When it comes to goblins, ghosts, and ghoulies, most folk – without a fluttering heartbeat’s hesitation – will name Transylvania as the epicenter for scary creatures of the night. There’s hardly a soul that hasn’t shivered in fear while watching one of the many filmed scenes of a midnight visitation from that archetype of the undead Count Dracula, a chancy encounter with some sinister siren from the Count’s bevy of blood-lusting beauties, or a fatal full-moon face-off with a snarling fang-gnashing werewolf.

Few folk, however, realize that the author of literature’s ultimate tale of Transylvanian terror was, in fact, an Irishman named Bram Stoker, who was born November 8, 1847, in Clontarf, a coastal suburb of Dublin. Stoker was a victim of physical frailties that kept him bedridden for most of his childhood. His birthday fell in the shadow of Samhain, the Celtic year-end celebration when legends warned that all should wear disguises when traveling so as not to be whisked away by one of the malevolent spirits stalking the land. It is no wonder, then, that the best of Stoker’s tales spring from nightmarish themes.

The story of Count Dracula, though set in Transylvania, could as easily have been situated anywhere in Erin with Ireland’s own Dearg-due (Red Blood-Sucker) as its central character. Dracula’s seductive vampire companions, in fact, are most likely drawn from Waterford tales of a local female Dearg-due who rises from her coffin on certain nights to lure unsuspecting men into her arms and suck the lifeblood from their necks.

Though not so universally known as Dracula, three other of Stoker’s works treat matters filled with foreboding and fear. His rarely found first book of tales Under The Sunset (1881) recounts many of Ireland’s grisly myths. Though innocuous sounding, The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) is a tale about a vengeful mummy’s curse. In Stoker’s final opus, Lair of the White Worm (1911), the protagonist finds himself caught up in a horrifying web of inexplicably evil circumstances. (For those who would rather watch than read, the latter was filmed in 1988 by director Ken Russell. But I must tell you that the pace of reading is so much more exquisitely terrifying that once while reading Dracula, when a light suddenly switched off, I leaped and shrieked aloud!)

The list of creatures inhabiting forest, fen, hillock, and shore of the Emerald Isle is a veritable encyclopedia of the scary supernatural from which seanachies have drawn tales to chill the very marrow of listeners’ bones since time immemorial.

The majestic equine Phouka tosses unwary folk upon its back for a terrifying gallop across hill and dale. Fishermen ply their trade on ocean and lake ever mindful of the watery grave awaiting should they cross paths with the ravenous crocodilian Wurrum that measures more than fifty feet long and can swallow man and boat in one scaly lunge. Teine Sidhe, the fire fairies fond of darting about in peat bogs, lead those who would foolishly follow their flickering flames to a marshy grave. A 13th century poem entitled Wonders of Ireland, tells of the Laignech Faelad, men who under a full-moon can change into wolves and despite returning to human form have been spied with gobbets of raw flesh clamped in their bloody jaws. The Lanhuan Shee, or Fairy Mistress, casts a glamour on men with her dazzling beauty and draws off their life-force until they wither away and die. Dubhlachans, the headless drivers of the Death Coach, strike fear in the hearts of all with the sound of their snorting steeds and cracking whips as they rattle through towns to carry off the souls of the newly deceased. Even the pretty gossamer-gowned Daoine Sidh has the nasty habit of spiriting unwary mortals away from friends and families to live in the fairy mounds and dance jigs beneath the moon forever.

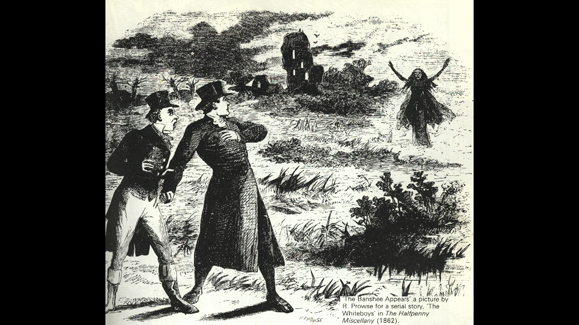

Of all the supernatural creatures found in Irish myth, none is more feared than the Bean Si (Banshee). Hearing her mournful wail is said to predict the death of a family member and seeing a Banshee foretells one’s own death. Perhaps the most unsettling trait of these spirits is that they can appear in the guise of a lovely lass, a maternal Machree (mother) figure, or an aged woman. Thus, you are well advised to be courteous to all women regardless of their age. Whether young, middle-aged, or elder, the Banshee always has long ashen hair that she untangles with a silver comb. She may wear a flowing dress of white, green, or black covered by a billowing grey cloak, or she may be wrapped in a linen grave shroud.

There is some basis for fact in the myth of the Banshee, as it was common at funerals for a woman to sing a caoineadh from which comes the modern word ‘keen’ meaning ‘to sing a sad lament.’ While most families’ keeners were mortal women, legend tells that five ancient bloodlines (the O’Gradys, O’Neills, O’Briens, O’Connors, and Kavanaghs) each had their own personal Bean Si who would appear to keen the funeral song. As time passed, however, these families widely intermarried and the Banshee’s wail, supposedly shrill enough to shatter glass, became feared by folk throughout the land.

Lastly, there is the Tash – the Irish ghost. From ruined castle and stately manor house to busy thoroughfares and remote country lanes, Ireland overflows with stories of ghosts, phantoms, specters, and wraiths that can appear as humans, dogs, cats, horses, birds, rabbits, or even butterflies. Most Tash are believed to be the spirits of people who died violently and are bound on the mortal plane to haunt their place of death as a lesson to others.

Not all of Ireland’s ghosts are mean-spirited. Once when staying in a lovely manor home in Wexford, I switched rooms the second night because a group of Ralph Lauren male models had booked in during a location shoot for the fashion mogul’s upcoming Fall line. At breakfast the following morning one of the fellows mentioned that his sleep had been interrupted by what sounded like someone entering his room, and when he opened his eyes, he swore he saw a man standing at the foot of his bed. At hearing this, the Lady of the house exclaimed: “How strange, the Captain usually only visits women!” Evidently the roguish Captain had come looking for me!

Why we humans enjoy being scared out of our wits is a mystery no one can explain, but since ancient days, autumn with its death of all green-growing things has been the chief time to do so, especially on Samhain and on All Hallow’s Eve, which both fall on 10/31 in 2013. Witness the roster of horror movies that Hollywood releases each October.

This year, how about doing something really scary? Ask some friends over for a night of spooky Irish storytelling guaranteed to send shivers up the staunchest spines. Set the scene with copious flickering candles. Costumes optional but advised, so that spirits stalking the streets won’t recognize you. Tasty food and drink a must to quell the hunger and quench the thirst of the seanachies. And don’t forget to leave a plate of Soul Cakes at the door. You might even be visited by one of the wandering goblins, ghosts, and ghoulies.

Sláinte!

SOUL CAKES (Personal Recipe)

1 3⁄4 cups oatmeal flakes

1⁄4 teaspoon baking powder

1⁄2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon melted butter

8 tablespoons hot water

Preheat oven to 350F. Pulverize 1 cup oatmeal in a blender. In a small bowl, combine ground oats, baking powder and salt. Stir in butter. Gradually add water to make a thick dough. Gather into a ball, place on a board lightly sprinkled with 1/4 cup oatmeal and roll around until completely covered with oat flakes. Spread another 1/4 cup of oatmeal on the board and roll the ball to 1/4 inch thick. Cut into 2-inch circles (I use a whiskey glass). Transfer circles to a pan sprinkled with the remaining oat flakes. Bake 10-15 minutes or barely brown. Remove from oven and dry on wire racks. Makes approx 3 dozen.

[Serve with a crock of Port-Cheddar Cheese that looks like it’s streaked with blood.]

NOTE: You may want to double or triple this recipe as Soul Cakes appeal to humans as well as wandering ghosts.

Leave a Reply