An exhibition on the Civil War, featuring photographs by Mathew Brady, Timothy O’Sullivan and others, and a new biography of Brady, are reviewed by Tom Deignan.

One of the most chilling portraits in the exhibition “Photography and the American Civil War” – which just finished a five-month run at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art – is also one of the most seemingly banal.

The mustachioed fellow in the photo is striking, with a full head of black hair, and a spotted neck tie. His hand fashionably rests inside his lapel. The picture is credited to photographic pioneer – and son of Irish immigrants – Mathew Brady.

In an exhibition that features gruesome photos of the dead at Gettysburg, as well as slaves scarred by abusive masters, it’s hard to see how this portrait of a dashing young man could carry any emotional impact whatsoever.

That is, until you see the fellow’s name: John Wilkes Booth.

The photo was taken before the acclaimed Shakespearean actor assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in the final days of the war. The casual nature of the photo makes the actions of Booth and his co-conspirators seem all the more chilling.

More broadly, thanks to Brady and his team of photographers – including Irish immigrant Timothy O’Sullivan and Scottish immigrant Alexander Gardner – we are able to better comprehend the full horror of the Civil War.

The exhibition examines the important, if generally misunderstood, role played by Brady in conceiving the first extended photographic coverage of any war. It also addresses the widely held, but inaccurate belief that Brady produced most of the surviving Civil War images. Although he actually made a few field photographs during the conflict, he commissioned and published, under his own name and imprint, negatives made by an ever-expanding team of field operators, chief among them being Gardner and O’Sullivan.

The curators also acknowledge that many of the more famous photos Brady and his team took were staged. (A writer for The Wall Street Journal wondered “how much of Brady’s wartime product – and how much of the output of his fellow photographers – presents an honest view of the brutal strife and how much instead is tendentious fabrication.”) But, I for one, found it impossible not to be moved by the images in this collection. The battlefield dead and the shocking portraits of the maimed and injured garner the most attention, but there are also poetic landscape shots, made all the more evocative by the knowledge that they were the sites of some of the bloodiest battles.

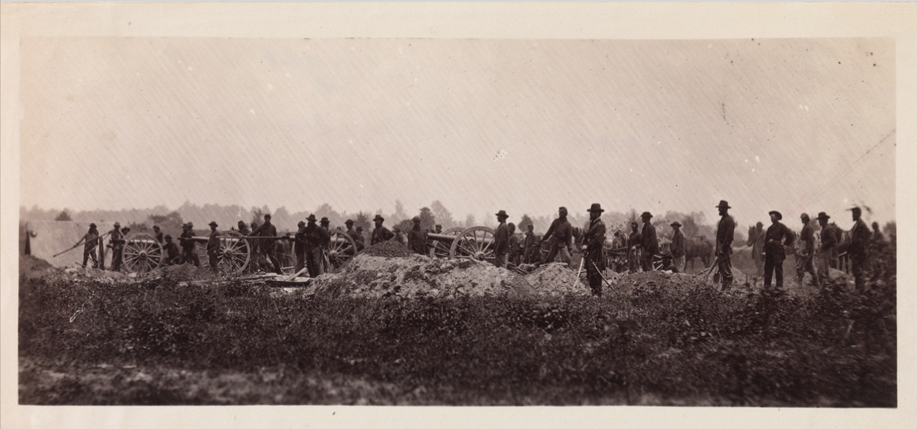

Constrained as they were by the limits of the equipment and the long exposure time that it took to properly transpose these images onto the glass negatives typically used in the field, these early war photographers were most effective when chronicling things that did not move – ruins, dead bodies, tents – which makes one photograph by O’Sullivan all the more interesting.

Titled “Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery B, Petersburg, Virginia,” O’Sullivan attempts the extraordinary for that period – an action shot. “Whether or not Company B were truly under fire or just drilling is moot,” the exhibit’s caption writer notes correctly.

The exhibition also shows how these early photographs made by Brady and company changed the way news was reported and distributed. The first broadside illustrated with a photograph appeared following Lincoln’s assassination. This was a photograph of Booth tipped onto a sheet and posted around the country with news of the atrocity and the $100,000 reward offered for the capture of Booth and his accomplices.

As well as being central to the exhibition, Brady is also the subject of a new biography by Robert Wilson.

In Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, Wilson explains that information about Brady’s youth and Irish roots are scarce, in part because “Brady himself was never much help on his origins,” but he does attest that “Brady was born around 1823 to an Irish immigrant named Andrew Brady and his wife, Julia, in Warren County, New York.”

Ironically, this pioneer of visual imagery developed a severe eye ailment as a child and was left nearly blind. “I met a Dr. Hinckley, who restored my sight, though my eyes were never very strong,” Brady later recalled. The poor eyesight is likely one reason Brady wrote so few letters and seemed to keep no journals, thus making details of his early life difficult to assemble.

Wilson does describe an important moment in Brady’s life when, in the late 1830s, he met up with Samuel F. B. Morse. Though best known as the inventor of the telegraph, Morse was also dabbling in daguerrotypes, the forerunner to photography. Brady would later credit Morse for helping him learn, then perfect, this new technology, which had only been invented in 1837. Ironically, Morse was not only a technological whiz but also, as Wilson notes, a fierce opponent of immigrants, especially Irish Catholics (he even ran for mayor in 1836 as a nativist party candidate). Perhaps Brady’s unwillingness to talk about his early life had to do with the anti-Irish bias prevalent at that time. Would Morse have helped him if he knew Brady’s background?

By 1844, Brady had his own daguerrotype studio in Manhattan, dedicated to creating portraits. According to Wilson, Brady was able to persuade prominent members of mid-19th century American society to sit for portraits because he was so charming, and skilled at cultivating friendships with the bold-faced names of his day.

Thus, when the Civil War broke out, Brady was well-positioned to visually record some of the most important moments in American history – photos that retain their power to this day, as evidence in many of the beautiful and harrowing images collected in “Photography and the American Civil War.”

Life after the Civil War, for Brady, was not so kind. His fortunes – and health – declined steadily, and he was living in near poverty when he died in 1894. He is buried, next to his wife, in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

“Photography and the American Civil War” runs at the Gibbes Museum in Charleston, South Carolina from September 27, 2013 to January 5, 2014 and at The New Orleans Museum of Art from January 31 to May 4, 2014.

Leave a Reply