPD. It led to the question: What was it like when the NYPD was actually created?

That is how “copper star” Timothy Wilde was born.

Holy War

We first met Wilde in Faye’s 2012 historical thriller The Gods of Gotham. He, along with his brother Valentine, are “copper stars,” the first police officers to patrol the mean streets of the Five Points and beyond in 1845, when New York City’s first municipal police force was created.

“People often ask me: ‘How did you come up with that?’ “Faye says, regarding the coincidental timing of the Famine and the creation of the police force. “And I say ‘I didn’t!’ That actually happened!”

Timothy (an orphan who is unsure of his own origins) was left horribly disfigured by a devastating fire in downtown Manhattan and spends much of The Gods of Gotham trying to track down a killer who may or may be motivated by the Catholic-Protestant holy war simmering on New York City’s streets.

Faye vividly recreates life in the harsh Irish wards, and even includes snippets of primary sources from the day, to convey the vehemence of anti-Irish sentiment in certain quarters.

Like the young police force to which he belongs, Timothy Wilde experiences growing pains, battling his own politically-connected (not to mention sexually and narcotically adventurous) brother and falling in love with the charitable daughter of a respected reverend, Mercy Underhill, who spends her days “tending to low Irish families, against all sense,” as one anti-immigrant character puts it.

Gods of Gotham earned high praise, particularly for Faye’s use of “flash patter,” a street language commonly practiced by thieves and believed to have originated in London. New York police chief (and recurring Faye character) George Washington Matsell even wrote a book called Vocabulum: Or The Rogue’s Lexicon, collecting underworld words and phrases such as “dead rabbit” and “kinchin.” (Interestingly, in his acclaimed book How the Irish Invented Slang, the late Daniel Cassidy argues that the flash patter collected by Matsell was actually popularized by 19th Century Irish writer Pierce Egan, and that since London’s slum districts were “overwhelmingly Irish” the “slang that emerged from its back streets and lanes was as Irish as Egan himself.”)

Sold Into Slavery

In Faye’s new book, Seven for a Secret, Timothy Wilde has learned from his experiences – somewhat.

“He’s not quite as hapless as he used to be,” Faye says, adding that Timothy is still an “unreliable” narrator – well intentioned, but naive and unable to read certain people well.

If religion was the central historical question in Gods of Gotham, it is race that is central to Seven for a Secret. Its fast-paced, multi-layered plot revolves around the revolting underworld of “blackbirders,” who kidnap free blacks in the North and sell them into the slave system still flourishing in the South in the 1840s.

Aside from allowing Faye to create a complex cast of characters who are good, bad, and somewhere in between, Seven for a Secret also probes the historical tensions between the Irish and African Americans, as well as the good, the bad, and the ugly aspects of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party, and even New York City’s complicity in the slave trade.

“I really wanted to highlight the resilience of the African American community,” says Faye, who notes that her latest book is coming out at roughly the same time as the film 12 Years a Slave, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and acclaimed Irish actor Michael Fassbender. The film (which is slated to open October 18) is based on the memoirs of Solomon Northrup, which Faye considered a “harrowing” yet “riveting” resource.

Meanwhile, BBC America’s show Copper is in its second season. It, too, explores the gritty life of a Five Points police officer, though the show is set a few years later, during the Civil War.

“A Zeitgeist Thing”

“When Copper first came out, I got a lot of Tweets about how I should get a lawyer,” Faye says with a laugh. But she isn’t claiming to have been ripped off. Instead, she calls this glut of quality historical stories “a zeitgeist thing,” which indicates there is a desire to understand crucial moments in American history.

“It’s an important task for us to remember where we came from,” says Faye.

An Actress First

Faye did not initially intend to become a writer. In fact, she was a successful theatrical performer for about a decade on the West Coast, but said the grind of auditioning – and the sheer level of acting talent out there – was daunting.

Like fellow actress-turned-mystery writer Tana French (whose books are set in Dublin, where she lives), Faye says acting was great training for novel writing.

“I knew how to write dialogue because I’d been on stage doing it for 10 years. It’s the best training in the world when it comes to character development,” she says.

In 2005, Faye, who says she is “about as ethnically American as you can get,” (aside from her Irish roots, she also has German and Native American ancestry, and is also a direct descendant of Mayflower passenger Jahn Alden), moved to New York with her husband Gabriel, a writer, performer and painter, to further her acting career.

When the restaurant she worked in closed, Faye began to examine the intense demands of acting and turned to writing, in search of more “autonomy” in her life.

“If you go to an audition room in New York, you’re going to see fifty of me in the hallway. But there aren’t fifty of me who could sit down and say: ‘I’m going to write a novel that is as close to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s voice as possible – since I am an actor – mixed with all of the elements of the Jack the Ripper killings,’” she says, referring to Dust and Shadow, her first novel.

Faye will spend September on an extensive cross-country book tour, which will include a final stop in Portland, Oregon, not too far from Washington, where she grew up.

“I’ve never done a signing where people from my high school could show up,” she says. “I’m excited about it.”

Faye also had a chance to visit Ireland for nearly a week while promoting Gods of Gotham.

“It was utterly beautiful and just as gorgeous as I always imagined it. All the Irish people we met were just as friendly and sharp and funny and warm as I always thought them to be.”

Currently, Faye is at work on the third installment of her trilogy, which will again follow Timothy Wilde, but will be set a few years later and explore the world of seamstresses and, more broadly, the role of women workers in the mid-19th Century.

Has Faye ever been tempted to transform her Irish great-great-grandmother’s life into fiction?

“I think her story has informed my writing and enriched what I was writing . . . [but] that’s part of my history.” Faye adds: “She’s real to me, so I don’t want to fictionalize that.”

No matter. In her fiction, Lyndsay Faye has managed to recreate the world inhabited by her great-great grandmother – and millions of other Irish Americans like her.

Leave a Reply